TRANSFORMATIVE LEADERSHIP AND JOB SATISFACTION IN THE NURSING PROFESSION: A NARRATIVE REVIEW

Carla Rizzo 1, Flavio Marti 2, Luca Perrozzi 3*, Lucia Mauro 4

- Complex Anesthesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care Unit, IRCCS Hospital Physiotherapy Institutes, Rome (Italy).

- Department of Health Professions AO San Camillo Forlanini, Master's Degree Course in Nursing and Midwifery Sciences, “Sapienza” University of Rome, San Camillo section, Rome (Italy).

- Accident and Emergency and Specialist Surgery Department, A.O. San Camillo Forlanini, Rome (Italy).

- Department of Surgical Sciences, Elective Surgery Block, A.O. San Camillo Forlanini, Rome (Italy).

*Corresponding Author: Luca Perrozzi, Department of Accident and Emergency and Specialist Surgery, Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo Forlanini, C.ne Gianicolense 87, 00159 Rome (Italy). Email: lucaperrozzi@yahoo.it

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Healthcare organisations require optimal leadership to achieve goals and deliver high-quality services. Leadership is the ability to influence employee behaviour and beliefs and is an essential element of a successful organisation. Improving job satisfaction is a key objective in addressing the challenges related to achieving and maintaining quality standards, ensuring patient satisfaction and staff retention. Similarly, transformational leadership has positive effects on nurses' job satisfaction and promotes organisational wellbeing in the workplace.

Objective: The purpose of the review is to describe transformational leadership and job satisfaction in the nursing profession through a narrative revision.

Materials and methods: The bibliographic research was carried out between September 2022 and March 2024 by consulting databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycInfo, with time limits of 12 years and Italian and English language filters. All items deemed relevant have been stored and managed with the Zotero IT platform.

Results: 16 studies were examined: 1 comparative study, 5 descriptive correlational studies, 1 meta-analysis, 1 systematic review, 4 cross-sectional studies, 2 mixed method studies and 2 unspecified studies. The results of this study are consistent with transformational leadership theory, which highlights the leader's role in providing employees with supportive work environments that result in higher levels of job satisfaction and efficiency.

Conclusions: The skills of a transformative leader, such as the ability to listen, provide support, and promote fairness and recognition, are fundamental to increasing nurses' job satisfaction and sustaining environments with a high level of quality of care. Healthcare managers must protect the quality of work undertaken by staff, implementing strategies that can improve nurses' working conditions.

Keywords: Transformational Leadership; Job Satisfaction; Nurse; Work environment.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare organisations are social systems in which human resources are the most important factor for the delivery of health care. Such organisations require optimal leadership to achieve goals and deliver high-quality services [1,2]. Leadership is the ability to influence employee attitudes and beliefs and is an essential element of successful and efficient organisations [3,4]. The current challenges of the health system require the presence of flexible and efficient managers [5] because the complexity of nurses' tasks requires complex leadership skills [6]. A wide range of studies have described the favourable outcomes of positive leadership, in particular, the transformational leadership style [7–9]. Transformational leadership motivates problem-solving and intellectual stimulation by influencing staff engagement in the organisation's mission. Such leaders stimulate nurses to use problem-solving strategies and provide patient care autonomously and responsibly [10]. Certain studies suggest that transformative leaders have positive effects on the wellbeing and job satisfaction of healthcare workers [4,11]. In addition, transformational leadership transforms nurses' goals and values for the benefit of the nursing profession [12] and work organisation and promotes team communication and collaboration, the work environment and organisational culture [13].

Work satisfaction, defined as “a pleasant emotional state that derives from the judgment of one's work or work experience” [14], is extremely important both for nursing managers and wellbeing of nurses in the workplace. Improving job satisfaction is a key objective in addressing the challenges related to achieving and maintaining quality standards, ensuring patient satisfaction and staff retention [15,16].

The more satisfied employees are, the more motivated they are to work and the greater the possibility of achieving the objectives, with an increase in productivity and quality. Job satisfaction cannot be overlooked if improving work performance is a priority of the organisation [17].

As part of the study, the authors described transformational leadership and staff job satisfaction, with the aim of synthesising the evidence that describes these aspects in the nursing profession.

Transformational leadership theorists indicate that leaders use socialised power to elevate and empower subordinates and provide the resources needed to achieve more than they thought possible in their work. Intrinsic motivation strategies support nursing autonomy, competence and relationship with others in the context of a mutually supportive environment to foster social and personal development at the service of the organisation's vision, mission, values, aims and objectives. In this way, subordinate nursing staff enjoy satisfaction in overcoming work challenges.

Nursing leaders must be proactive in recognising and addressing the job satisfaction needs of direct care nursing staff in order to maintain high-quality staff as well as the quality of patient care and healthcare environments [18].

Objective of the study

The purpose of the review is to describe transformational leadership and job satisfaction in the nursing profession through a narrative revision of the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

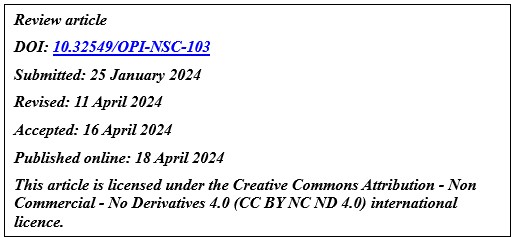

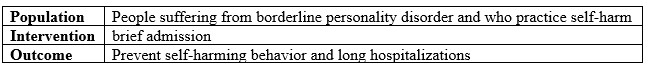

The bibliographic research was carried out from 1 September 2022 to 31 March 2024 by consulting the following databases: PubMed, Cinhal, and PsycInfo, with time limits of 10 years and Italian and English language filters. The research question was formulated according to the PICO method, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Research question formulated according to the PICO method

The following keywords were used: “transformational leadership”, “job satisfaction”, and “nurse*”. Within the study, all the articles that dealt with transformational leadership and job satisfaction in the nursing profession with a time limit of 12 years (from January 2012 to March 2024) were included in English and Italian. All articles written in other languages were excluded.

RESULTS

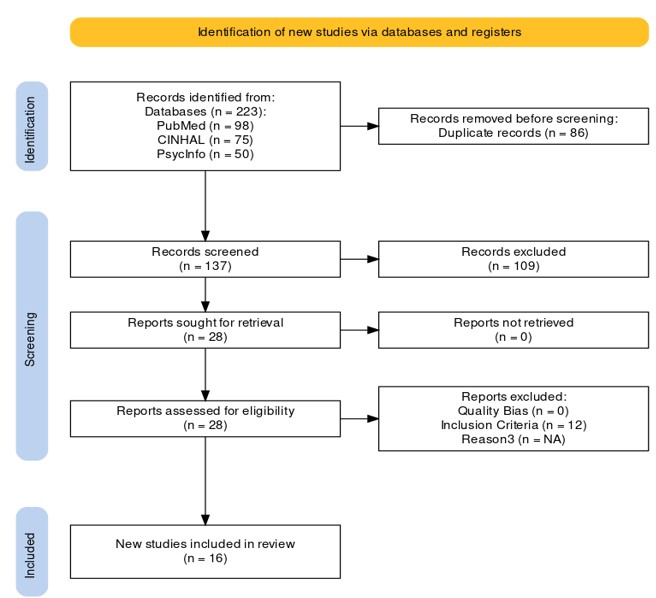

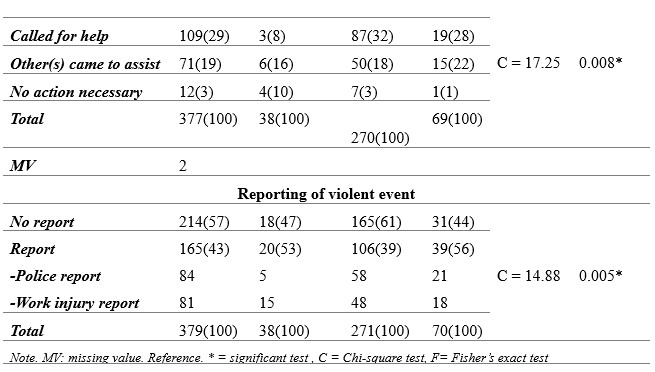

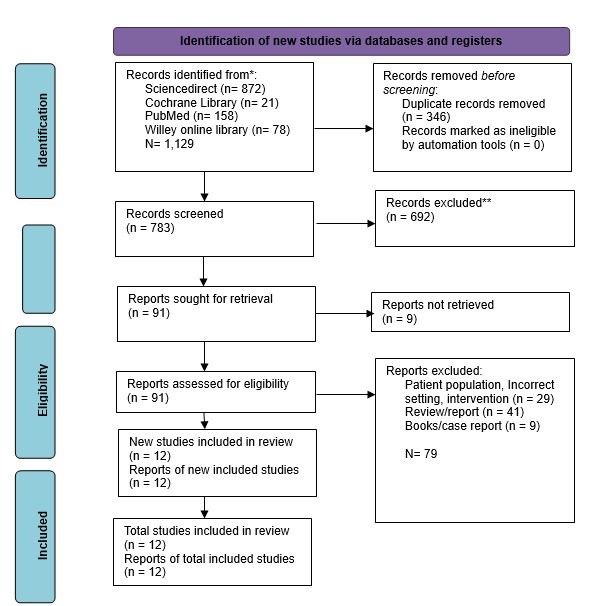

During the bibliographic research, the search string generated a listing of 223 articles on 3 different databases (PubMed, Cinhal, and PsycInfo) (figure 1).

Figure 1. “PRISMA Statement” flowchart[19].

