Evaluation of M-Health On Medication Adherence In Tuberculosis Patients: A Systematic Review

Rd. Mustopa1*, Damris2, Syamsurizal2, M. Dwi Wiwik Emawati2

1Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Health Polytechnic of Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

2Doctoral Study Program, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Jambi University, Jambi, Indonesia

Corresponding author. Rd. Mustopa, JL. Haji Agus Salim Nomor 09 Kota Baru – Jambi 36361, Indonesia.

Orcid : https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6407-1452.

Phone: +62 821-9668-7959

Email: rdmustopa979@gmail.com

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Background & Aim: The success of the TB control program is closely related to patient adherence to treatment. Previous studies have provided many views regarding the use of variants of mHealth on TB patient adherence, but the results still need to be clarified. This review aims to evaluate and provide an overview of mHealth RCTs on medication adherence in the patient with tuberculosis.

Methods & Materials: The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guideline was followed to report study findings. A literature search for studies in the period of 2018-2022 in PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL and Sciencedirect databases was conducted. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that analyzed the effect of mHealth on medication adherence outcomes (treatment completion, treatment adherence, missed doses, and non-completed rate) were included. Adult patients with either active or latent TB infection were included. The Cochrane ’Risk of bias’ assessment tool was used to assess the risk of bias of eligible studies.

Result: Overall, searches on databases generated 2,607 articles, and only 18 articles met the criteria. Two authors independently screened and extracted data from eligible studies. There are two devices used in mHealth in the last five years: software (SMS, We chat, and Whatsapp) and hardware (MERM, eDOT, WOT). Based on descriptive analysis, the hardware mHealth is superior to the software mHealth. Close monitoring and measurement of the use of DOT hardware demonstrates the accuracy of treatment success.

Conclusion: It was found that mHealth interventions can be an advantageous approach. However, the interventions showed variable effects regarding the direction of effect and the rate of improvement of TB treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; eHealth; digital health; Adherence; digital adherence.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis is a disease that requires the sufferer’s adherence to a standardized treatment program to completely get rid of Mycobacterium, which is the main cause of this disease, from the sufferer’s body [1–3]. A total of 1.6 million people died from TB in 2021 (including 187,000 people living with HIV). Worldwide, TB is the 13th leading cause of death and the second infectious killer after COVID-19 (above HIV/AIDS). TB is a treatable and curable disease. Drug-susceptible TB disease is treated with a standard 4-month or 6-month course of 4 antimicrobial drugs (isoniazid and rifampicin) that are provided with support to the patient by a health worker or trained treatment supporter [4]. The high number of TB cases worldwide is part of patient non-adherence with treatment programs, which allows for an increase in new TB cases [5]. Non-adherence of TB patients to treatment can be seen from the large number of TB patients who are resistant to standard therapy or what is known as Drug Resistant-Tuberculosis (DR-TB). There are 157,903 Drug Resistant-Tuberculosis (DR-TB) cases in 2020 [6]. To overcome this situation, since 1995 WHO has introduced the DOTs (Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course) strategy. The study states that knowledge is the biggest variable in this aspect of non-adherence, without neglecting other variables such as attitudes and behaviour of TB patients [7]. For this reason, the focus of TB control should be on increasing compliance and changing patient behaviour [8].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided a good strategy for managing TB, primarily targeting patient compliance, which has long been known as Directly Observed Treatment (DOT). The strategy consisted of standard treatment using Rifampicin for six months for new cases and eight months for repeat cases [9]. These repeat cases were patients who had dropped out of treatment or failed to undergo previous treatment [10,11]. So, the DOT strategy and program are fine. This strategy requires a better approach and is adapted to the conditions of society. The limitations of the officers who will run this program should be a consideration for the birth of innovations to find which approach is better to do to significantly improve and change the compliance and behaviour of TB patients [12,13]. The birth of a very progressive digital technology that began in the 20th century can be the main choice in solving the problem of treating tuberculosis in the community through innovations in delivering pre-existing programs [14]. In several decades, studies on the use of digital technology to improve TB patient adherence and behaviour have increased sharply in various parts of the world.

The term commonly known today for using mobile devices to support public health care and practice is ‘mHealth, as introduced by WHO. mHealth also includes all mobile devices that use wireless or Bluetooth technology [9]. mHealth is particularly suitable for adherence interventions, as it involves using devices such as smartphones, Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs), tablets and many others [15–18]. These devices support several media, such as Short Messaging Services (SMS) or text messaging, voice or video calls, and specialized software applications (Apps) [15]. Previous studies involving mHealth included Liu and his team, who used a telephone reminder system to increase TB patient compliance [11]. In addition, there are studies using media SMS to serve as reminders for TB patients with good results [19–21].

Based on our initial search of the available studies, the results still need to be clarified. There are no results that show the certainty of the effectiveness of mHealth used. In addition, most of the studies over the five years showed that mHealth variations were similar. Likewise, previous review studies evaluate a lot from just one mHealth variant. To that end, the current review aims to evaluate and provide an overview of mHealth RCTs on medication adherence in the patient with tuberculosis.

METHODS

Design

This review was compiled based on the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic-review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [22].

Eligibility Criteria

This review was restricted to studies published in English, and included studies published through 2018 to 2023. Study types were limited to RCTs. In this review, an intervention for adherence and behaviour were defined as any strategy (e.g., self-management for diseases, and medication reminder) to change or maintain patient’s adherence and behaviour to improve health. We included studies on interventions that used mobile devices (wireless and portable electronics including cellular phones, wearable devices, laptop, personal assistance devices, and tablet PC) or mobile technologies (any technologies that enable communication with remote areas, such as phone call, video call, short messaging service [SMS], multimedia messaging service, online-chat, and email) to promote medication adherence. Observational study, non-intervention study, case report, study protocol, and commentary were excluded in this review.

Information Source

A literature search was performed on several reputable databases, such as PubMed, Sciencedirect, CINAHL, and Cochrane. The search was carried out in the period November 2022 to January 2023.

Search Strategy

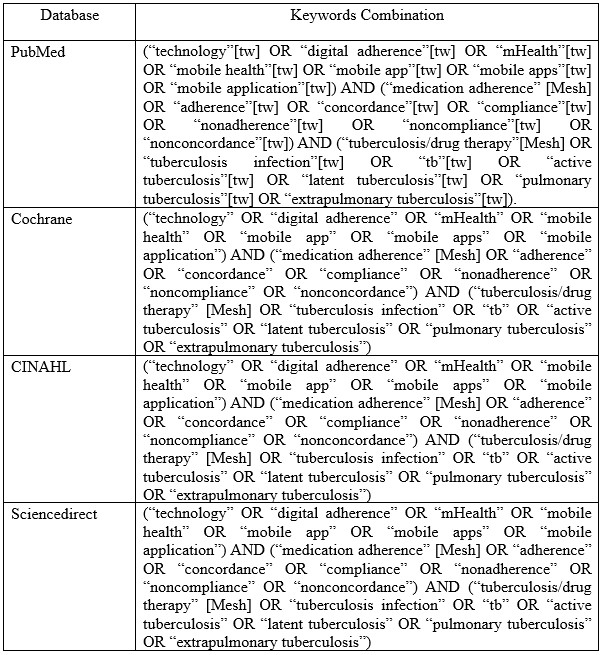

The keyword structure was compiled based on study population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and design were developed for the specific databases used. The search strategies for each database provided in the search string table (Table 1).

Selection Process

Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts from the collected literature. Then read the entire text of each article to assess its eligibility based on predetermined inclusion criteria. Discrepancies that arise are resolved through discussion, even if it is possible to ask for the consideration of the first author. The selection process is described in detail in the PRISMA diagram.

Table 1. Search string in databases

Data Extraction

DM and SR conducted eligibility evaluation based on the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and assessed by DM, SR and MD conducted further independent verification of the abstract and full-text screening. Any disagreements among the reviewers were resolved by discussion. Data from the selected articles were extracted by DM, SR, MD and then verified by RM for relevant information, such as publication year, type of mHealth intervention, setting, population, main findings, and control groups.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assess the risk of bias of each included trial using the Cochrane ’Risk of bias’ assessment tool, and discuss any differences of opinion (Higgins et al., 2011). In the case of missing or unclear information, we will contact the trial authors for clarification. The Cochrane approach assesses risk of bias across six domains: sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other potential biases. For each domain we will record the methods used by the trial authors to reduce the risk of bias and assign a judgment of either ’low’, ’high’, or ’unclear’ risk of bias.

RESULTS

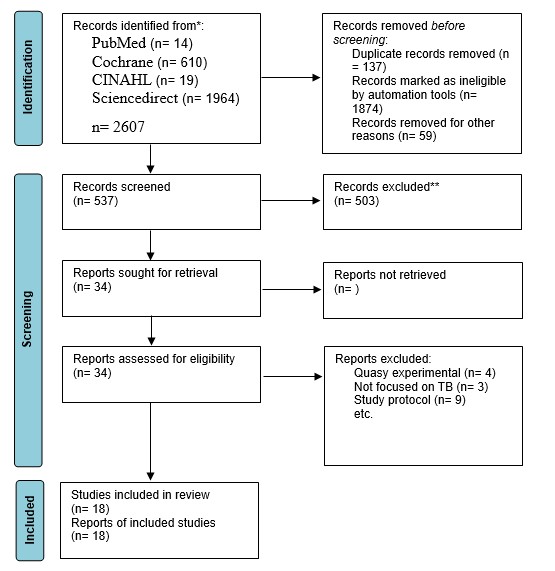

Overall search on databases resulted in a total of 2,607 articles. After removing 2070 articles for duplication, ineligibility and other reasons, 537 articles were left ready for screening. In the end, 18 articles were declared eligible to be included in this review study after removing 16 articles for reasons including not being an RCT study, not being focused on TB, and being a protocol study.