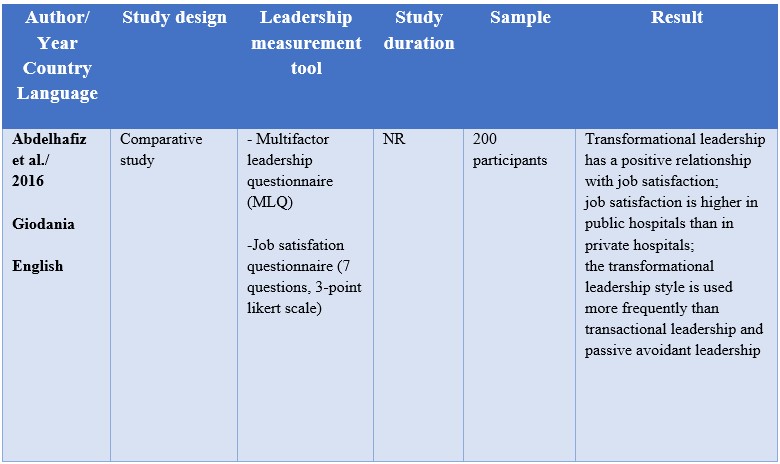

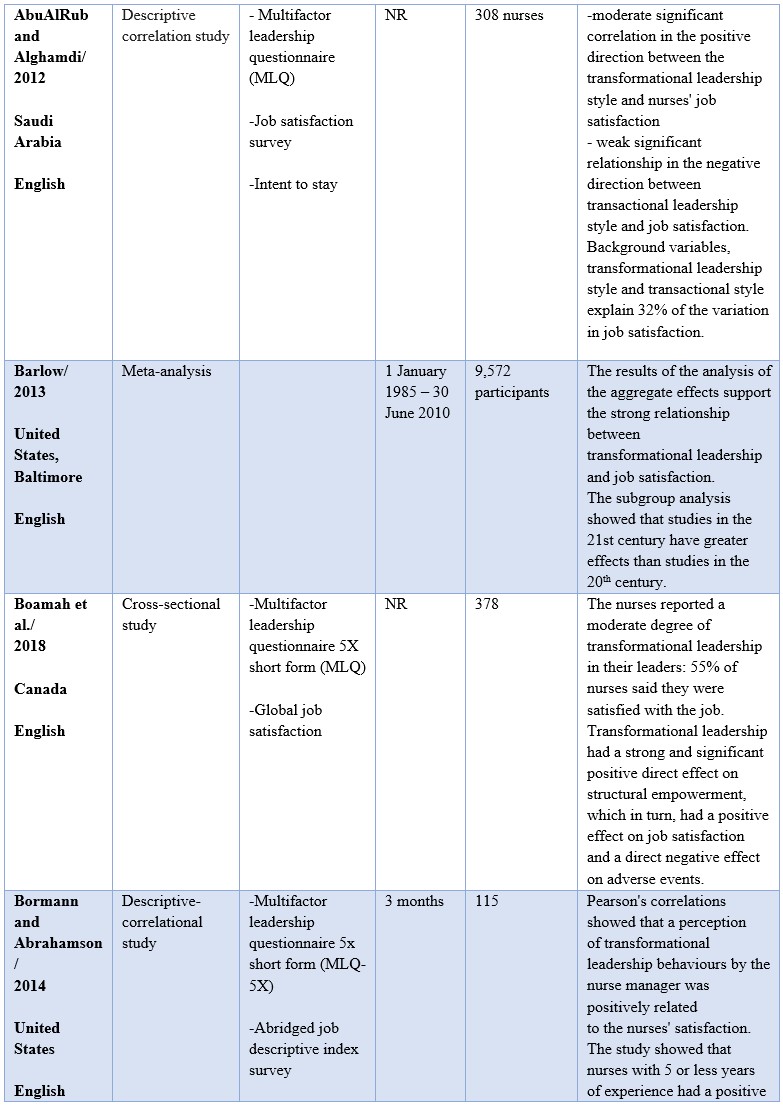

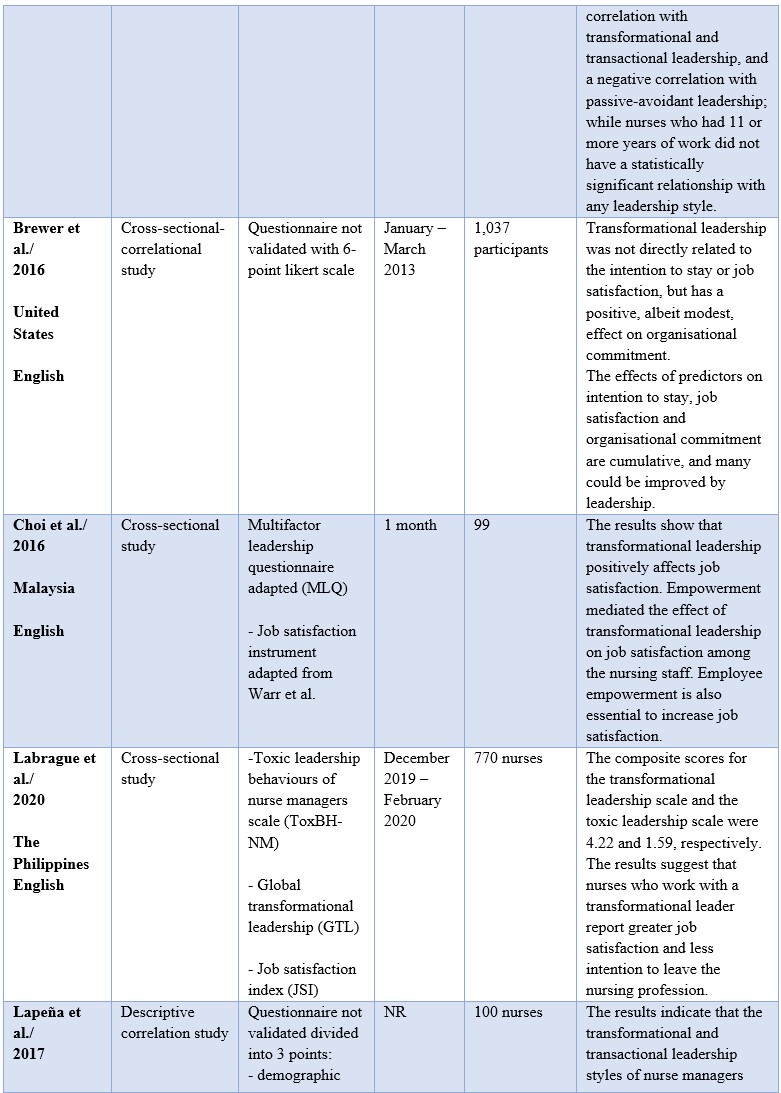

All items were managed using the Zotero IT platform. After the duplicates were removed, 137 articles remained. Selection by title and by abstract led to the exclusion of 109 articles. For the subsequent critical analysis, the 28 articles were read and evaluated in their entirety to identify and understand the content. On reading the full texts, 12 articles were discarded because they failed to comply with the inclusion criteria. A total of 16 studies were evaluated, broken down as follows: 1 comparative study, 5 descriptive correlational studies, 1 meta-analysis, 1 systematic review, 4 cross-sectional studies, 2 mixed method studies, 2 unspecified studies (see Table 2). Fifteen articles were published in English and one in Italian.

Evaluation of the quality of the studies

The articles were selected and evaluated using the checklists from “JBI Critical Appraisal Tools” [20]. A total of 16 articles were reviewed. To classify the studies in terms of quality, the overall score was calculated based on the number of "yes" answers. The included studies had at least 6 out of 10 of the items included in the checklists chosen by the authors of this study.