In full regarding the process of searching for articles can be seen in figure 1, while, in table 2 we reported the characteristics of the articles included in our study

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the studies selection

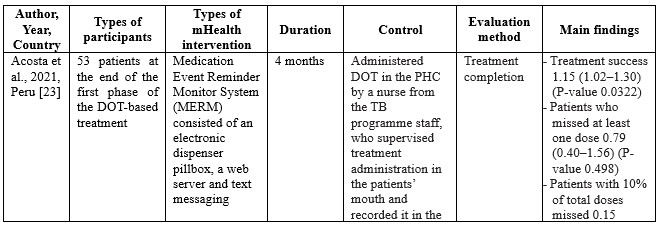

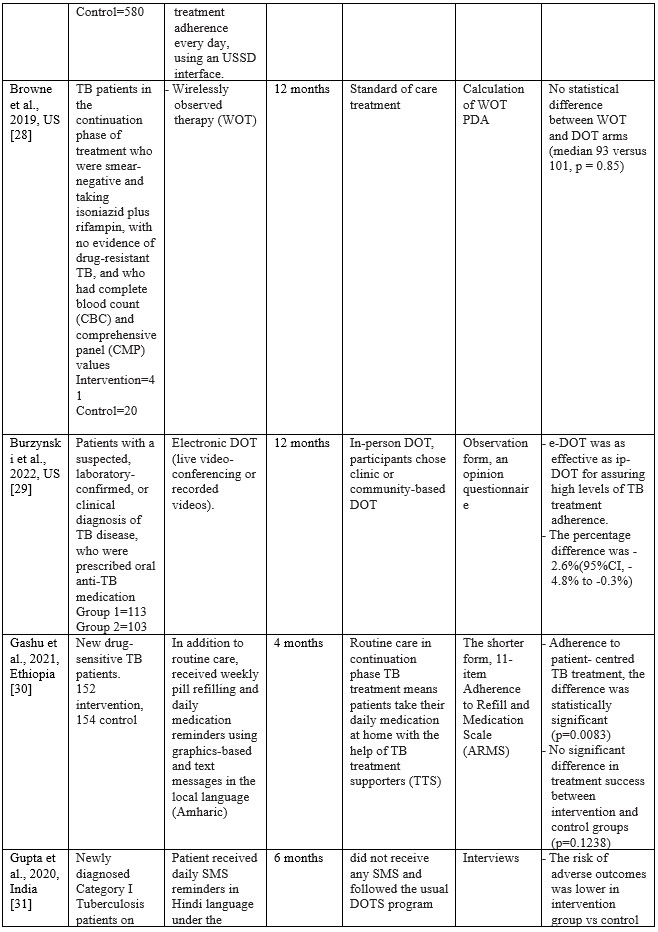

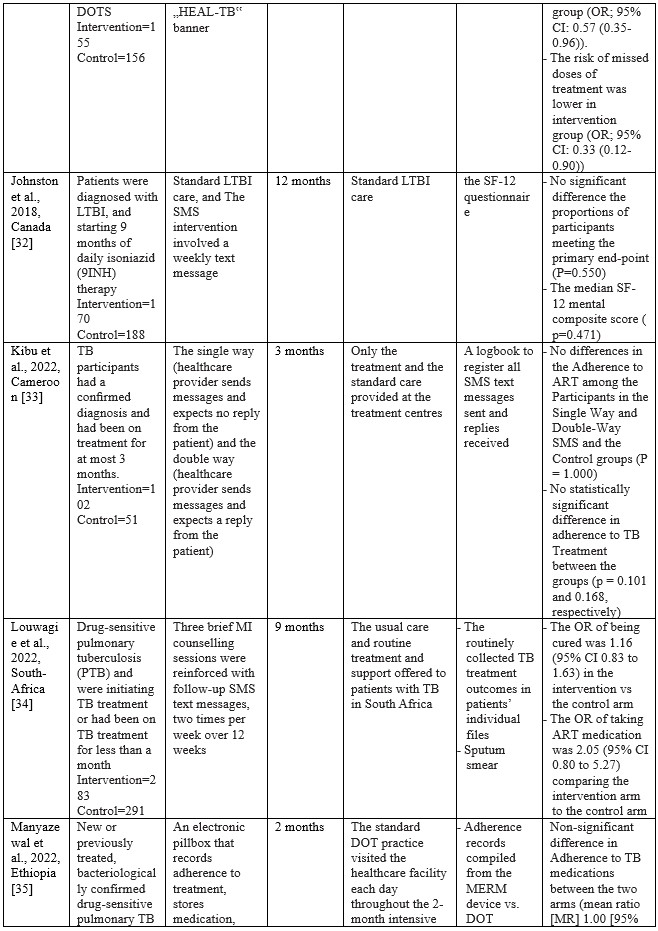

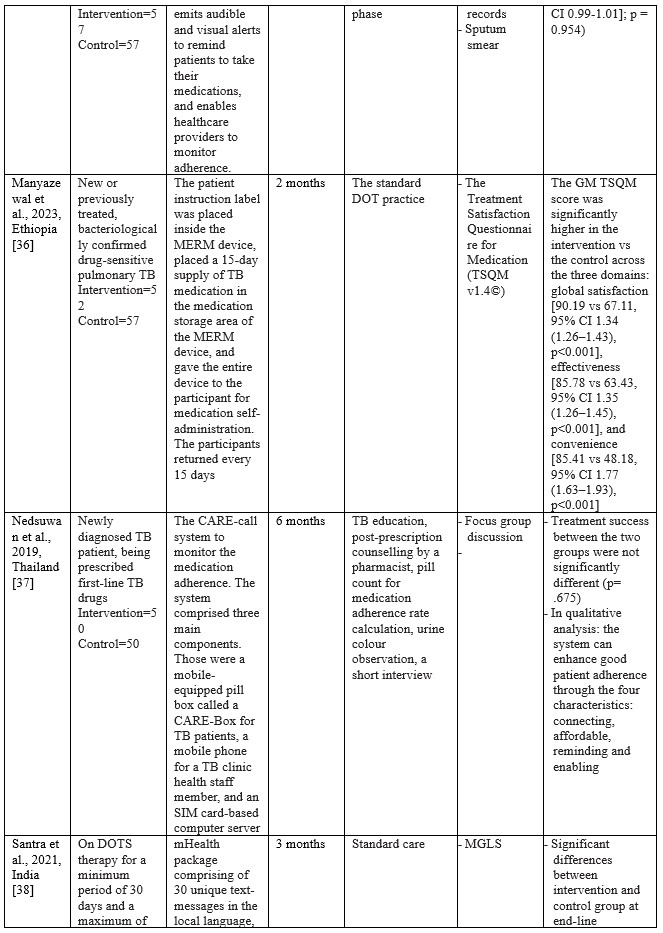

Table 2. Characteristics of Studies Included

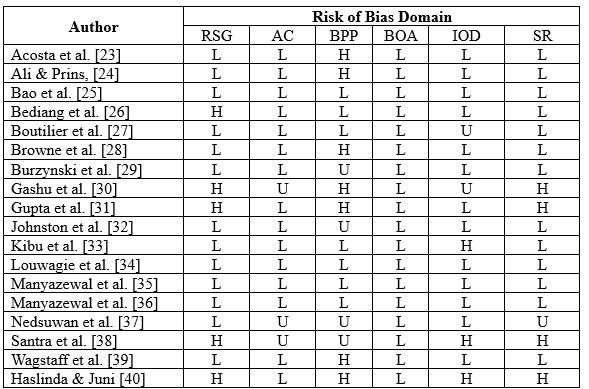

Summary of Risk of Bias assessment

The risk of bias in eligible studies using The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool resulted in the conclusion that there were four studies with a high risk of bias and one unclear.

*RSG= Random sequence generation, AC= Allocation Concealment, BPP= Blinding Of Participants and Personnel, BOA= Blinding of Outcome assessment, IOD= Incomplete Outcome Data, SR= Selective Reporting; H= High risk of bias; U= Unclear risk of bias; L= Low risk of bias.

Characteristics of eligible studies

Studies on using m-health applications as innovations to improve adherence, change behaviour, and the success of TB treatment in the last decade have shown a significant increase. We have collected 18 RCT studies from several countries, including Ethiopia (n=3), South Africa (n=2), India (n=2), Cameroon (n=2), US (n=2), and one study each in Thailand, Peru, Sudan, China, Kenya, Canada, and Malaysia. The number of TB patients included in the study ranged from 61 to 1,189, ranging from 18 to 60 years. Most of the studies involved participants newly diagnosed with TB based on positive bacteriology, On DOTS therapy, smears, negative pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), being prescribed first-line TB drugs, and drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB). The shortest duration of intervention given was two months, and the longest was 12 months.

m-Health intervention used

Based on the collected studies, the applications used include Short Messages Service (SMS), Medication Event Reminder Monitor System (MERM), WeChat groups, USSD interface, Wirelessly observed therapy (WOT), Digital Adherence Technologies (DATs), Electronic DOT (live video-conferencing or recorded videos), The CARE-call system, and TB@Clicks (Whatsapp).

Several m-Health collected from eligible studies can be broadly grouped into software and hardware applications. In general, m-health applications that use software provide information as reminders and TB education in writing or pictures. Through the SMS route, various interventions are carried out, starting every day, every two days, twice a week, and every week [24,26,27,31–34,38,39]. Through the We-Chat application, there is no time limit for interactions between patients and supervisors taking medication; at any time, patients can discuss all obstacles and questions with supervisors and fellow patients [25]. As for the Whatsapp application, studies report that in the intensive phase, reminders are given to patients every day and 1 to 3 months after the intervention package is carried out [40]. Through telephone calls, patients are also reminded and controlled by supervisors. The duration of each phone call is 10 minutes [24,38].

The hardware used in the intervention includes the Medication Event Reminder Monitor System (MERM), which is a pillbox dispenser that will sound an alarm at the set time to take medicine [23,35,36]. This model is similar to another system called CARE box; it is just that, in this system, when the lid of the box is opened, it will automatically make a missed call to the server [37]. Another device is Wirelessly Observed Therapy (WOT), a sensory device that enters the body to record what the patient consumes, including TB drugs. The data stored on the sensor is linked to a mobile device as information material for supervisors [28]. For E-DOT, a camera device records real-time video of the patient’s medication-taking activities; this system is also used to conduct video conferencing between supervisors and patients [29].

Effects of m-Health on TB patient adherence

In summary, m-Health, with its various variants, has a positive effect in that patients experience increased adherence and changes in behaviour, even though this is not stated explicitly. Several studies have found a positive effect on treatment success related to patient adherence, with P values of 0.0322 [23,24], 0.88 [26], 0.001 [27], 0.85 [28], 0.1238 [30], 0.782 [31], 0.550 [32], 0.101 [33], 0.443 [34], 0.954 [35], 0.001 [36], 0.675 [37], 0.005 [38], 0.03 [40]. Meanwhile, changes in patient behaviour can be seen in findings such as increased self-management behaviour with a P value <0.001 [25], lower risk of missed doses [31], taking ART medication with an OR value 2.05 [34], return to the clinic with a P value of 0.001 [39].

Comparisons between the intervention and control groups in all studies showed no significant differences. However, the intervention using the m-Health variant showed superiority compared to the control group, most of which were in the main form of standard care, Directly Observation Treatment (DOT).

Using MERM, TB patient adherence to treatment is higher than the DOT standard, where TB patients are 1.15 times more compliant when intervened with MERM than the DOT standard [23]. The patients in the SMS intervention group had a lower failure rate (6.8%; 5 of 74 patients) compared to the control group (10.8%; 8 of 74 patients) [24]. In a study conducted by Bediang and colleagues using m-Health in the form of SMS, treatment success was higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (111 patients: 106 patients) [26]. Using SMS messages daily and an unstructured supplementary services data (USSD) interface shows that the probability of unsuccessful treatment outcomes for individuals in the intervention group is approximately 0.08 less than for individuals in the control group [41]. Browne and colleagues found that WOT was superior to DOT in supporting confirmed daily adherence to TB medications, where (3,738 out of 4,022) prescribed doses were confirmed in the WOT treatment, significantly different (p < 0.001) from the 63.1% (1,202 out) of 1,904) of prescribed doses observed in the DOT arm [28]. One hundred seventy-three patients completed the treatment program through the DOT electronic intervention [29]. One hundred ten patients out of a total of 139 TB patients adhered to treatment after intervention using a Mobile phone-based weekly refilling with a daily medication reminder system [30]. Gupta and colleagues found that the treatment success rates in the intervention group using SMS reminders were 86.4%, and the control group was 76.2% [42]. Louwagie and colleagues found that after six months of text SMS intervention, 120 of 133 patients adhered to the TB treatment given [34]. Manyazewal and colleagues using MERM found seven patients completed treatment compared to the control group of 5 [35]. Nedsuwan and colleagues found that using the mobile-based CARE-call system, the number of non-adherence patients in the intervention group was significantly lower than that of the control group (7.5% vs. 27.5%) [37]. Santra and colleagues found that the proportion of participants adherent to DOTS in the intervention group using phone calls and text messages increased from 85.5% at baseline to 96.4% at endline, postintervention [38]. Wagstaff and colleagues found that using SMS messages, as many as 62.0% of patients returned to the clinic in two days compared to 51.5% in the control group [39]. Using the Whatsapp message intervention, Haslinda and Juni found that the number of respondents who adhered to medication was higher in the group that received the intervention (81.8%) compared to the control group (69.1%) [40].

DISCUSSION

This systematic review study aims to evaluate and provide an overview of mHealth RCTs on medication adherence in the patient with tuberculosis which we have successfully conducted by collecting eighteen eligible studies from 2018 to 2022. One of the reasons we limited our literature search to the last five years was to see application innovations that were used along with the development of the digital world in this period. The expectancy is that the latest technological advances in this digitalization era will make it more straightforward to develop information innovations, especially concerning the health sector, to educate patients and the public.

Since the emergence of digital devices, health practitioners are increasingly competing to take advantage of this progress as a good opportunity to help improve public health in preventive and curative ways. M-Health has been attracting attention since it emerged as an innovation that effectively streamlines interactions between healthcare workers and patients, especially in supervising patients such as TB with strict rules for taking drugs for a certain duration. With a relatively lower cost, m-Health can be the first choice in addition to existing programs for monitoring TB patients. For this reason, this study provides an overview of the effectiveness of the m-Health variant from RCT studies in the 2018 to 2022 period regarding adherence and behaviour changes in TB sufferers during the treatment period. The m-Health variants used in the study are software and hardware. This review study analyzed m-Health variants that were not discussed in several previous systematic reviews [43–46].

The m-Health used in the last Five years

Until the last five years, SMS is still an option to remind TB patients to take their medicine. In contrast to previous review studies [45,46], the effectiveness of SMS in monitoring the treatment of TB patients in this review showed no significant difference between the SMS intervention group and the control group with standard care using DOT. Even using the Whatsapp application, TB patient compliance did not show any significance, even though adherence to treatment in the intervention group was higher than the control group [40]. However, with the widespread use of cellphones with the Android system or iPhone Operating System (iOS) among the public, choosing intervention using SMS or chat remains the best choice considering the low cost and efficient application. In contrast to the findings of Bao and colleagues in China, the We-Chat application used as an intervention showed a significant increase in adherence and repeat visits to the clinic during a TB treatment program [25]. Besides the effectiveness of existing smartphone-based applications, various obstacles can be faced, especially for populations in remote areas, where cellular networks and even the internet may be inadequate, especially if the quality of the patient’s cell phone does not support the use of these applications [47].

Behaviours expected of TB sufferers include not spitting, covering the nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing, and wearing a mask [48]. Of course, TB sufferers expect this behaviour to be carried out as one of the steps to prevent the spread of the disease in the surrounding environment [49]. However, the family should be involved in education on the prevention and care of TB patients. The family has an important role in the patient’s treatment process, including preventing the spread of the disease so that it does not affect the people who live in the same house and the people around the house. Families can provide arrangements at home according to good health standards, especially for TB patients. For this reason, further studies need to analyze this educational intervention for families with TB sufferers.

Some of the studies included in this review also provide interventions using a variety of hardware such as the Medication Event Reminder Monitor System (MERM), CARE box, Wirelessly Observed Therapy (WOT), and Electronic-Directly Observation Treatment (E-DOT). These devices are under recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) to increase the adherence of TB patients undergoing six months of treatment [14]. Of the six studies that implemented these hardware devices, overall, they showed better success than using software on TB patient adherence to taking medication. The MERM system allows TB patients to take medication daily because the device cover will open at a predetermined time [23]. Manyazewal and the team also used a MERM system with a tool called evriMED500, in the form of a pillbox consisting of a medicine container and an electronic module connected to an indicator light and an alarm [35,36]. The MERM system in the study did not show superiority over the standard care of the control group. However, it should be recognized that the adherence dimension has many independent variables that may play a large role in influencing interventions. Unfortunately, the study of the use of the MERM system that we found did not carry out an analysis of the potential factors. So that bias in the study is likely to occur.

Another device used is Wirelessly Observed Therapy (WOT), a sensory device that enters the body through the mouth. A patch detector in the torso area will read all sensor activity. The data recorded from the patch detector is transmitted wirelessly via Bluetooth technology to mobile phones, computers, or other gadgets [50]. Browne stated that WOT is very safe to apply without significant side effects, only in the form of minimal irritation due to the direct use of patches on the skin [28]. Statistically, WOT is superior to DOT; in other words, WOT is effective in increasing TB patient adherence to treatment. However, the application of WOT is likely to be constrained, especially in countries with lower middle incomes, because this technology is still relatively expensive, and there are suggestions to replace the patch every five days to avoid irritation [28]. Previous studies have also confirmed that using WOT can increase adherence to antiviral HCV therapy in populations at high risk of non-adherence [51].

Another hardware option we found in one study was the use of e-DOT in real-time or recorded video, depending on patient preference [29]. Real-time video allows patients to interact directly with TB program officers with the help of Skype software. Burzynski and colleagues found that e-DOT is similar to in-person-DOT but has equal effectiveness. For this reason, e-DOT can be applied according to the patient’s choice. Especially during a pandemic such as COVID-19, electronic DOT is the best choice to reduce the spread and worsen TB patients’ conditions, as found by Lippincott and colleagues in implementing the Vdot COVID-19 pandemic where this method has high effectiveness and is the first choice. In contrast, in-person DOT is recommended to be carried out later [52]. Haberer and Subbaraman added that implementing eDOT might encounter technical challenges, inaccuracies, costs, and an unsupportive health system [47].

The potential of mHealth on TB patient adherence

Compliance of TB patients with the treatment program can be seen from the success of the treatment. Of the various types of mHealth that we collected, almost all showed an increase in adherence of TB sufferers to the treatment given. Although, comparison with the control group mostly showed insignificant differences.

The use of SMS text generally shows more potential than the DOT standard. Two studies show that compliance with TB patients using SMS text interventions is similar to DOT standards [32,33]. The study states that there may be several factors that influence the failure of TB patient compliance even though they have been reminded via SMS messages, including the lack of more personalized engagement, the didactic nature of the messages, and the SMS message is received when the patient was not near his/her medication all contributed to the failure to reduce poor adherence [53]. For this reason, in the future, this can be a consideration in implementing interventions using text SMS, where controlling these situations is essential to consider. However, based on the success of increasing adherence from studies using text SMS, it was stated that patient compliance was one time greater than the DOT standard. The same thing was also found in the use of Whatsapp, where significant treatment success occurred in TB patients who were given education through messages via Whatsapp [40].