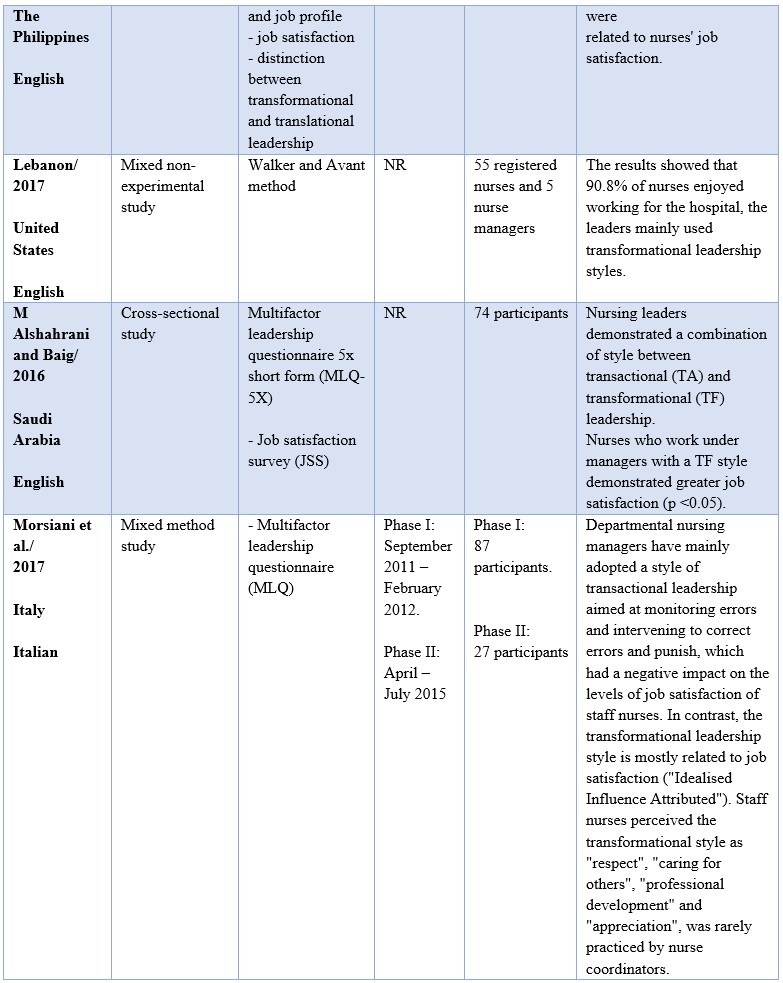

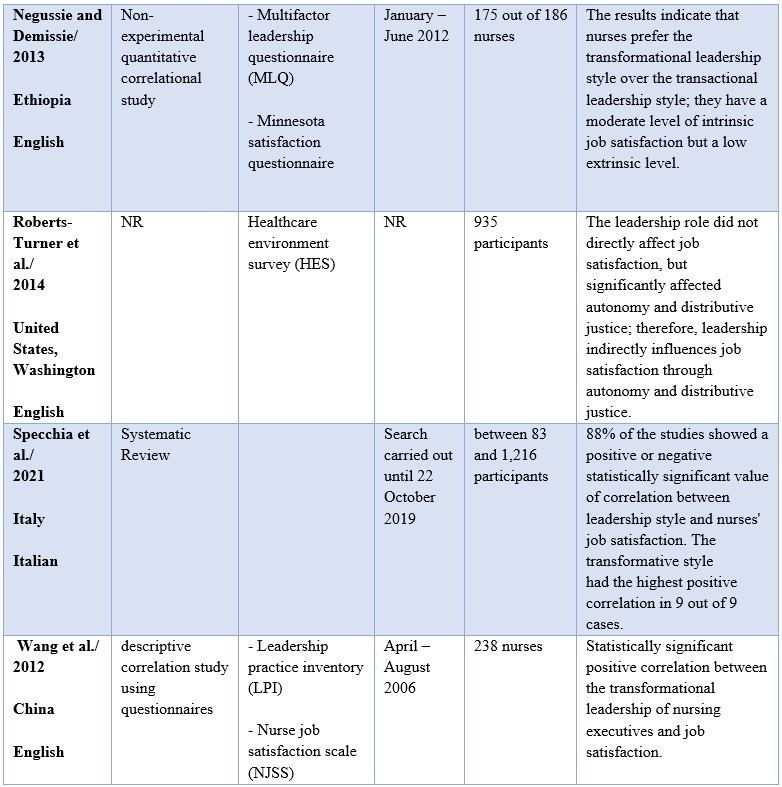

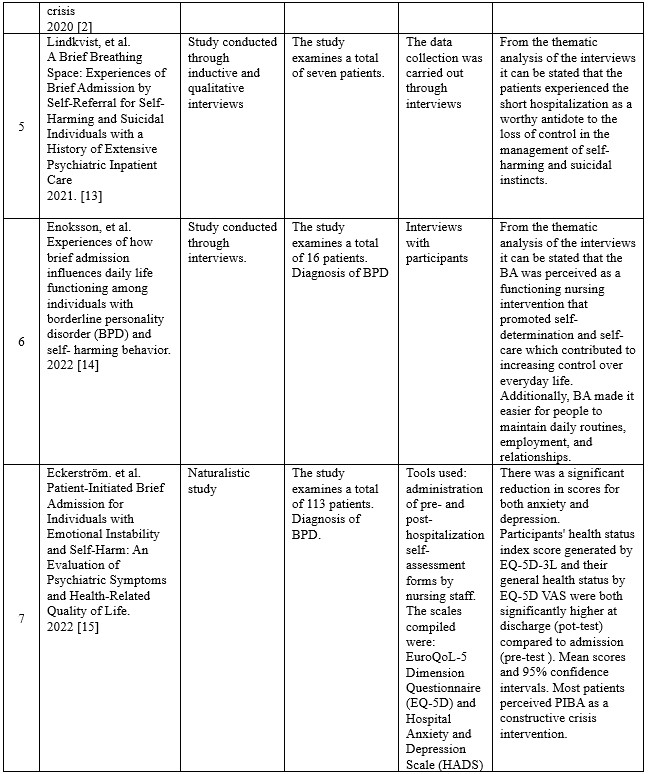

Table 2. Summary of results

DISCUSSION

The literature considered demonstrates that the transformational leadership style can positively influence job satisfaction in most of the included studies, regardless of the sample, the country, or the type of study chosen [21–34]. Only two studies do not describe a positive link between the variables analysed [35,36].

The results of this review highlight that the characteristics of a transformative leader – such as listening, support, fairness and recognition – are fundamental to increasing nurses' job satisfaction and creating environments with superior quality of care.

For example, the results of the systematic review by Specchia [31] and AbuAlRub and Alghamdi [34] emphasise that leaders who adopt a transformative style promote greater job satisfaction among nursing staff than those who adopt a transactional style. In fact, transformational leadership shows a significant and moderate correlation with job satisfaction (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), while transactional leadership shows a weak significant relationship with job satisfaction (r = -0.14, p < 0.01)[34]. In fact, the strength of transformational leaders is that they dedicate time to teaching and coaching nurses, focus on developing and improving their strengths, and provide advice for their professional and personal development [31].

These results are consistent with previous studies by Al-Hussami [37] and Bass [38]. These studies support the idea that nurses who worked with leaders who showed transformational leadership styles were more satisfied. In fact, these leaders taught and trained nurses, providing advice for professional development, treating them as individuals, listening to their concerns, and promoting their personal development[39].

Another issue concerns the correlation between transformational leadership, job satisfaction and the intention to leave work. For example, Labrague's study [26] shows how the transformational leadership of nursing executives influences nurses' job satisfaction and their intention to leave the profession despite the demographic characteristics (age, sex, sentimental situation, full time). Specifically, it differentiates toxic leadership from transformational leadership. Toxic leadership is significantly correlated with dissatisfaction at work (r = -0.19, p <0.001), absenteeism (r = 0.23, p < 0.001), psychological distress (r = 0.09, p < 0.05), organisational turnover intention (r = 0.11, p < 0.01) and professional turnover intention (r = 0.14, p < 0.001). Instead, transformational leadership is significantly related to job satisfaction (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), absenteeism (r = -0.13, p < 0.001) and the intention of organisational turnover (r = -0.08, p < 0.05). This underlines how important it is to educate leaders and nurse managers within healthcare facilities and develop behaviours that help and support staff. Indeed, maintaining a quality working environment has a significant impact on the retention of nurses and decreases the intention to leave the profession or nurse turnover.

In contrast, the results of the study by AbuAlRub and Alghamdi [34] indicate that the relationship between the transformational leadership style and the level of intention to stay at work was not statistically significant (r = 0.08, p = 0.14), so the transformational leadership style had no effect on the intention to stay at work.

Even if the results regarding intention to leave the profession are mixed, transformational leadership can provide supportive work environments that result in higher levels of job satisfaction and effectiveness [39]. In fact, by strengthening solid relationships with staff, transformational leaders understand the needs of nurses, they encourage staff to develop skills and autonomy in order to empower them to act.

The studies by Bohaman [23] and Choi [25] analysed the role that structural empowerment has in the relationship between job satisfaction and the transformational leadership style. Structural empowerment, in line with other previous research, [40–42] influences job satisfaction, organisational commitment[41], work commitment[43], lower levels of burnout and work stress [41] and turnover intentions[41,44]. This is due to the characteristics of the transformational leader, such as the ability to listen, inspire staff and stimulate individual and group skills. We can therefore state from these studies [23,25] that empowerment has a positive influence on job satisfaction.

In the study by Borman and Abrahamson [24], it emerged that nurses who worked for 5 or fewer years within the hospital had a statistically positive correlation with transformational and transactional leadership, while nurses who worked for 11 or more years did not have any type of significant relationship with any leadership style. For those who worked for 5 or fewer years, job satisfaction was mainly related to promotion opportunities, while for nursing staff of 11 or more years it had a stronger correlation for supervision. Therefore, leaders must understand the needs of their employees based on individual differences and their work experience.

The studies by McVicar and Laschinger [35,36] did not find a direct correlation between transformational leadership and job satisfaction. Roberts and Turner [36] highlighted how autonomy and distributive justice positively affect job satisfaction (0.503, p < 0.001; 0.272, p < 0.001). Within the study, the authors emphasise that autonomy represents a characteristic of transformational leadership, and distributive justice represents transactional leadership. It follows that, even if a direct relationship between the variables considered has not been found, autonomy represents one of the fundamental characteristics of the transformational leadership style. This implies that an increase in autonomy and distributive justice would increase job satisfaction.

Conversely, according to Brewer,[35] transformational leadership was not a significant predictor of job satisfaction. The variables with positive significant coefficients related to job satisfaction were organisational commitment, autonomy, tutor support and promotional opportunities. Considering job satisfaction as a dependent variable, a nurse who goes from a low organisational commitment value to a very high organisational commitment value is 12.6% more likely to be satisfied.

The Barlow meta-analysis [22] showed a very strong relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction: the aggregate result of the studies generated by the estimates of the size of the effect are more incisive and representative than the outcomes of individual studies examined. The study shows how transformational leaders stimulate and empower nurses to provide the resources needed to achieve greater results. In fact, staff intrinsic motivation strategies support autonomy, competence, and nursing relationships to create a mutually supportive work environment that promotes social and individual development at the service of the organisation's mission, values, and goals. In addition, the results report that the relationship between transformational leadership/job satisfaction has strengthened over time. The subgroup analysis showed that studies in the 21st century have stronger effects than studies in the 20th century. This can be explained by the identification of the Magnet design health and nursing excellence programmes, which notably increased in the 21st century [22]. Therefore, strategies must be implemented within hospitals today to increase the job satisfaction of nurses by assessing staff satisfaction on an annual basis and improving working conditions.

Another result to consider concerns the difference reported in various studies within the Barlow meta-analysis [45–47] between the greater satisfaction detected by nurses in indirect or mixed care (nurse administrators, specialised nurses) compared to staff engaged in direct care (ward nurses). This can be explained by the great shortage of nurses that is being experienced worldwide, which leads to greater workloads, work stress, burnout, intentions to leave the profession and turnovers that strongly affect job satisfaction. This is why nursing leaders are fundamental in order to understand and recognise the needs of their staff, to maintain a high quality of work, as direct care provides essential services for patients.

A study conducted in Italy by Morsiani[29] engaged focus groups to identify the main characteristics of a leader in relation to the achievement of satisfaction:

- Professional recognition. Job satisfaction depends on professional recognition, that is, giving value to the work of a nurse and expressing appreciation for the work of the staff.

- Fairness. Nursing leaders must adopt the same behaviour, be honest with all staff members and be objective about mistakes at work.

- Care of the individual. If a leader supports and listens to their staff, the latter will be more likely to experience job satisfaction. Often, the role of nurses, especially in Italy, is not recognised at a social and economic level. The first in the field who must defend the profession are precisely the leaders who must lead the profession to its emancipation, while maintaining relationships with other professionals. In fact, it is not a war between professions but an endeavour to enhance the value of the nursing profession.

- Support. Globally, the shortage of nurses impacts patient care, as the same care result must be achieved in the same time and with fewer human and material resources. Leaders should not put themselves on a different plane than nurses but should be present in the ward and help them in case of need. In addition, being present in the department is an opportunity to check the work of the staff and recognise what the errors may be within the care path and look for strategies to improve it.

- Listening. Being present also means knowing how to listen and understand the needs of the staff, such as shift scheduling and the difficulties encountered at work.

- Staff appreciation. The nursing manager must promote staff development by seeking to improve nurses, both individually and as a group. Training, feedback, and refresher courses are crucial tools to ensure that staff have greater autonomy and responsibility.

- Team development. Another important issue is teamwork. This study revealed the extent to which staff did not feel part of a work group. Teamwork is essential to ensuring collaboration, compensating for others' inadequacies, and sharing common goals and strategies to achieve patient satisfaction.