The medication event reminder monitor (MERM) system in studies using it also shows positive potential to improve TB patient adherence to treatment. In addition, using MERM can also reduce the workload of health workers [54]. One problem identified using MERM is the possibility of removal of the medication from the pillbox, for example, for work-related reasons, which prevents the recording of pill dispensing. Although the potential of MERM is not superior to in-person DOT, MERM can be used as an alternative to improve TB patient compliance. The identical thing is also found in using electronic DOT and WOT. This hardware allows stricter supervision and accurate recording of each drug-taking activity so that health workers can more easily measure treatment success.

LIMITATION

The limitations encountered in this review include limited access to several reputable databases, which does not allow us to explore further relevant articles. In addition, this review includes studies of low to high quality due to the small number of articles we have collected. For this reason, writers who want to use the results of this review must be careful and analyze them more carefully.

CONCLUSION

This review shows that using m-Health can be the first choice in handling TB cases with the DOT strategy. Hardware as part of mHealth has more potential to increase TB patient adherence and behaviour change. TB patient compliance with medication programs and stopping the spread of TB through good behaviour will be very significant in reducing TB cases, recurrent cases and new cases. mHealth is the best choice as a companion to the ongoing DOT program, primarily as a medium for disseminating information needed by patients during their treatment period. In the era of digitalization today and in the future, mHealth is undoubtedly the main route in health services, as illustrated during the pandemic of certain diseases that did not allow face-to-face meetings. However, further efficacy studies at the clinical level are needed, while always protecting privacy.

REFERENCES

- Acharya B, Acharya A, Gautam S, Ghimire SP, Mishra G, Parajuli N, et al. Advances in diagnosis of Tuberculosis: an update into molecular diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular biology reports. 2020;47:4065–75.

- Asriati A, Kusnan, Adius, Alifariki L. Faktor Risiko Efek Samping Obat dan Merasa Sehat Terhadap Ketidakpatuhan Pengobatan Penderita Tuberkulosis Paru. JURNAL KESEHATAN PERINTIS (Perintis’s Health Journal). 2019;6(2):134–9.

- Putri S, Alifariki LO, Fitriani F, Mubarak M. The Role of Medication Observer And Compliance In Medication Of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patient. Jurnal Kesehatan Prima [Internet]. 2020 Feb 29;14(1). Available from: http://jkp.poltekkes-mataram.ac.id/index.php/home/article/view/248

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tuberculosis [Internet]. 27 October 2022. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- Harding E. WHO global progress report on tuberculosis elimination. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020;8(1):19.

- Dean AS, Auguet OT, Glaziou P, Zignol M, Ismail N, Kasaeva T, et al. 25 years of surveillance of drug-resistant tuberculosis: achievements, challenges, and way forward. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022;

- Ghozali MT, Murani CT. Relationship between knowledge and medication adherence among patients with tuberculosis: a cross-sectional survey. Bali Medical Journal. 2023;12(1):158–63.

- Asriati A. Faktor Risiko Ketidakpatuhan Pengobatan Penderita Tuberkulosis Paru di Kota Kendari. Jurnal Keperawatan Terapan (e-Journal). 2019;5(2):103–10.

- World Health Organization. Digital health for the End TB Strategy: an agenda for action. World Health Organization; 2015.

- El Emeiry F, Shalaby S, El-Magd GHA, Madi M. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis among new smear-positive and retreatment cases: a retrospective study in two Egyptian governorates. The Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis. 2019;68(3):274.

- Ying R, Huang X, Gao Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Sha W, et al. In vitro Synergism of Six Antituberculosis Agents Against Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolated from Retreatment Tuberculosis Patients. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2021;3729–36.

- Margineanu I, Louka C, Vincenti-Gonzalez M, Saktiawati AMI, Schierle J, Abass KM, et al. Patients and medical staff attitudes toward the future inclusion of ehealth in tuberculosis management: perspectives from six countries evaluated using a qualitative framework. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(11):e18156.

- Zhang J, Yang Y, Qiao X, Wang L, Bai J, Yangchen T, et al. Factors influencing medication nonadherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment in tibet, china: a qualitative study from the patient perspective. Patient preference and adherence. 2020;1149–58.

- World Health Organization. Handbook for the use of digital technologies to support tuberculosis medication adherence. World Health Organization; 2017.

- Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(2):e52.

- Bartels SL, Van Knippenberg RJM, Dassen FCM, Asaba E, Patomella A-H, Malinowsky C, et al. A narrative synthesis systematic review of digital self-monitoring interventions for middle-aged and older adults. Internet interventions. 2019;18:100283.

- He Q, Zhao X, Wang Y, Xie Q, Cheng L. Effectiveness of smartphone application–based self‐management interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of advanced nursing. 2022;78(2):348–62.

- Zhu MM, Choy BNK, Lam WWT, Shum J. Randomized control trial of the impact of Patient Decision Aid (PDA) developed for Chinese primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Ophthalmic Research. 2023;

- Hirsch-Moverman Y, Daftary A, Yuengling KA, Saito S, Ntoane M, Frederix K, et al. Using mHealth for HIV/TB treatment support in Lesotho: enhancing patient–provider communication in the START study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2017;74(Suppl 1):S37.

- Mohammed S, Glennerster R, Khan AJ. Impact of a daily SMS medication reminder system on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one. 2016;11(11):e0162944.

- Farooqi RJ, Ahmed H, Ashraf S, Zaman M, Farooq S, Farooqi JI. Feasibility and acceptability of Mobile SMS reminders as a Strategy to improve drugs adherence in TB Patietns. Pakistan Journal of Chest Medicine. 2017;23(3):93–100.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery. 2021;88:105906.

- Acosta J, Flores P, Alarcon M, Grande-Ortiz M, Moreno-Exebio L, Puyen ZM. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate a medication monitoring system for TB treatment. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2022;26(1):44–9.

- Ali AOA, Prins MH. Mobile health to improve adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Khartoum state, Sudan. Journal of Public Health in Africa. 2019;10(2).

- Bao Y, Wang C, Xu H, Lai Y, Yan Y, Ma Y, et al. Effects of an mHealth intervention for pulmonary tuberculosis self-management based on the integrated theory of health behavior change: randomized controlled trial. JMIR public health and surveillance. 2022;8(7):e34277.

- Bediang G, Stoll B, Elia N, Abena J-L, Geissbuhler A. SMS reminders to improve adherence and cure of tuberculosis patients in Cameroon (TB-SMS Cameroon): a randomised controlled trial. BMC public health. 2018;18:1–14.

- Boutilier JJ, Yoeli E, Rathauser J, Owiti P, Subbaraman R, Jónasson JO. Can digital adherence technologies reduce inequity in tuberculosis treatment success? Evidence from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(12):e010512.

- Browne SH, Umlauf A, Tucker AJ, Low J, Moser K, Gonzalez Garcia J, et al. Wirelessly observed therapy compared to directly observed therapy to confirm and support tuberculosis treatment adherence: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS medicine. 2019;16(10):e1002891.

- Burzynski J, Mangan JM, Lam CK, Macaraig M, Salerno MM, deCastro BR, et al. In-person vs electronic directly observed therapy for tuberculosis treatment adherence: A randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(1):e2144210–e2144210.

- Gashu KD, Gelaye KA, Lester R, Tilahun B. Effect of a phone reminder system on patient-centered tuberculosis treatment adherence among adults in Northwest Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Health & Care Informatics. 2021;28(1).

- Gupta A, Bhardwaj AK, Singh H, Kumar S, Gupta R. Effect of ‘mHealth’Interventions on adherence to treatment and outcomes in Tuberculosis patients of district Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India: A Randomised Control Trial. Indian Journal of Preventive & Social Medicine. 2020;51(3):125–36.

- Johnston JC, van der Kop ML, Smillie K, Ogilvie G, Marra F, Sadatsafavi M, et al. The effect of text messaging on latent tuberculosis treatment adherence: a randomised controlled trial. European Respiratory Journal. 2018;51(2).

- Kibu OD, Siysi VV, Albert Legrand SE, Asangbeng Tanue E, Nsagha DS. Treatment Adherence among HIV and TB Patients Using Single and Double Way Mobile Phone Text Messages: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2022;2022.

- Louwagie G, Kanaan M, Morojele NK, Van Zyl A, Moriarty AS, Li J, et al. Effect of a brief motivational interview and text message intervention targeting tobacco smoking, alcohol use and medication adherence to improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes in adult patients with tuberculosis: a multicentre, randomised controlled tri. BMJ open. 2022;12(2):e056496.

- Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Holland DP, Fekadu A, Marconi VC. Effectiveness of a digital medication event reminder and monitor device for patients with tuberculosis (SELFTB): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC medicine. 2022;20(1):310.

- Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Getinet T, Hoover A, Bobosha K, Fuad O, et al. Patient-reported usability and satisfaction with electronic medication event reminder and monitor device for tuberculosis: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;56:101820.

- Ratchakit-Nedsuwan R, Nedsuwan S, Sawadna V, Chaiyasirinroje B, Bupachat S, Ngamwithayapong-Yanai J, et al. Ensuring tuberculosis treatment adherence with a mobile-based CARE-call system in Thailand: a pilot study. Infectious Diseases. 2020;52(2):121–9.

- Santra S, Garg S, Basu S, Sharma N, Singh MM, Khanna A. The effect of a mhealth intervention on anti-tuberculosis medication adherence in Delhi, India: A quasi-experimental study. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2021;65(1):34.

- Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E, Burger R. SMS nudges as a tool to reduce tuberculosis treatment delay and pretreatment loss to follow-up. A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218527.

- Haslinda N, Juni MH. Effectiveness of health education module delivered through Whatsapp to enhance treatment adherence and successful outcome of tuberculosis in Seremban district, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences. 2019;6(4):145–59.

- Boutilier JJ, Jónasson JO, Yoeli E. Improving tuberculosis treatment adherence support: the case for targeted behavioral interventions. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 2022;24(6):2925–43.

- Das Gupta D, Patel A, Saxena D, Koizumi N, Trivedi P, Patel K, et al. Choice‐Based Reminder Cues: Findings From an mHealth Study to Improve Tuberculosis (TB) Treatment Adherence Among the Urban Poor in India. World Medical & Health Policy. 2020;12(2):163–81.

- Laksono EB, Johan A, Erawati M. The Utilization of Mobile-Health Intervention In Improving Treatment Compliance Behavior In Tuberculosis Patients. Nurse and Health: Jurnal Keperawatan. 2022;11(2):275–86.

- Shariful IM. Theories applied to m-health interventions for behavior change in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2018;

- Nglazi MD, Bekker L-G, Wood R, Hussey GD, Wiysonge CS. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13(1):1–16.

- Sarabi RE, Sadoughi F, Orak RJ, Bahaadinbeigy K. The effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging in improving medication adherence for patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2016;18(5).

- Haberer JE, Subbaraman R. Digital technology for tuberculosis medication adherence: promise and peril. Vol. 17, Annals of the American Thoracic Society. American Thoracic Society; 2020. p. 421–3.

- Lucya V. Prevention of Tuberculosis: Literature Review. KnE Life Sciences. 2021;630–4.

- Lönnroth K, Roglic G, Harries AD. Improving tuberculosis prevention and care through addressing the global diabetes epidemic: from evidence to policy and practice. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2014;2(9):730–9.

- Hafezi H, Robertson TL, Moon GD, Au-Yeung K-Y, Zdeblick MJ, Savage GM. An ingestible sensor for measuring medication adherence. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2014;62(1):99–109.

- Bonacini M, Kim Y, Pitney C, McKoin L, Tran M, Landis C. Wirelessly observed therapy to optimize adherence and target interventions for oral hepatitis C treatment: observational pilot study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(4):e15532.

- Lippincott CK, Perry A, Munk E, Maltas G, Shah M. Tuberculosis treatment adherence in the era of COVID-19. BMC infectious diseases. 2022;22(1):800.

- Liu X, Lewis JJ, Zhang H, Lu W, Zhang S, Zheng G, et al. Effectiveness of electronic reminders to improve medication adherence in tuberculosis patients: a cluster-randomised trial. PLoS medicine. 2015;12(9):e1001876.

- Wang N, Zhang H, Zhou Y, Jiang H, Dai B, Sun M, et al. Using electronic medication monitoring to guide differential management of tuberculosis patients at the community level in China. BMC infectious diseases. 2019;19(1):1–9.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EFFECT OF GUIDED EDUCATION ON PERCEPTION AND ATTITUDE OF CHILDBEARING WOMEN TOWARDS CAESAREAN SECTION IN NIGERIA

Mary Idowu Edward1*, Oluwaseun Segun Bolarinwa2,

Omowumi Suuru Ajibade3, Temilola Mabel Aregbesola4

1,2,3, Department of Adult and Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Science, University of Medical Sciences, Akure Campus, Akure, Ondo State,

4Basic Health Center Iloro, Akure, South, Ondo State, Nigeria

Corresponding Author: Mary Idowu Edward RN, RM, RNE, PhD. Nursing. Department of Adult and Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Science, University of Medical Sciences, Akure Campus, Akure, Ondo State. Email: edwardmary@unimed.edu.ng

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Background: Nigerian women are unwilling to have a Caesarean section because of the general belief that abdominal delivery is a reproductive failure on their part regardless of the feasibility of vaginal birth after Caesarean section and the decreasing mortality from Caesarean sections.

Aim: The primary objective of this study was to investigate the existence of a significant relationship between pregnant women’s knowledge and attitudes toward cesarean delivery before and after training.

Materials and Methods: The study employed a pre/post-test study design, using questionnaires to obtain data from 152 childbearing women attending antenatal in Iloro Basic Health Centre, Akure, Ondo State. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and present data. Associations between variables were tested using Spearman correlation at a p-value 0.05 level of significance.

Results: The researcher found a significant relationship between the knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards Caesarean section delivery before and after the training. The findings revealed an increase in the knowledge of mothers after the educational intervention, mothers would opt for a Caesarean section if it is necessary to protect them and the baby and they believe that it is a woman’s right to choose a Caesarean section for herself. Significant relationship exists between knowledge and attitudes toward the Caesarean section.

Conclusion: It was concluded that childbearing mothers still believe that vagina delivery is a natural delivery and there is joy attached to it, however, most women would still prefer vagina delivery to Caesarean section. The study recommends a need for awareness programs to enhance women’s and the community positive perception towards the Caesarean section in Nigeria.

Keywords: Guided Education, Perception, Attitude, Childbearing women, Caesarean Section

Introduction

Worldwide, Caesarean section accounts for about 15% of births. Caesarean section is one of the oldest procedures in obstetric practice and may be a necessary end in the termination of pregnancy to abort or minimize complications to the mother, foetus, or both [1]. At the onset, the operation was associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, largely because of the low level of medical science available at the time [2]. This type of surgery has been in existence throughout medical history and has steadily progressed from being one that is totally fatal to one that is safe for both the mother and the foetus [1]. In developed countries, the operation of Caesarean section has become well established with ease and safety, hence there is a lure for the procedure with women opting for it, increasingly for non-medical reasons [3]. It is the most commonly performed major obstetric operation in the world and there is no doubt that it has contributed to improved obstetric care throughout the world [4]. In Africa, the cesarean section is usually performed when a vaginal birth is deemed hazardous either to the foetus or the mother [5].

Available evidence pertaining to the population-based prevalence of Caesarean section in Nigeria reveals a threshold that is, far below the 10% recommended by the WHO [5]. Moreover, there has been no significant increase in the population-based Caesarean section rates for several years in Nigeria [7]. For instance, in 2008, merely 2% of births were delivered through a Caesarean section in Nigeria, and the rate remained unchanged in 2013. This is considerably low and suggests unmet needs which may contribute to poor maternal and neonatal outcomes in the country [5].

Interestingly, pregnant women’s perception of Caesarean section has been an essential consideration for providers of healthcare in the USA [7]. One of the major reasons is that a positive perception can lead to an effective adaptation to the maternal role whiles a negative perception can leave women with a sense of failure, loss of control, personal disappointment, and a cause to distrust their personal abilities as childbearing women, hence the need to promote positive perceptions in Caesarean section related issues [8]. For a healthy women population, the choice of delivery option is an important decision [9]. In developing countries, the negative perception of Caesarean section has led to the under utilization of the procedure[9]. Although there are many who consider the Caesarean section to be either safe or unsafe, more costly than the normal vaginal delivery, and more prone to complications than the SVD, there are some African women who perceive a Caesarean section to be a sign of female infidelity, a “curse,” or a “failure of womanhood”.

In a study carried out to assess the attitude of women toward a Caesarean section in Nigeria, it was found that vaginal delivery was the preferred mode of delivery by 93% of the respondents while 7% preferred a Caesarean section as the mode of delivery [11]. Expectant parents make many choices which usually include the site for delivery and the choice between spontaneous vaginal delivery and Caesarean section [10]. The reasons for this choice are being a natural process, being good for the mother’s health, and safety, and being an easy process [12]. Most of the women thought that Caesarean delivery can lead to long-term ill effects on the mother’s health. All the women who preferred elective Caesarean delivery initially said that they would rather opt for painless labour and vaginal delivery if offered over Caesarean section [11].

Nonetheless, the world health body emphasizes the need for Caesarean section service provision to every woman in need of it regardless of the prevailing population-based rates [13]. When medically indicated, Caesarean section has the potential for reducing maternal/neonatal mortalities and morbidities including delivery complications such as obstetric fistula [14]. However, a non-medically indicated Caesarean section has no associated additional benefits for mothers and newborns, rather like any surgery, it carries both short-term and/or long-term health risks [14]. Some studies have been conducted on Caesarean section utilization in Nigeria including a survey that examined the perception of pregnant women and found that a high proportion of the study participants were averse to Caesarean section delivery [5]. Significant associations between Caesarean section and parity, maternal weight, child’s birth weight, and previous Caesarean section were reported in another study [13]. However, it is not strange to hear many pregnant women ventilating the wrong attitude toward Caesarean section as an alternative method of birth [15]. In Nigeria, a number of women believe a Caesarean section is a last resort used to deliver pregnant women of their babies, many will even say, being told that they are going to deliver their babies through a Caesarean section is like giving a death warrant [13].

Traditionally, Nigerian women are unwilling to have a Caesarean section because of the general belief that abdominal delivery is a reproductive failure on their part regardless of the feasibility of vaginal birth after Caesarean section and the decreasing mortality from Caesarean sections. Inaccurate cultural perception about Caesarean section delivery accounts for the poor attitude of women towards Caesarean section [5]. Only one-third of women demonstrate a positive attitude towards Caesarean delivery as against 95.5% for vaginal delivery in the same group of respondents. The study concluded no significant differences in attitude and knowledge scores according to women’s levels of education [16]. It is necessary to note that the issue of vaginal birth is not only peculiar to developing countries but also to some developed countries. Women still choose vaginal birth after having a Caesarean section even in the case of postdates slated for elective Caesarean section. Hence, it is imperative to educate the average pregnant woman irrespective of her level of education and parity on Caesarean section. Therefore, this study assessed the effect of guided education on the perception and attitude of childbearing women toward Caesarean section.

Objectives of the study

- The primary objective of this study was to investigate the existence of a significant relationship between pregnant women’s knowledge and attitudes toward cesarean delivery before and after training.

- The secondary objective of the study was to describe the levels of knowledge and attitude of childbearing mothers about cesarean section before and after the educational intervention and the factors for not accepting cesarean section as a mode of delivery among women.

Hypothesis

HO1: There is no significant relationship between the knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards Caesarean section delivery before and after the intervention.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Population, and Area

The study utilized a quasi-experimental pre/post-test design. This design was adopted by the researcher because it will help to ascertain the effect of guided education on the perception and attitude of childbearing women towards Caesarean section in Basic Health Center Iloro, Akure South Local Government Area. The research setting for this study is Basic Health Center Iloro, Akure South Local Government Area. The head-quarter of Akure South Local government area is Akure town. Akure is a city in southwestern Nigeria and the capital of Ondo State. The metro area population of Akure in 2022 was 717,000 a 3.76% increase from 2021 which was 691,000[17]. Basic Health Center Iloro is a step above your ordinary health center, they make the provision of primary health care a full package. Health professionals and caregivers are available to give postnatal care.