Therefore, there is scope for future studies employing a more rigorous research approach that would establish causal links between the variables considered and the appropriateness of generalising the results.

CONCLUSIONS

The review found that transformational leadership can have a positive influence on nursing job satisfaction levels. Therefore, nursing leadership assumes a fundamental role in influencing the perception that nurses have of their organisation. A leadership style that promotes nurses' autonomy, support, and empowerment can improve job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and nurses' intention to remain in their position while reducing emotional exhaustion [6]. This means that transformational leaders, through their stimulating and motivating behaviour, can induce changes in the psychological states of workers within organisations. In addition, some studies have shown how the adoption of the transformational leadership style can indirectly influence job satisfaction through the development and strengthening of nurses' sense of empowerment [23,25]. Within healthcare organisations, leadership plays a key role in providing effective and efficient care and translates into positive outcomes for professionals, patients and the work environment. It is therefore necessary to identify and fill the current gaps in the skills and abilities of nursing leaders through educational activities in institutions, underlining the importance of a two-way communication process and mutual trust between managers and nursing staff. The purpose of the review was to offer an overview of a current topic, as both job satisfaction and transformational leadership are two fundamental issues for the creation of a healthy and efficient work environment. Despite the fact that leadership quality and job satisfaction can be assessed using proven and generalizable measurement tools, few studies adopt such methods, and they thus fail to draw conclusions from the relationship between pertinent variables. For the future, the authors suggest conducting studies that can correlate transformational leadership and job satisfaction to obtain more generalizable results because these issues are based much more on empirical experience than on robust scientific evidence.

Limitations of the study

Although the research met the objective of this study, the review has limitations. For example, one of the limitations of a narrative review concerns the methodology itself; whereas a systematic review has a clear and obligatory a priori methodology, the narrative review approach lacks a research protocol. Another limitation is the interpretation bias of the results, which can bring to light only a part of the chosen topic. To confirm what has been described in this review, other studies are needed that can obtain certain, reproducible and generalizable results. In addition, the results that emerged from the other studies were evaluated by means of self-assessment questionnaires, which are frequently associated with response bias.

Funding

This study did not receive any form of funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this study.

REFERENCES

[1] Huber D. Leadership and Nursing Care Management. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia PA: 2006.

[2] Frisicale EM, Grossi A, Ccacciatore P, Carini E, Villani L, Pezzullo AM, et al. The need of leadership in managing healthcare and policy-making - G. Ital. Health Technol. Assess. 2019.

[3] Cleary M, Horsfall J, Jackson D, Muthulakshmi P, Hunt GE. Recent graduate nurse views of nursing, work and leadership. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2904–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12230.

[4] Mannix J, Wilkes L, Daly J. ‘Watching an artist at work’: aesthetic leadership in clinical nursing workplaces. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:3511–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12956.

[5] Casida J, Parker J. Staff nurse perceptions of nurse manager leadership styles and outcomes: Nurse manager leadership styles and outcomes. J Nurs Manag 2011;19:478–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01252.x.

[6] Laschinger HKS, Wong CA, Cummings GG, Grau AL. Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: the value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nurs Econ 2014;32:5–15, 44; quiz 16.

[7] Al-Yami M, Galdas P, Watson R. Leadership style and organisational commitment among nursing staff in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Manag 2018;26:531–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12578.

[8] Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S, Wong CA, Paananen T, Micaroni SPM, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;85:19–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.016.

[9] Umrani WA, Afsar B. How transformational leadership impacts innovative work behaviour among nurses. Br J Healthc Manag 2019;25:1–16. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2018.0069.

[10] Madathil R, Heck NC, Schuldberg D. Burnout in Psychiatric Nursing: Examining the Interplay of Autonomy, Leadership Style, and Depressive Symptoms. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2014;28:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2014.01.002.

[11] Robbins B, Davidhizar R. Transformational Leadership in Health Care Today. Health Care Manag 2020;39:117–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCM.0000000000000296.

[12] Lievens I, Vlerick P. Transformational leadership and safety performance among nurses: the mediating role of knowledge-related job characteristics. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:651–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12229.

[13] Spies LA, Gray J, Opollo JG, Mbalinda S, Nabirye R, Asher CA. Transformational leadership as a framework for nurse education about hypertension in Uganda. Nurse Educ Today 2018;64:172–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.02.009.

[14] Locke EA. “Job satisfaction reconsidered”: Reconsidered. Am Psychol 1978;33:854–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.33.9.854.

[15] De Simone S, Planta A, Cicotto G. Il ruolo delle capacità agentiche nelle intenzioni di turnover del personale infermieristico 2018.

[16] Khamisa N, Oldenburg B, Peltzer K, Ilic D. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:652–66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120100652.

[17] Yang F-H, Wu M, Chang C-C, Chien Y. Elucidating the Relationships among Transformational Leadership, Job Satisfaction, Commitment Foci and Commitment Bases in the Public Sector. Public Pers Manag 2011;40:265–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102601104000306.

[18] Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2008;38:223–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7.

[19] Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev 2022;18:e1230. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1230.

[20] Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2019;Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099.

[21] Abdelhafiz IM, Alloubani AM, Almatari M. Impact of leadership styles adopted by head nurses on job satisfaction: a comparative study between governmental and private hospitals in Jordan. J Nurs Manag 2016;24:384–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12333.

[22] Barlow KM. A Meta-Analysis of Transformational Leadership and Subordinate Nursing Personnel Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intentions. University of Maryland, Baltimore, 2013.

[23] Boamah SA, Spence Laschinger HK, Wong C, Clarke S. Effect of transformational leadership on job satisfaction and patient safety outcomes. Nurs Outlook 2018;66:180–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2017.10.004.

[24] Borman e Abrahason. Do staff nurse perceptions of nurse leadership behaviors influence staff nurse job satisfaction? The case of a hospital applying for Magnet® designation. J Nurs Adm 2014;44:219–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000053.

[25] Choi SL, Goh CF, Adam MBH, Tan OK. Transformational leadership, empowerment, and job satisfaction: the mediating role of employee empowerment. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0171-2.

[26] Labrague LJ, Nwafor CE, Tsaras K. Influence of toxic and transformational leadership practices on nurses’ job satisfaction, job stress, absenteeism and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:1104–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13053.

[27] Lapeña LFR, Tuppal CP, Loo BGK, Abe KHC. Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot Study. Nurse Media J Nurs 2017;7:65–78.

[28] Libano MC. Registered Nurse Job Satisfaction and Nursing Leadership. Regist Nurse Job Satisf Nurs Leadersh 2017:1–1.

[29] Morsiani G, Bagnasco A, Sasso L. How staff nurses perceive the impact of nurse managers’ leadership style in terms of job satisfaction: a mixed method study. J Nurs Manag 2017;25:119–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12448.

[30] Negussie N, Demissie A. Relationship between leadership styles of nurse managers and nurses’ job satisfaction in Jimma University Specialized Hospital. Ethiop J Health Sci 2013;23:49–58.

[31] Specchia ML, Cozzolino MR, Carini E, Di Pilla A, Galletti C, Ricciardi W, et al. Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Results of a Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041552.

[32] Wang X, Chontawan R, Nantsupawat R. Transformational leadership: effect on the job satisfaction of Registered Nurses in a hospital in China. J Adv Nurs John Wiley Sons Inc 2012;68:444–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05762.x.

[33] Alshahrani FM, Baig LA. Effect of Leadership Styles on Job Satisfaction Among Critical Care Nurses in Aseer, Saudi Arabia. J Coll Physicians Surg--Pak JCPSP 2016;26:366–70.

[34] AbuAlRub RF, Alghamdi MG. The impact of leadership styles on nurses’ satisfaction and intention to stay among Saudi nurses. J Nurs Manag 2012;20:668–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01320.x.

[35] Brewer CS, Kovner CT, Djukic M, Fatehi F, Greene W, Chacko TP, et al. Impact of transformational leadership on nurse work outcomes. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:2879–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13055.

[36] Roberts-Turner R, Hinds PS, Nelson J, Pryor J, Robinson NC, Wang J. Effects of leadership characteristics on pediatric registered nurses’ job satisfaction. Pediatr Nurs 2014;40:236–41, 256.

[37] Al-Hussami M. Study of nurses’ job satisfaction: The relationship to organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and level of education. Eur J Sci Res 2008;22:286–95.

[38] Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Developing Transformational Leadership: 1992 and Beyond. J Eur Ind Train 1990;14. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090599010135122.

[39] Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Manual and sample set (3rd ed.). 3rd ed. 2004.

[40] Lautizi M, Laschinger HKS, Ravazzolo S. Workplace empowerment, job satisfaction and job stress among Italian mental health nurses: an exploratory study. J Nurs Manag 2009;17:446–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00984.x.

[41] Spence Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Wilk P. Context Matters: The Impact of Unit Leadership and Empowerment on Nurses’ Organizational Commitment. JONA J Nurs Adm 2009;39:228–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23d2b.

[42] Pineau Stam LM, Spence Laschinger HK, Regan S, Wong CA. The influence of personal and workplace resources on new graduate nurses’ job satisfaction. J Nurs Manag 2015;23:190–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12113.

[43] Boamah S, Laschinger H. Engaging new nurses: the role of psychological capital and workplace empowerment. J Res Nurs 2015;20:265–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987114527302.

[44] Cai C, Zhou Z. Structural empowerment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of Chinese clinical nurses. Nurs Health Sci 2009;11:397–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00470.x.

[45] Tellez M. Work satisfaction among California registered nurses: a longitudinal comparative analysis. Nurs Econ 2012;30:73–81.

[46] Çelik S, Hisar F. The influence of the professionalism behaviour of nurses working in health institutions on job satisfaction: Professionalism behaviour of nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 2012;18:180–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02019.x.

[47] Ingersoll GL, Olsan T, Drew-Cates J, DeVinney BC, Davies J. Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Career Intent: JONA J Nurs Adm 2002;32:250–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200205000-00005.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Patients’ preferences, feelings, and benefits on Music-Based Intervention: A Pilot Study in COVID-19 Hospitalization

Alessio Pesce 1, Francesca Lantieri 2

- Department of Internal Medicine, Local Health Authority ASL2, Savona (Italy)

- Department of Health Science, Biostatistics Unit, University of Genoa, (Italy)

* Corresponding author: Dr. Alessio Pesce, Department of Internal Medicine, Local Health Authority ASL2, Savona (Italy), Piazza Sandro Pertini n. 10, 17100 Savona, Italy.

Email: alessio.pesce@uniupo.it, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2702-4101

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: COVID-19 patients survive in isolation with stringent measures of infection containment, leading to anxiety, fear, stress, loneliness, and depression. Music is recognized as useful to promote multiple health outcomes, including anxiolytic effects, pain-relieving, and relaxing effects that favour well-being and social interaction in healthcare settings.

Objective: This study aimed to determine the impact of a pre-recorded music-based intervention on the music perception in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Music appreciation, evoked emotions, and self-reported effects were explored and compared before and after music-based intervention, also considering the gender of the patients.

Methods: This prospective study consisted of a pre-recorded music-based intervention administered to 272 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 by piping the music into rooms of inpatient medical area. Pre-recorded musical pieces of were selected by a music therapist considering specific formal and parametric characteristics, with the purposes of distraction, entertainment, relaxation, and emotional support. The patients’ opinions were collected using an ad hoc self-report questionnaire and a short data survey that followed the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) guidelines.

Results: Music resulted to be the preferred entertainment activity during hospitalization by 84.6% of patients, with 96.6% of them expecting a positive effect and a very high grade of usefulness attributed to music before hospitalization and even higher afterwards. The music intervention significantly changed the patients’ perception of music from everyday life to hospitalization (p<0.0001). It proved successful in evoking pleasure and fun, which raised from 18.4% of everyday life to 41.1% during hospitalization. The usefulness of listening music to alleviate unpleasant feelings including anxiety, fear, loneliness, and low mood in COVID-19 disease, had a significant increase from 22.5% to 60.0% after the music intervention.

Conclusion: Music-based intervention, directed according to reference frameworks, provides self-reported social and emotional support in hospitalized patients for COVID-19.

Keywords: Covid-19, music therapy, emotions, hospitalization, music medicine

INTRODUCTION

Music represents an interdisciplinary topic, transversal to medicine and the human sciences. It constitutes a non-pharmacological intervention aimed at multiple health outcomes, including anxiolytic, pain-relieving, and relaxing effects that promote well-being, sleep quality and social interaction in healthcare settings [1-7]. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 survive in isolation with stringent infection containment measures, which lead to anxiety, fear, stress, loneliness, and depression, even to the point of evoking obsessive thoughts; in the most severe cases they compromise the prognosis, increasing mortality and adverse events. Music-based interventions, therefore, can also be used in psycho-social need in COVID-19 patients [1]. To date, research protocols are available in the hypothesis that music can reduce anxiety, depression or improve the quality of life in COVID-19 patients [8]. Therefore, studies to explore patients’ perspectives and determine the effects of music-based intervention during hospitalization are needed to provide scientific evidence. Some authors [9] remark how essential the compatibility of musical pieces with people’s preferences is and how these may vary depending on expectations at a specific moment, health conditions, or the healthcare environment. A crucial aspect in music-based interventions is the proper selection of musical pieces. Listening to specific types/genres of favorite music or sounds is likely to have an emotional impact based on patients’ clinical conditions. Systematic reviews show that patients’ music background and listening habits have been drastically underestimated, reported in only 7.7% of the studies conducted [10]. Only about 25% of studies have explored patient feedback on musical [10]. Personality plasticity, cognitive-affective components [11] and the clinical conditions of patients, especially respiratory system efficiency and symptom aggravation, show a close correlation with music preferences [9], stated even before COVID-19 disease. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the in-patients’ music preferences, the utility that listening to music might have for them, and their feelings also in relation to COVID-19 before starting a music-based intervention. This knowledge would allow health and music professionals to personalize the intervention and be able to demonstrate important correlations between habitual musical preferences and attitudes with those experienced by the patient as a result of listening to music. The literature generally admits methodological weaknesses in music-based interventions [10,12]. There is a lack of scientific rigor in music selection, in the involvement of music experts, and in reporting and describing the music pieces used [12]. Furthermore, music has rarely been selected to achieve specific effects according to the reference frameworks [10,12]. The opportunity to identify music mechanisms of action would allow researchers to advance beyond basic questions about efficacy and begin to answer questions about how, why, and for whom an intervention works [12]. For these reasons, we applied a music-based intervention to in-patients affected by COVID-19 after pre-inquiring their music preferences and have administered a questionnaire to investigate their appreciation for music both before and after the intervention. The music-based intervention was selected by a music therapist and integrated according to guidelines and [13] a consolidated framework [14].

Objective

This study aimed to determine the impact of a pre-recorded music-based intervention on the music perception in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Music appreciation, evoked emotions, and self-reported effects were explored and compared before and after the music-based intervention, also considering the gender of the patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Recruitment and Clinical Setting

All adult patients with COVID19 admitted to the COVID-19 inpatient medical area of the Italian hospital Santa Maria Misericordia (Local Health Authority ASL2, Savona), between May 18, 2020 and February 18, 2022 were recruited. The inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older, ability to understand, write and speak Italian, and written consent to the study. Patients with severe hearing and visual deficits, and with alterations of the state of consciousness, as assessed by the medical-nursing staff, were excluded. No exclusion criteria based on covid severity were applied. According to Italian rules at that period, no COVID-19 patient received visits from friends or family members during hospitalization. The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee (May 18, 2020 – Protocol Number 10459); informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Study Design

This prospective study consisted of a pre-recorded music-based intervention and the administration of a questionnaire aimed at determining the perception of music in patients hospitalised for COVID-19, and their point of view on music listening in terms of their attitude toward music and the set of sensation associated to listening the music, during hospitalization, before and after the music intervention. Patients, upon their acceptance to participate in the study, were received an ad hoc self-report questionnaire and a short data survey, both in paper form. The questionnaire included 15 pre-treatment questions regarding the patients’ attitude toward music in their everyday life and in the hospital setting and 3 post-treatment questions to be answered after the music treatment. The patients were instructed to fill in in only the pre-intervention questions before the music treatment and to complete the rest of the forms only after the music intervention. The afternoon following admission, a single 90-minute length music-based intervention was introduced in the in-patient rooms via piped music. On the same day, following the musical presentation, the two data sheets were collected. Patients who agreed to participate to the study but refused the music-based intervention due to their choice or clinical worsening, were still invited to fill in Q1-Q15 and short data record at their convenience or after the improvement of their health conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

Criteria for constructing the questionnaire

The present questionnaire was specifically constructed for this study to explore preferences, diffusion modes, utility, emotions evoked, and self-reported effects, also considering the gender, and to compare the point of view during hospitalization with what described by the patient after the music-based intervention. A preliminary questionnaire was constructed in 2013 and used for the first time on a sample of 55 patients to evaluate the point of view on habitual music listening and in hospitalization for cardiac catheterization [15]. The meaningful constructs, facade preferences and response categories that emerged from this previous study guided the initial design of the items for the present study. Based on this, an updated questionnaire was developed in 2020 following the adoption of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to integrate a music-based intervention. According to the CFIR framework, to embody music into the hospitalization through piped music, it is necessary to explore the possibility of integrating music into the in-patient setting.

The purpose was to 1) understand the general appreciation and practical feasibility of the musical introduction, 2) explore the point of view of operators and patients to define the modalities of integration in the healthcare setting and 3) investigate listening preferences before the experimentation. To this aim, the updated questionnaire, preliminary to the present one, was submitted to all the 33 healthcare professionals and to a limited sample of 25 patients before the start of the experimentation. They were asked to give their opinion on the questionnaire and fill in two short surveys to assess the overall comprehensibility of the questionnaire and collect the suggestions from patients and health professionals, aimed at improving the form and content of the questionnaire. Based on scientific evidence from the literature [1-7,10,12], the frameworks on music selection, and the suggestions that had emerged from patients and operators in the preliminary investigation, the final questionnaire was declined and then submitted to the different sample of 267 patients of the present study, together with the short survey. The final questionnaire, specifically constructed for this study, consists of 18 questions. The questionnaire is structured in two sections, the first, pre-intervention, with the aim of exploring the patient’s habitual (8 questions, T0) and hospitalization perceptions (7 questions, T1) and the second to explore the patient’s experience after the music-based intervention (3 questions, T2). For questions 1 to 18 the participants can choose one of the predefined answers that best describes his or her point of view, with the possibility, for eleven of these questions, to enter open answers different from the predefined ones. Socio-demographic data (nationality, sex) were collected by the short data survey that was administered by a separate sheet and that include the overall evaluation of the questionnaire by the participant. This short survey also includes the pre-post opinions about the music intervention through 5 Point Likert Scale Questions (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neither agree nor disagree, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree).

Intervention

A pre-recorded music-based intervention was developed in the pre-experimental phase when the preliminary version of the questionnaire was developed. During this phase, musical genres of patients’ preference on admission were explored. A music therapist structured an intervention based on the opinions of 25 patients. The music-based experimentation was designed using specific theoretical frameworks for music selection [10] and reporting intervention quality guidelines [13]. Pre-recorded pieces of music were selected considering specific formal and parametric characteristics with the purposes of distraction, entertainment, relaxation, and emotional support. The selection criteria, declined through the intervention reporting checklists by Robb SL et al. [13] reported on the Equator Network are detailed in Table 1. The piped music was transmitted into the single room of patient participating to the study via a player and an amplifier located in a workstation isolated from the COVID-19 wards. Ceiling speakers were used to prevent contamination through portable music players/earphones and in consideration of the poor management of portable devices or musical instruments due to medical ventilation devices.