The population of this study was composed of childbearing women attending the antenatal clinic in Basic Health Center Iloro, Akure South Local Government Area. The study population was randomly selected.

Sample Size Estimation, Sampling Technique, Data, collection, and Analysis

To estimate the minimum number n of childbearing women to investigate the effect of guided education on the perception and attitude toward Caesarean section, we considered the Gaussian theory [18]:

where N is the population size from which the sample size was defined. It resulted that the minimum estimated sample size of childbearing women required for a survey of a population of 255 mothers is equal to 143. It is evaluated, considering a z-score at 95%, an error e = 10% and hypothesizing a prevalence p equal to 70% about the impact of guided education. In addition to reduce statistical biases connected to information/data loss the sample size is enlarged to 152 mothers.

Instruments

The research instrument used was developed ad hoc, considering an extensive search of empirical studies on caesarian sections and was administered before and after the nurse-led education [9,19,21,22,23]. The instrument has the following sections: Demographic characteristics of the respondents (7 items), knowledge of childbearing mothers on caesarean section (8 items), perception of the childbearing mother towards the caesarean section (7 items) and the attitude of a childbearing mother towards the caesarean section (10 items), and factors for not accepting caesarean section as the mode of delivery among the women (8 items). The reliability test of the instruments was Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.83. The demographic, knowledge and factor data were scored using frequency and percentage while perception and attitude data were scored using 3 point likert scale of Agree, Not Sure and Disagree while factors data was obtained using 5 likert scale of strongly agree, agree, Not Sure, disagree and stongly disagree.

Procedure for data collection

The data was collected over a period of 4 weeks. All pregnant women were qualified to be included in the study hence need to randomly select about 20 manageable women during the antenatal visit (two Antenatal clinics per week) out of more than 60 attendance to prevent disruption of antenatal clinic activities and efficiency in data collection. The selected 20 women having been informed about the study and consent gained were administered the pretest. The education intervention which is already prepared materials on what Caesarean section is, when is it needed, types, and how to prepare for a Caesarean section are included in the module of training. The questionnaires were administered at the end of the intervention, that is, post-test.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis like percentages and frequency tables were used to present the summary of the data, Cronbach’s alpha was utilised to test reliability of the instrument and Spearman correlation was used to test the hypotheses – relationship between knowledge and attitude at a 0.05 level of significance. Data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 20. The knowledge variable was defined by assigning points based on the affirmative response of Yes or No. For example if the number of participants who has correct answer to the questions is below 50%, 1point is assigned, if they are between 50-75% 2 points is assigned while 3points is assigned for participants between 76-100%. The maximum obtainable points of 8 knowledge items is 24 points while the minimum is 8 points. Therefore knowledge is graded thus: 1-8(Low knowledge).9-16 (Medium knowledge) while 17-24 (High Knowledge). The Perception and attitude were scored based on 3 points likert scales thus: Agree(3), Disagree (2) and Not Sure (1). the maximum obtainable score for Perception (7 items) is 21 and the minimum is 7. The maximum obtainable scores for attitude is 30 while the minimum is 10. Factors questionaires were graded on 5 points likert scales. The maximum obtainable mark is 35 while the minimum is 7.

Ethical considerations

Letter of introduction and intention of the study was taking to the Primary Health Care Authority and written permission was obtained. The study is not an invasive study, no formal approval by the Local Ethics Committee was required for this study hence no protocol number was indicated on the letter but the reference number PHCA/AK-S/020/124. However, the participants informed consent were obtained and willingness to participate was expressed before inclusion in the study. All participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality.

Results

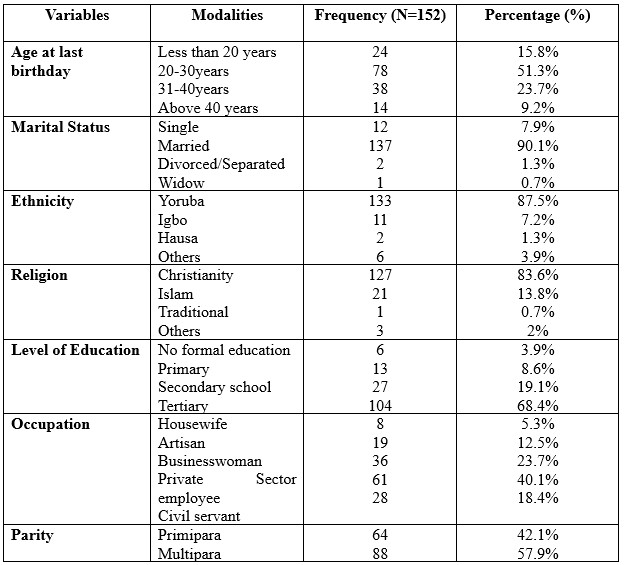

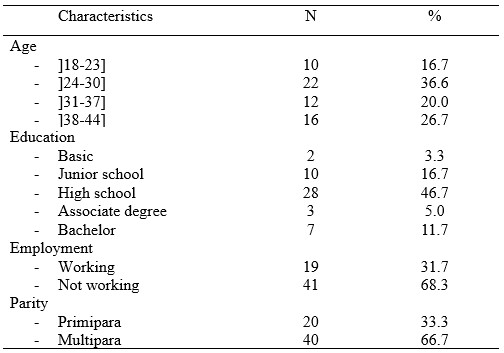

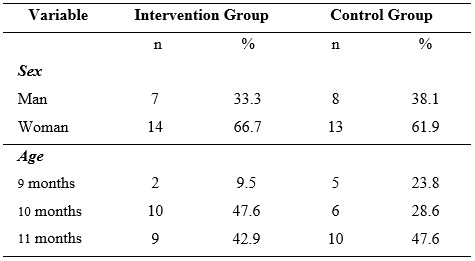

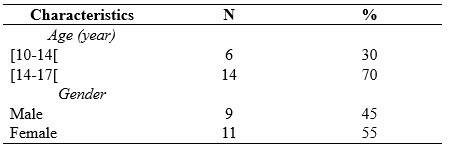

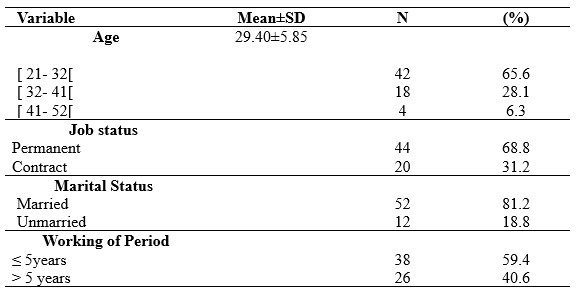

Table 1 revealed the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the 152 respondents.

The respondents are 152 in number. Of the 152 respondents, 51.3% of the participants fall in the

age group between 20-30 years, and 90.1% are married. 87.5% are Yoruba and 83.6% are Christians. Findings further showed that 68.4% had tertiary education, 40.1% were private sector employees and 57.9% were multipara.

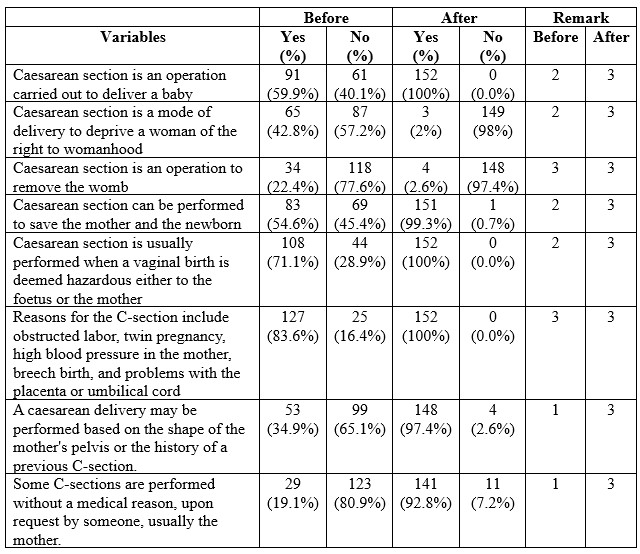

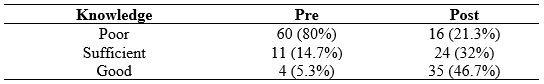

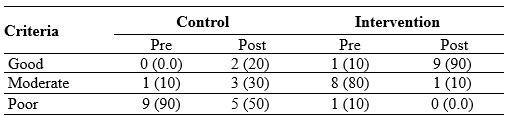

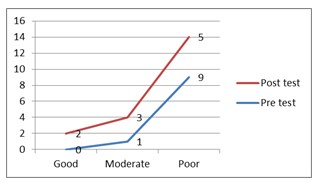

Table 2 above shows the knowledge of childbearing mothers on Caesarean section. Before the intervention, the participants had medium knowledge, that is, the score of 16 which is 66.7% of the responses from study participants while after the intervention, the participants had high knowledge of Caesarean section, that is, the score of 24 which is (100%) of obtainable knowledge scores.

Table 2. Knowledge of 152 childbearing mothers on Caesarean section

Table 3 below shows the perception of childbearing mothers toward Caesarean section. The training improves the perception of mothers toward Caesarean as a method mode of delivery. All the respondents (100%) stated that vaginal delivery is a natural and acceptable mode of delivery.

Table 3. Perception of 152 childbearing mothers toward Caesarean section.