Table 1. Music-Based Intervention

Statistical Analysis

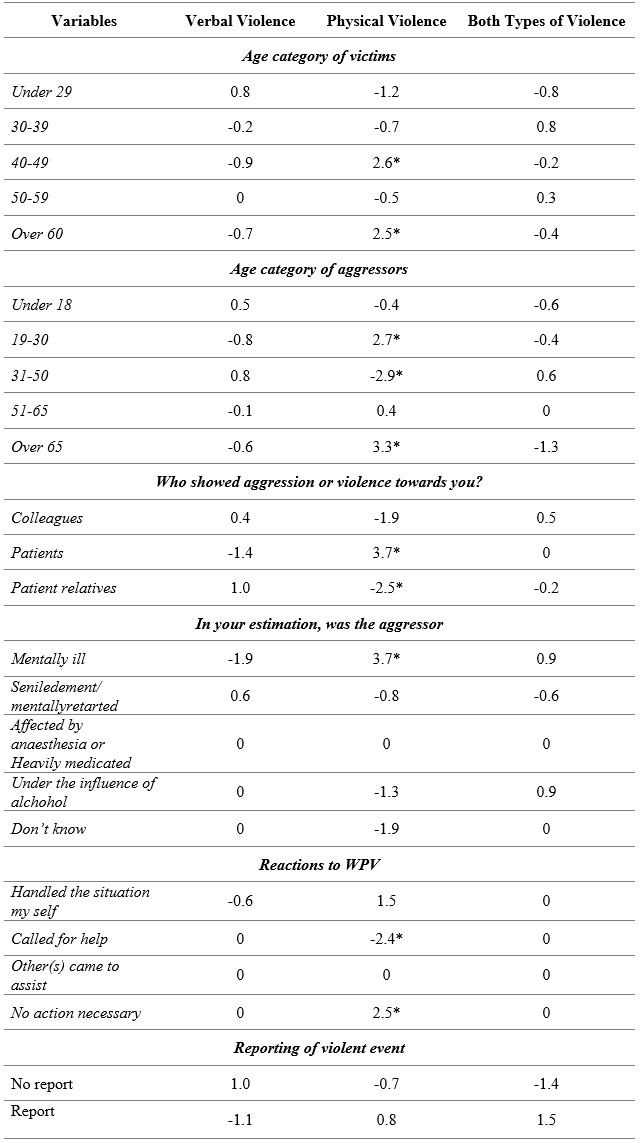

Categorical data are reported as counts (N) and percentages (%) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI, binomial exact calculation). We applied the Cramer’s V test to investigate if the usually preferred genre of music (classical, Italian, foreign language, etc.) correlated with the preferences during hospitalization (Q3 vs Q13). Categorical variants were compared by Chi-square test or by Fisher’s exact test when more appropriate. In particular, the Fisher’s exact test was applied to explore if the emotional effects (relaxation, happiness, crave, etc.) were different between what expected in usual settings and what was expected during hospitalization (Q8 vs Q17). The Fisher exact test was also used to compare if patients enjoyed music and the reasons why they listened to music (the utility of the music in terms of kind of sensations achieved: amusement, relief, etc.) in the three settings: usual life vs what expected during hospitalization vs what actually felt during hospitalization (Q1 vs Q14 vs Q16, and Q7 vs Q12 vs Q18, respectively). These tests were confirmed by the Cochrane Q test to compare more than two groups for a binary outcome when considering only the two categorical “yes” or “no” answers. Also, the differences between females and males were investigated through the Fisher’s exact test, as well as the association between the genre of music preferred during the hospitalization and the emotional effect and the utility in terms of sensation achievement. Finally, the level of appreciation of music measured by the Likert questions was compared before and after the music intervention by the Wilcoxon test, while the correlation was estimated by Spearman’s rho; the differences between males and females were tested by the Mann-Whitney test. All tests were two tailed and considered significant with p-value (p) <0.05. Data were analyzed using 24.0 SPSS Software.

RESULTS

Analyzed Sample and Baseline patients’ characteristics

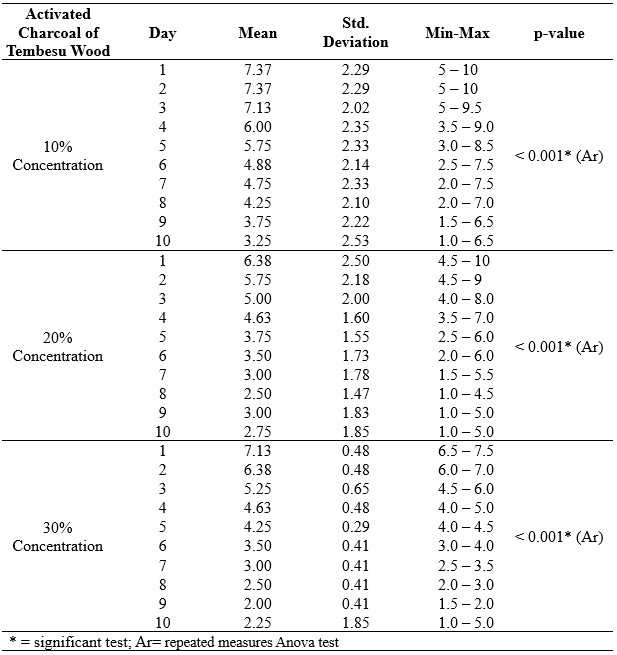

Two hundred and seventy-two patients met the eligibility criteria, however five refused to participate in the study, declining the proposal because they did not want to answer the questions on the questionnaire. Among the participating patients, two refused the music-based intervention after answering the first questions of the questionnaire; one due to clinical aggravation and the other due to the need for rest. The flowchart of the study is depicted in Figure 1. Patients were mostly Italian (94.4%), 59.6% were males. For 95.1% of the participants, the questionnaire had a good (66.8%) or complete intelligibility (28.3%). Only 4.9% believed that the questions were fairly comprehensible. Answers regarding the usual everyday life are described in Table 2 (Q1-Q8). Usually, patients listened to music to get a pleasant distraction (69.7%) or to relieve from negative feelings (22.5%) and what achieved from listening to music was relax (41.6%) or leisure (18.4%).

Table 2. Habitual listening to music

Preferences specific to the hospitalization

Most of patients at the time of hospitalization would have preferred listen to music (84.6%) rather than other activities such as reading, watching TV, etc. Accordingly, the patients declared they would like to listen to music during hospitalization (95.5%), granting that it would have a positive effect on them (96.6%), mainly through piped music (93.3%), and without any distinction in administration time (85.4%) (Table 3 Q9-Q15). The genre of music habitually listened highly correlated with the one desired during hospitalization (Cramer’s V = 0.928, p<0.0001), with only 6 patients preferring a genre of music different from the one usually preferred.

Table 3. Views on music listening during hospitalization.

Perceptions experienced after music-based intervention

Answers given after the music treatment are reported in comparison with answers given before the treatment (Table 4). Patients who appreciated listening to music increased from 93.6% of the everyday life, to 95.5% in their perception of hospitalization, and up to 98.5% after hospitalization (Q1, Q14 and Q16), although the latter percentage is slightly inflated by the fact that two patients who didn’t habitually like music refused the music treatment and therefore did not answer to the post treatment questions (Table 4). These differences reached the statistical significance when comparing “yes” vs “I do not know” across the three periods (the only two “no” answers were missing at the post treatment, Cochran’s Q= 13.0, df=2, p=0.0015). According to the high percentage of patients declaring that they liked music, the degree of usefulness attributed to music was very high both before and after hospitalization (median= 4 in both, on a score from 1 to 5) (Table 4). There were high and significant correlations between the two (Spearman’s rho=0.631, p<0.0001) and difference between the two periods did not reach the statistical significance (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test Z = -1.821, p=0.0687), although 23 patients gave a score below 4 before hospitalization (8.6%, two patients scored 1, one scored 2 and 20 scored 3), who reduced to only 9 patients giving a score of 3 (3.4%). The emotional effects usually conveyed by music were significantly different from those conveyed during hospitalization (Q8 vs Q17, p<0.0001), with happiness falling from 17.2% to 8.7% and excitement from 9.4% to 0, while amusement/entertainment raised from 18.4% to 41.1% (Table 4). Also, the reasons why the patients listened to music changed from the usual habits to the idea the patients had about hospitalization and to what they have actually perceived during the hospitalization (Q7 vs Q12 vs Q18, p<0.0001): pleasant distraction went from 69.7% to 55.8% to 38.7%, while relief went from 22.5% to 35.2% to 60.0% (Table 4). Only 80 patients chose the same reasons for the three periods, mostly (90.0%) desired music for pleasant distraction.

Table 4. Perceptions experienced after music-based intervention.

Not surprisingly, the music treatment was appreciated especially by the patients who preferred listening to music rather than other activities such as reading, watching TV, etc.: all the 266 patients that had declared they would have liked listening to music appreciated the treatment, while 4 patients out of 39 that would have rather preferred other entertainment activities were then not sure about the music treatment (p<0.0001). However, the patients who preferred other activities were mainly satisfied by the music treatment. Finally, there were some differences between males and females (Table 5). In particular, males tended to habitually listen to music more than females (96.2% vs 88.0%, p=0.0161) and through different playback sources (p<0.0001), in particular males preferred radio and females preferred television. Females usually tended to listen to music more to get a pleasant distraction, achieving relaxing sensations while males more to get relief from negative feelings (p<0.0001), achieving leisure (p<0.0001). Of note the answers specific to hospitalization showed, at opposite, that females were more expecting to get relief, while males were more expecting to get a pleasant distraction (p<0.0001), a trend confirmed at the post treatment evaluation (p<0.0001).

Females rated the utility of listening to music slightly less than males as for their hospitalization expectance (p=0.0330, Mann-Whitney test), but without any difference at the post treatment evaluation, when at opposite their appreciation was even higher than those by males, although not significantly different (Table 5).

Table 5. Gender Differences to questionnaire responses

DISCUSSION

This pilot study aimed to determine the impact of a pre-recorded music-based intervention on music perception in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. This study, in line with others [16], describes an almost total appreciation for music in everyday life. The COVID-19 patients included in this study liked music even more in the perspective of hospitalization, with a further increase in the overall liking after the music-based intervention. Particularly, this observation emerged in females with a 99.1% of appreciation and a reduction from 6.5% to 0.9% of undecided/negative answers after the treatment. This implies that the musical listening confirmed and exceeded the usual expectations towards music, particularly in females, who showed a slightly lower preference for music than males in their habitual life. This observation provides support for the importance of music presence during hospitalization and potential benefits in COVID-19 patients. This study also shows that habitual preferences are closely related to those in the in-patient setting and should therefore be considered in order to direct music-based interventions [10,12-14]. The preference for Italian pop music reflects the cultural and musical background of the participants, considering their Italian origins and the high average age. Regardless of the usual musical medium, and in line with other studies [22], participants preferred piped music in the in-patient setting, while only 0.7% and 4.9% of them liked live music or music via earphones, respectively. It is conceivable that piped music represents a socially accepted medium in the care setting and that live music may represent an unrealistic novelty, especially given the restrictions and isolation during hospitalization. However, it must also be considered that the use of medical devices such as masks or helmets for ventilation makes it difficult or impossible to set up a system of music diffusion via earphones. Likewise, there are further complications in the hygienic handling of diffusion devices/music instruments in a COVID-19 environment, which must ensure minimal contamination of surfaces by microorganisms [23]. These limitations might have mitigated, in fact, the clear preference for piped music. The habitual listening to music was shown to find its place in numerous daily life activities (during free time, sports, or work). Similarly, the patients were willing to enjoy music at any time during hospitalization, being the preferred entertainment activity in hospital compared to other proposals, such as reading, watching TV, or taking drugs to relax. This may suggest the possibility to extend music not only to the in-patient rooms but also to the corridors, to the rooms used for clinical care services, and to the common spaces. The experimental intervention impacted the perception of the effects attributed to music. Feelings of pleasure and enjoyment were experienced by more than double the participants compared to the usual condition. Not surprisingly given the patients’ situation, happiness and joy decrease from 17.2% to 8.7% and the exciting/energizing effect was not perceived by anyone post-intervention. Similarly, the reasons that motivated the patients to listen to music were significantly different between everyday life, the hospitalization perspective, and the post intervention. The usefulness of listening music to alleviate unpleasant feelings including anxiety, fear, loneliness, and low mood had a significant increase after the music intervention. Furthermore, the degree of usefulness experienced with the intervention was greater than that usually perceived, even if the very high level of appreciation already in everyday life did not allow us to detect a statistically significant increase. No participant experienced little or no benefit from the intervention. The pre-recorded music was specifically designed according to general patient preferences and frameworks for entertainment and mood improvement, considering the need for emotional support in disease. In the literature, for example, it has been widely demonstrated that musical rhythms between 60 and 80 bpm or the use of musical instruments that are tuned to A432(Hz) can assist physical and emotional relaxation with a decrease in sympathetic nervous system activity, thus decreasing adrenergic activity, neuromuscular arousal, cardiovascular and respiratory rhythms, tension, metabolic rate, gastric acidity, motility, and sweat gland activity [10]. In this study, in line with findings in the literature, the effects of music listening can be traced back to the rationale with which the music was selected [10]. In fact, music selected to promote distraction, relaxation, entertainment and emotional support predominantly elicited relaxation and pleasure, recognised to distract, and alleviate unpleasant feelings such as anxiety, fear and stress. To confirm this, sadness, melancholy, love, nostalgia, and pride were evoked to a limited extent by listening to music. These findings support the directionality of the music-based intervention according to specific frameworks. Scientific rigour in music selection, the involvement of music experts, and the use of reporting guidelines can determine specific listener-perceived effects and allow for adequate replicability of the intervention. These data are in line with other studies that suggest that music-based intervention induced greater satisfaction and compliance in the patient pathway [18]. Awareness and recognition of the usefulness of music by the patient can in fact mitigate the decision-making processes of care and self-care. Structural changes can improve the environment and even encourage interaction between operators and patients [24]. However, economic, and organizational aspects must be considered in order to integrate this kind of service. In this study, the design of a piped intervention based on pre-recorded music tracks, according to scientific frameworks, required limited costs for the music setting by a professional and the copyright licenses, given that the in-patient area already had ceiling-mounted audio diffusion media. Also considering that the use of the music playback devices avoided any risk of infection from contamination, the safety of the intervention, in addition to the cost-effectiveness, was evident. Other studies have already amply demonstrated the benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness in multiple contexts and with different music playing methods [25,26].

CONCLUSION

This pilot study explored in-patients’ preferences, utility that comes from music, usages, and expectation from the effect of music in COVID-19 patients, before and after music-based intervention, and was carried out in response to a lack of studies in the literature and methodological weaknesses of publications. In this study, music was the most welcome activity during the hospitalization. The experimental intervention, directed according to reference frameworks, significantly impacted on the utility, on the evoked emotions, and on the self-reported effects of music during hospitalization for COVID-19. This result provides support for the intervention with pre-recorded music as an integrated standard in treatment protocols to meet the need for social and emotional support in hospitalized patients for COVID-19 and possibly in similar settings of hospitalization in isolation.

Limitations

It was not possible to recruit patients younger than forty years of age. This made it impossible to evidence some generational differences between the participants. A similar consideration regards the lack of heterogeneous in nationality. In addition, participants could not enjoy parental visits during their hospital stay due to COVID-19 restrictions, limiting the comparison with the more general situation of parental social support. Other clinical variables such as anxiety levels, loneliness in the healthcare relationship [27,28], psycho-physical distress and respiratory complications, which could have impacted the perception of the music experienced, were not considered. In the literature, there is ample evidence that patients with high levels of anxiety and distress obtained greater benefit from music [1,3,6,18,29-32], so although the aim of this study was not to measure changes in health outcomes, a correlation between high levels of psycho-physical distress on admission and musical perceptions related to the need to alleviate unpleasant feelings is likely. Preferences, beliefs, and attitudes towards the different genre of music, also in the context of socio-demographic characteristics should lead future study. The catchiness, use of melody, rhythm, and ease to understand of lyrics should be explored as well. Future randomised controlled trials using the same framework should be considered, to determine its effects on healthcare outcomes in multiple populations with similar needs for social and emotional support. The appropriate use of music may also be aimed at improving recovery time and reducing the need for medication to treat COVID19-induced psycho-physical distress [1,33,34]. Hopefully future studies will consider patients’ perceptions as a crucial factor in determining the specific psychophysical effects of music. Based on this knowledge it will be possible to structure, implement and systematically replicate music in healthcare environment.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

Dr. Alessio Pesce: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Department of Internal Medicine, Local Health Authority ASL2, Savona (Italy), Piazza Sandro Pertini n. 10, 17100 Savona, Italy. Tel: +39 340 7114674. E-mail: alessio.pesce@uniupo.it; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2702-4101

Dr. Francesca Lantieri: Software, Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Department of Health Science, Biostatistics Unit, University of Genoa, Italy, via Pastore 1, 16132 Genova, Italy. E-mail: f.lantieri@unige.it; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8923-0165

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the staff of the Internal Medicine department at the dedicated Covid-19 hospital in Albenga, and Dr. Letizia Ceravolo for revising the English-language manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Chen X, Li H, Zheng X, Huang J. Effects of music therapy on COVID-19 patients’ anxiety, depression, and life quality: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Jul 2;100(26): e26419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026419.

- Bradt J, Dileo C, Myers-Coffman K, Biondo J. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Oct 12;10(10):CD006911. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006911.pub4.

- Kakar E, Billar RJ, van Rosmalen J, Klimek M, Takkenberg JJM, Jeekel J. Music intervention to relieve anxiety and pain in adults undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2021 Jan;8(1):e001474. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001474.

- Boster JB, Spitzley AM, Castle TW, Jewell AR, Corso CL, McCarthy JW. Music Improves Social and Participation Outcomes for Individuals With Communication Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Music Ther. 2021 Mar 16;58(1):12-42. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thaa015.

- Cheng J, Zhang H, Bao H, Hong H. Music-based interventions for pain relief in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Jan 15;100(2):e24102. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024102.

- Gauba A, Ramachandra MN, Saraogi M, Geraghty R, Hameed BMZ, Abumarzouk O, Somani BK. Music reduces patient-reported pain and anxiety and should be routinely offered during flexible cystoscopy: Outcomes of a systematic review. Arab J Urol. 2021 Mar 3;19(4):480-487. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2021.1894814.

- Kakar E, Venema E, Jeekel J, Klimek M, van der Jagt M. Music intervention for sleep quality in critically ill and surgical patients: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021 May 10;11(5):e042510. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042510.

- Chen X, Li H, Zheng X, Huang J. Effects of music therapy on COVID-19 patients’ anxiety, depression, and life quality: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Jul 2;100(26):e26419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026419.

- Sliwka A, Pilinski R, Przybyszowski M, Pieniazek M, Marciniak K, Wloch T, Sladek K, Bochenek G, Nowobilski R. The influence of asthma severity on patients’ music preferences: Hints for music therapists. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018 Nov;33:177-183. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.005.

- Williams C, Hine T. An investigation into the use of recorded music as a surgical intervention: A systematic, critical review of methodologies used in recent adult controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2018 Apr;37:110-126. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.02.002.

- Greenberg DM, Baron-Cohen S, Stillwell DJ, Kosinski M, Rentfrow PJ. Musical Preferences are Linked to Cognitive Styles. PLoS One. 2015 Jul 22;10(7):e0131151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131151.

- (1) Robb SL, Hanson-Abromeit D, May L, Hernandez-Ruiz E, Allison M, Beloat A, Daugherty S, Kurtz R, Ott A, Oyedele OO, Polasik S, Rager A, Rifkin J, Wolf E. Reporting quality of music intervention research in healthcare: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2018 Jun;38:24-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.02.008.

- (2) Robb SL, Burns DS, Carpenter JS. Reporting Guidelines for Music-based Interventions. Music Med. 2011 Oct;3(4):271-279. doi: 10.1177/1943862111420539.

- Carter JE, Pyati S, Kanach FA, Maxwell AMW, Belden CM, Shea CM, Van de Ven T, Thompson J, Hoenig H, Raghunathan K. Implementation of Perioperative Music Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Anesth Analg. 2018 Sep;127(3):623-631. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003565.

- Pesce A. Music before undergoing cardiac catheterisation between preference and reality. A pilot study. Prof Inferm. 2021 Oct-Dec;74(4):272. doi: 10.7429/pi.2021.744272a.

- Cabedo-Mas A, Arriaga-Sanz C, Moliner-Miravet L. Uses and Perceptions of Music in Times of COVID-19: A Spanish Population Survey. Front Psychol. 2021 Jan 12;11:606180. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606180.

- Alter DA, O’Sullivan M, Oh PI, Redelmeier DA, Marzolini S, Liu R, Forhan M, Silver M, Goodman JM, Bartel LR. Synchronized personalized music audio-playlists to improve adherence to physical activity among patients participating in a structured exercise program: a proof-of-principle feasibility study. Sports Med Open. 2015;1(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40798-015-0017-9.

- Jayakar JP, Alter DA. Music for anxiety reduction in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017 Aug;28:122-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.05.011.

- Bradt J, Dileo C. Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):CD006902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006902.

- Makama JG, Ameh EA, Eguma SA. Music in the operating theatre: opinions of staff and patients of a Nigerian teaching hospital. Afr Health Sci. 2010 Dec;10(4):386-9.

- Graff V, Wingfield P, Adams D, Rabinowitz T. An Investigation of Patient Preferences for Music Played Before Electroconvulsive Therapy. J ECT. 2016 Sep;32(3):192-6. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000315.