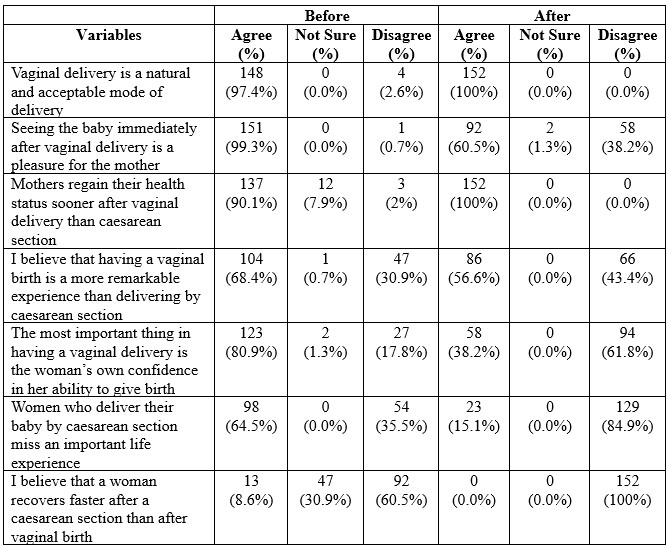

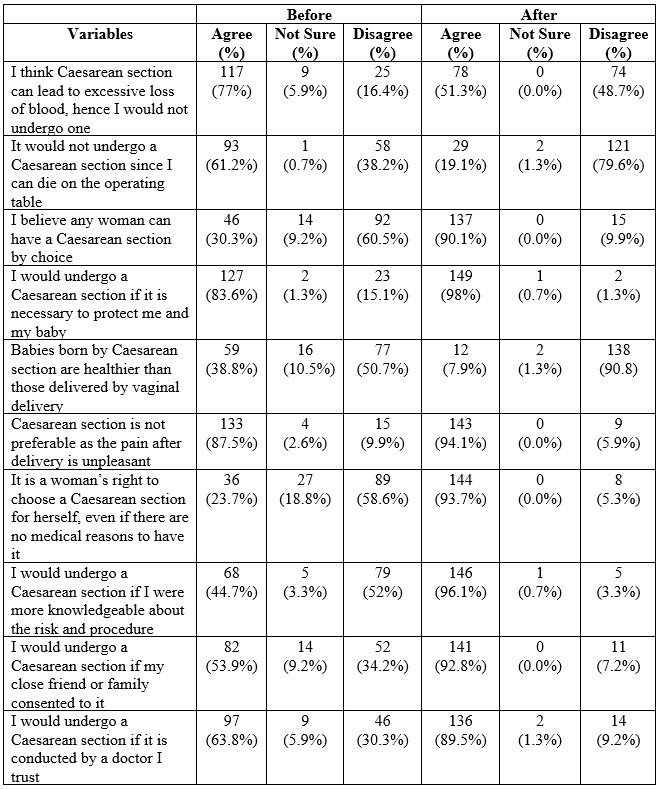

Table 4 below shows the attitude of childbearing mothers towards Caesarean section as the accepted mode of delivery among women. Before the training, many mothers had negative attitudes towards Caesarean but this improves after the training.

Table 4. The attitude of 152 childbearing mothers towards Caesarean section.

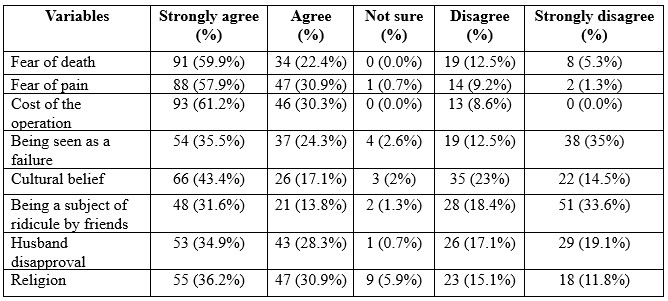

Table 5 above shows factors for not accepting Caesarean section as the mode of delivery among women. The women stated that fear of death, fear of pain, cost of the operation, cultural belief, being a subject of ridicule by friends, husband disapproval, and religion for not accepting Caesarean section as the mode of delivery among the women.

Table 5. Factors for not accepting Caesarean section as the mode of delivery among 152 women.

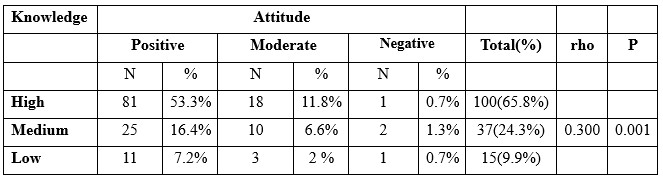

Table 6. Spearman correlation between knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards caesarean section delivery.

Spearman correlation analysis test was carried out to determine the relationship between knowledge and attitudes, obtained p < 0.001 indicating that p <0.05. H0 is rejected and H1 is accepted, it can be concluded that there is a significant relationship between knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards caesarean section delivery. It is found that rho = 0.300 and the direction of positive correlation (+). It can be concluded that the strength of the correlation between knowledge and attitude is low, which means that even though in this study there is a significant relationship between the two variables, there are still many factors that influence knowledge and attitude. The results of this study also show a positive correlation direction (+), which means that the relationship between knowledge and unidirectional attitude – meaning that the higher one’s knowledge, the better the attitude.

Discussion of findings

The discussions made on the findings of this study are presented in accordance with the research questions. The sub-headings under which the discussions are provided show in specific what each research question seeks to find.

Demographic characteristics of respondents

Findings from this study revealed that the average age of the respondents is 27 years. The majority (90.1%) were married and multipara and the population were dominated by Yoruba and Christians. More than half of the respondents had tertiary education. This was similar to the study of [19] on the attitude of pregnant women in southwestern Nigeria. The findings are in line with the study of [19]on the perception and attitude of pregnant women towards Caesarean section delivery in the University of Port-Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, in which the majority of respondents between the age group of 25-29 years, and 85.9% were married.

Knowledge of childbearing mother on Caesarean section

Based on the findings from this study, it was revealed that there was an increase in the knowledge of mothers after the educational intervention on Caesarean section. The increased level of knowledge among pregnant women may be attributed to the educational intervention and information provided during the training. This is in consonant with the study of [20,21,22] who reported that majority of the women have good knowledge about caesarean section. The study of [23] on pregnant women’s knowledge, perception, and attitudes towards the Caesarean section also showed that the majority of women had adequate knowledge and were aware of all of the factors concerning Caesarean section deliveries. This study was in contrast with the study of [24] who reported good knowledge of 17.4% on Caesarean section delivery. [25] also found that there was a low overall knowledge of mothers about the modes of delivery.

Perception of the Childbearing Mothers towards Caesarean section

The findings from this study revealed that the majority of mothers had a poor perception of a Caesarean section before the training; however, there was an increase in the mothers’ score on the perception of Caesarean section among childbearing mothers after the intervention. Childbearing mothers still believe that vagina delivery is a natural delivery and has joy attached to it, and most women still prefer it over Caesarean section[25]. The study of [27] reported that having a Caesarean section takes away from the joy of giving birth and was of the view that Caesarean section births are not natural and should be reserved for those with medical issues or those who fear pain.

The attitude of Childbearing Mothers toward Caesarean section

The findings from this study revealed improved scores in the attitude of mothers toward Caesarean section. The majority of the mothers reported that they would opt for Caesarean section if it is necessary to protect them and their babies, and they believe it is a woman’s right to choose a Caesarean section for herself, even if there are no medical reasons to have it. They were also of the opinion that Caesarean section is not preferable as the pain associated with it post-delivery is unpleasant. Although before the training majority thought Caesarean section can lead to excessive loss of blood and they could die on the operating table. This assertion corresponds to the finding of [23] who submitted that the fear of death, complications, and other negative perceptions about Caesarean section make women unwilling to opt for it. The study of [28] on perception and attitude towards Caesarean section in Niger/Delta reflected that 83.2% of mothers would accept Caesarean section if it is a necessity that will protect them and their babies [29].

Factors for not accepting Caesarean section as the mode of delivery among the women

Findings from this study revealed fear of death, fear of pain, cost of the operation, being seen as a failure, cultural belief, husband disapproval, and religion were the factors revealed by the mothers for not accepting Caesarean section as the mode of delivery. [31] listed fear of death, denial of womanhood, expensive mode of delivery, and the possibility of being exposed to insults as reasons for opposing Caesarean section for delivery. [29] stated maternal autonomy, women empowerment and gender inequality as several women often need to take permission from their husbands and/or religious leaders before making health-related decisions[29]. According to [30] women’s decision-making in consultation with relatives is the main influencer to accept elective caesarean section.

Discussion of the hypothesis

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the existence of a significant relationship between pregnant women’s knowledge and attitudes toward cesarean delivery before and after training. The secondary objective of the study was to describe the levels of knowledge and attitude of childbearing mothers about cesarean section before and after the educational intervention and the factors for not accepting cesarean section as a mode of delivery among women. Based the inferential statistics carried out in this study, it was revealed that there is a significant difference between the pre and post-intervention knowledge of Caesarean section, and pre and post-intervention attitudes of pregnant women towards Caesarean section delivery. Similarly, [32] found a significant difference between pre and post-intervention knowledge and pre and post-intervention attitudes of pregnant women to Caesarean section. Contrary to these findings, there was no significant association between knowledge about Caesarean section and respondents’ characteristics in relation to age, marital status, occupation, and previous place of delivery [33].

Conclusions

Nigerian women are unwilling to have Caesarean section because of the general belief that abdominal delivery is a reproductive failure on their part regardless of the feasibility of vaginal birth after a Caesarean section and the decreasing mortality from Caesarean sections. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the existence of a significant relationship between pregnant women’s knowledge and attitudes toward cesarean delivery before and after training. The secondary objective of the study was to describe the levels of knowledge and attitude of childbearing mothers about cesarean section before and after the educational intervention and the factors for not accepting cesarean section as a mode of delivery among women. The study revealed an increase in the mothers’ knowledge about Caesarean section after the intervention. In addition, both perception and attitude towards Caesarean section improved following the intervention. The researchers found a significant relationship between the knowledge and attitude of pregnant women towards Caesarean section delivery before and after the intervention. It was concluded that the childbearing mothers still believe that vagina delivery is a natural delivery and there is joy attached to it, most women would only agree to have Caesarean section if the need arises but they would still prefer spontaneous vagina delivery.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made:

- There is still a need for awareness programs to increase women’s and community’s understanding about Caesarean section in Nigeria.

- Our society needs further enlightenment on the advantages of antenatal care attendance and hospital deliveries as the problem is rooted in our culture.

- Local, State and Federal Governments should subside the costs of maternity services through an all-inclusive National Health Insurance Scheme. This will go a long way to encourage women to accept Caesarean section when the need arises.

Limitations

The research was carried out in just one health center (Iloro Comprehensive Health Center) in Akure Local government are of Ondo State due limited funds. Future research should utilise more facilities to enhance generalisation.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding:

None declared. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Author contributions: All authors equally contributed to the conduct of this study and to preparing this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Management of Basic Health Centre Iloro, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria, and all the mothers that participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

- Cunningham, F.G., MacDonald, P.C., Gant, N.F., Leveno, K.J, Gilstrap, L.C. & Hankins, G. (2017). Caesarean delivery and Caesarean In: Cunningham, et al, editors. Williams Obstetrics, 20th edition. Stamford, CF: Appleton & Lange; p. 509-31.

- Kerr-Wilson R. (2018). Caesarean section on demand. In: Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Harcourt Publishers: 126-28.

- Gomen, R., Tamir, A. & Degani, S. (2014). Obstetricians’ opinions regarding patient choice in caesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol.;99(4):577 -80.

- Ohanson, R.B., EI-Timini, S., Rigby, C., Young, P. & Jones P. (2019). Caesarean section by choice could fulfi11the inverse care law. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod BioI.;97(1):20-2.

- Ezeonu,P. O.. Ekwedigwe, K. C., Isikhuemen,M. E., Eliboh,M. O., Onoh, R. C., Lawani,L. O., Ajah,L. O. & Dimejesi,E. I. (2017). Perception of Caesarean Section among Pregnant Women in a Rural Missionary Hospital.Advances in Reproductive Sciences, Vol.5 No.3.

- Egwuatu, V.B. & Ezeh, I.O. (2018). Vaginal delivery in Nigeria Women after a previous section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet.;32: 1-6

- Coleman, V.H., Lawrence, H. & Schulkin, J. (2019). Rising Cesarean Delivery Rates. The Impact of Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request. CME review article 4. ObstetGynecol survey.; 64: 2.

- Penna, L. (2014). Caesarean section on request for non-medical indications. Current Obstet. Gynaecol.; 14: 220-223.

- Naa Gandau, B.B., Nuertey, B.D., Seneadza, N.A.H. et al. Maternal perceptions about caesarean section deliveries and their role in reducing perinatal and neonatal mortality in the Upper West Region of Ghana; a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 350 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2536-8

- Danon, D., Sekar, R., Hack, K.E & Fisk, N.M. (2013). “Increased stillbirth in uncomplicated monochorionic twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (6): 1318–26. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318292766b. PMID 23812469. S2CID 5152813.

- Onah H.E. & Ugona M.C. (2014). Preference for Caesarean section or symphysiotomy for obstructed labour among Nigerian women. IJOG 2004; 84: 70-91.

- Ezechi, O.C., Fasuba, O.B., Kalu, B.E., Nwokolo, C.A. & Obiesie, L.O. (2014). Caesarean Delivery: Why the aversion? Trop J ObstetGynaecol.; 21 (2): 164-167.

- Chigbu, C. & Iloabachie, G. (2017). The burden of Caesarean section refusal in a developing country setting. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology; 114: 1261 – 1265.

- Bonney, E.A. & Myers, J.E. (2015). Caesarean section: Techniques and complications. Obstet. Gynaecol Rep Med; 21(4): 97 – 102. http://.dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogrm.

- Etuk, S.J. & Ekanem, A.D. (2017). Socio-demographic and Reproductive Characteristics of women who default from orthodox obstetrics care in Calabar, Nigeria. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet; 73: 57-60.

- Awoyinka, B.S., Ayinde, O.A & Omigbodun, A.O. (2016). Acceptability of Caesarean delivery to Antenatal patients in a tertiary health facility in south west Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol.; 26(3); 208-210.

- United Nations – World Population Prospects: Akure, Nigeria Metro Area Population 1950-2023: -Akure – Historical Population Data https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/21978/akure/population; Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- Colton T., Statistics in Medicine. Little Brown & Co. 1974.

- Faremi, A., Ibitoye I., Olatubi M., Koledoye, P. & Ogbeye G. (2014). Attitude of pregnant women in south western Nigeria towards caesarean section as a method of birth. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol.;3(3):709-714. DOI: 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20140970.

- Robinson-Bassey, G. & Uchegbu, J. (2017). Perception and attitude of pregnant women towards caesarean section delivery in University Of Portharcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State. International Journal for Research in Health Sciences and Nursing, Volume-2, Issue-4.

- Orukwowu, U. & Ene-Peter, J. (2022). The Knowledge and Attitude of Pregnant Women towards Cesarean Section in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH). IPS Journalof Basic and Clinical Medicine, 1(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.54117/ijbcm.v1i3.3

- Al Sulamy, A. , Yousuf, S. & Thabet, H. (2019) Knowledge and Attitude of Pregnant Women toward Elective Cesarean Section in Saudi Arabia. Open Journal of Nursing, 9, 199-208. doi: 4236/ojn.2019.92020.

- Dorkenoo, J.E. & Abor, P.A. (2021). Pregnant women’s knowledge, perception and attitudes towards caesarian section among obstetrics unit attendants in a teaching hospital. Res. J. of Health Sci. Vol 9(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/rejhs.v9i3.2.

- Saoji, A., Nayse, J., Kasturwar, N. & Reiwani, N. (2017). Women’s knowledge, perception and potential demands towards caesarean section. National Journal of Community Medicine 2(2): 244-248.

- Nusrat, N., Nisar, A. S. & Ahson, M. (2019). Knowledge, attitude and preferences of pregnant women towards modes of delivery. Journal of Liaquat University of medical and Health Sciences, 8 (3): 228-233.

- Gamble, J.A. & Creedy, D.K. (2015). Women’s preference for a caesarean section: incidence and associated factors. Birth. 28(2):101-10.

- Dorkenoo, J.E. & Abor, P.A. (2021). Pregnant women’s knowledge, perception and attitudes towards caesarian section among obstetrics unit attendants in a teaching hospital. Res. J. of Health Sci. Vol 9(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/rejhs.v9i3.2.

- Sunday-Adeoye, I. & Kalu, C.A. (2011). Pregnant Nigerian women’s view of cesarean section Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice; 14(3), 276-279.

- Abah, M.G. & Umoh, A.V. (2015). Perception and attitude towards Caesarean section by pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in a Niger Delta tertiary facility. DOI: 10.47837/CMJ.19770126.201531167.

- Bam V, Lomotey AY, Kusi-Amponsah Diji A, Budu HI, Bamfo-Ennin D, Mireku G. Factors influencing decision-making to accept elective caesarean section: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2021 Aug 11;7(8):e07755. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07755. PMID: 34430742; PMCID: PMC8365447.

- Adewuyi, E.O., Auta, A. & Khanal, V. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Nigeria: A comparative study of rural and urban residences based on the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. PLoS One;13:e0197324.

- Ashimi, A.O., Amole, T.G. & Aliyu, L.D. (2013). Knowledge and attitude of pregnant Women to caesarean section in a semi-urban community in northwest Nigeria. Journal of the West African College of Surgeons; 3(2), 46-61.

- Afaya, R.A., Bam, V., Apiribu, F., Agana, V.A. & Afaya, A. (2018) Knowledge of Pregnant Women on Caesarean Section and their Preferred Mode of Delivery in Northern Ghana, NUMID HORIZON: An International Journal of Nursing and Midwifery,; 2(1), 62-73.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

THE IMPACT OF INTRODUCING A NURSING EDUCATION PROTOCOL ON THE INCIDENCE OF CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE INFECTIONS IN THE HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENT: A QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

Darija Knežević1*, Duška Jović1 & Miroslav Petković2

1. Department of Nursing, University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Medicine, Banja Luka, the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

2. Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Medicine, Banja Luka, the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

* Corresponding author: Darija Knežević, 1.Department of Nursing, University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Medicine, Banja Luka, the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. E-mail: darija.a.knezevic@med.unibl.org

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

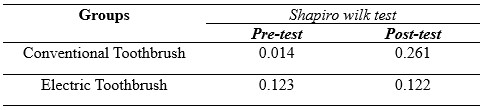

Introduction: Increased virulence of Clostridium difficile and use of antimicrobial drugs in recent years represent a challenge in the treatment of these infections in healthcare institutions. Improving the overall knowledge on prevention and control of C. difficile infections (CDI) among nurses may be one strategies to help reduce the CDI incidence rate in hospital settings.

Objective: The research objective was to develop, implement and evaluate a protocol for the prevention of CDI in hospital environment through nurses’ education.

Materials and Methods: This study utilized a quasi-experimental pretest–post-test design, which was carried out in tertiary care hospital, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The educational modules contained detailed description of prevention measures to prevent CDI transmission, and C. difficile toxins in faces were identified using laboratory enzyme immunoassays.

Results: The research included 60 nurses. There was a statistically significant difference (p=0.001) in the evaluation of knowledge in relation to professional experience and education level before the intervention. Nurses showed highly significant (p<0.001) better knowledge about C. difficile and CDI prevention on the test after the education. Before the education of nurses and technicians on preventive measures, CDI incidence was 11.04 per 10,000 patient – days, and after the education 6.49.

Conclusion: The study results showed that continuous medical education about CDI can have contribute to increasing knowledge and awareness about the importance of CDI prevention.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, infection, prevention, nurses, education.

INTRODUCTION