- Lee KC, Chao YH, Yiin JJ, Chiang PY, Chao YF. Effectiveness of different music-playing devices for reducing preoperative anxiety: a clinical control study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011 Oct;48(10):1180-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.04.001.

- Folsom S, Christie AJ, Cohen L, Lopez G. Implementing Telehealth Music Therapy Services in an Integrative Oncology Setting: A Case Series. Integr Cancer Ther. 2021 Jan-Dec;20:15347354211053647. doi: 10.1177/15347354211053647.

- Drahota A, Ward D, Mackenzie H, Stores R, Higgins B, Gal D, Dean TP. Sensory environment on health-related outcomes of hospital patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;2012(3):CD005315. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005315.

- Chlan LL, Heiderscheit A, Skaar DJ, Neidecker MV. Economic Evaluation of a Patient-Directed Music Intervention for ICU Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilatory Support. Crit Care Med. 2018 Sep;46(9):1430-1435. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003199.

- DeLoach Walworth D. Procedural-support music therapy in the healthcare setting: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005 Aug;20(4):276-84. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.02.016.

- Pesce, A. Solitudine nella relazione di cura: un concetto dimenticato tra i fondamenti di cura. L’infermiere, (2020) 1–7

- Karhe L, Kaunonen M, Koivisto AM. Loneliness in Professional Caring Relationships, Health, and Recovery. Clin Nurs Res. 2018 Feb;27(2):213-234. doi: 10.1177/1054773816676580.

- Bradt J, Dileo C, Shim M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 6;2013(6):CD006908. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006908.

- Kühlmann AYR, de Rooij A, Kroese LF, van Dijk M, Hunink MGM, Jeekel J. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br J Surg. 2018 Jun;105(7):773-783. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10853.

- Walter S, Gruss S, Neidlinger J, Stross I, Hann A, Wagner M, Seufferlein T, Walter B. Evaluation of an Objective Measurement Tool for Stress Level Reduction by Individually Chosen Music During Colonoscopy-Results From the Study “ColoRelaxTone”. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020 Sep 15;7:525. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00525.

- Monsalve-Duarte S, Betancourt-Zapata W, Suarez-Cañon N, Maya R, Salgado-Vasco A, Prieto-Garces S, Marín-Sánchez J, Gómez-Ortega V, Valderrama M, Ettenberger M. Music therapy and music medicine interventions with adult burn patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns. 2022 May;48(3):510-521. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2021.11.002.

- Raglio A. Therapeutic Use of Music in Hospitals: A Possible Intervention Model. Am J Med Qual. 2019 Nov/Dec;34(6):618-620. doi: 10.1177/1062860619850318.

- Biondi Situmorang DD. Music Therapy for the Treatment of Patients With COVID-19: Psychopathological Problems Intervention and Well-Being Improvement. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2021 May;29(3):e198. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000999.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

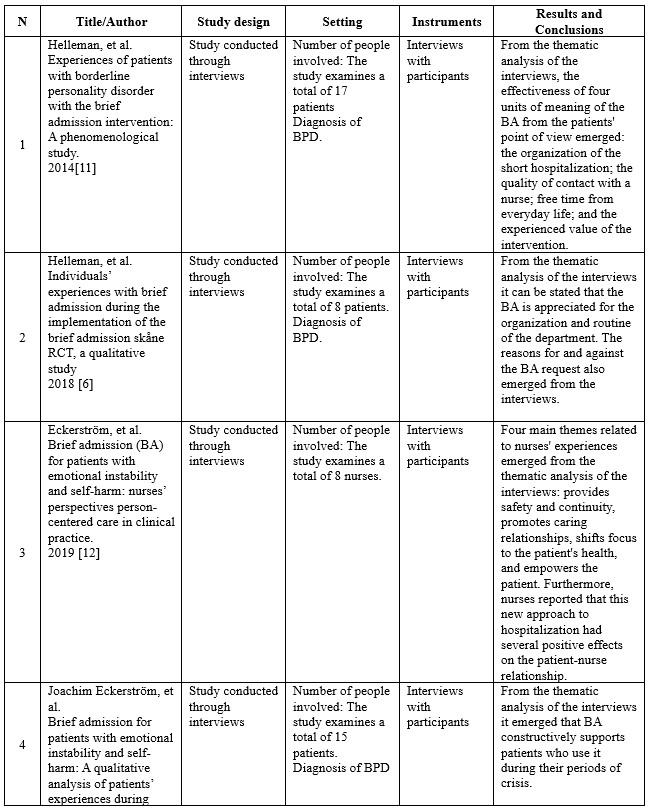

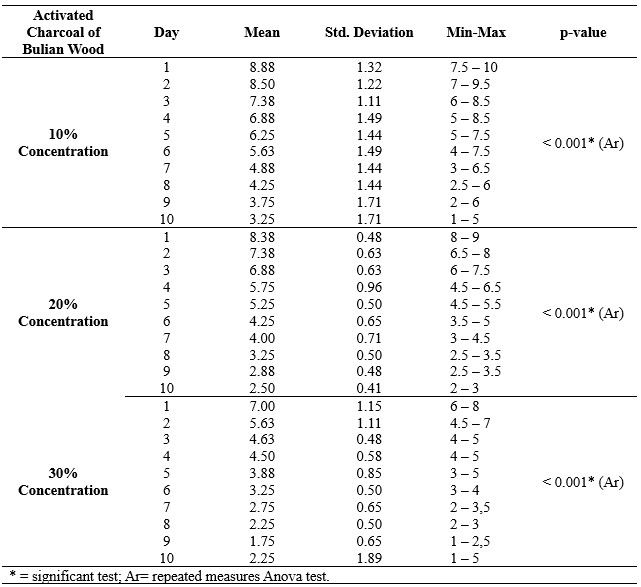

Effectiveness of nursing intervention in short-term hospitalization for patients suffered from borderline personality disorder and self-harm. A narrative literature review

Antonino Calabrò1, Federica Ilari2, Lorenzo Rizzo3, Alessia Lezzi4, Simone Zacchino4, Pierluigi

Lezzi5, Giovanni Maria Scupola6, Marta Fanton7, Roberto Lupo6, Elsa Vitale8*

- Psychiatry Unit, Nuovo Ospedale Degli Infermi, Biella, Italia

- Department of Translational Medicine, University of Eastern Piedmont, Biella, Italy

- Eating Disorders Cente, Villa Eèa Cooperative Città Azzurra, Bolzano, Italy

- Associazione Nazionale Italiana Tumori, Lecce, Italy

- Neurology Unit, Vito Fazzi Hospital, Local Health Authority (ASL) Lecce, Italy

- Department of Emergency Medicine, San Giuseppe da Copertino Hospital, Local Health Authority Lecce, Italy

- Azienda ospedaliera nazionale SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo, S.C. Cardiologia, Alessandria, Italy

- Department of Mental Health, Local Health Authority (ASL) Bari, Italy

*Corresponding Author: Elsa Vitale, Department of Mental Health, Local Health Authority (ASL) Bari, Italy. E-mail: vitaleelsa@libero.it; ORCID: 0000-0002-9738-3479.

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Personality disorder sufferers with severe self-harm and experience long psychiatric hospitalizations have complex mental health conditions and are at risk of suicide. When the symptoms of emotional instability are combined with self-harm, the resulting crisis often becomes difficult for patients and caregivers to manage. To improve care during these crises, the Dutch Multidisciplinary Guideline for Personality Disorders designates “brief admission” (BA) hospitalizations as an ameliorative intervention.

Objective: To describe the effectiveness of short hospitalization nursing care for people with borderline personality disorder and who practice self-harm, compared to ordinary hospitalization.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted through the Embase and CINAHL databases, the selected articles had to answer the following research questions: “what are the observable benefits of short-term hospitalization on patients with borderline personality disorder?”; and “what are the benefits compared to short hospitalization operators?”.

Results: Seven studies were selected. The results show that BA was perceived as an effective nursing intervention, which promoted the patient’s self-determination and self-care. This helped increase confidence in daily life and allowed people to maintain their daily routines, work, and relationships by decreasing long hospitalizations and increasing patient compliance. There has also been benefit from the staff, who report an improvement in work quality.

Conclusions: This type of hospitalization has developed in Northern European states. BA has never been tested in the Italian healthcare sector. It would be appropriate and desirable, given the results obtained, to experiment with this procedure also in Italy to obtain specific feedback regarding the relationship of short-term hospitalization with our National Health Service. It is hoped that this research can be a stimulus in this sense.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Nursing Management, Brief Admission, Patient Experiences, Self-Harm, Short-term hospitalization.

INTRODUCTION

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is the most common personality disorder observed in clinical settings and within societies around the world. This disorder is characterized by various elements: a set of unstable and changing interpersonal relationships; emotional instability which often manifests itself with sudden attacks of anger; poor impulse control associated with self-harm; identity disorders [1]. The prevalence of people with borderline personality disorder in general and clinical psychiatric populations is approximately 4% and 20%, respectively. Approximately 75% of patients with borderline personality disorder attempt suicide and 10% succeed in their attempt [2]. Self-harm is part of the signs and symptoms of BPD and is the act of harming oneself voluntarily but without a conscious or declared suicidal intention (non-suicidal self-harm ANS) [3].

It is a very common phenomenon widespread especially among young people, in fact, it is also a major health care problem among both outpatient psychiatric patients and those in hospital care, with incidence rates of 55% and 65%, respectively. When the subject with BPD practices recurrent acts of self-harm, it is due to his inability to express his own internal suffering, he attacks his own body because he has the impression that by doing so, he will calm down. This becomes difficult to manage both for the patients themselves but above all for the healthcare personnel who deal with them [2]. Patients with borderline personality disorder are followed in both outpatient and hospital settings. Treatment typically begins with community services with day care and individual and/or group psychotherapy, depending on the individual [4].

When the behavior of these individuals becomes dangerous to their health, treatment may sometimes be necessary. interruption of outpatient treatment, preferring hospitalization in a psychiatric ward to ensure good protection for the patient. However, unplanned or long-term hospitalization for these patients without a clear treatment structure is very often associated with clinical and functional decompensation [5]. Hospitalization has been shown to have limited value, with often a failure to eradicate ideas. aimed at anti-conservative actions, with the development of possible negative side effects such as the beginning of a period of regression and the continuous need for repeated hospitalizations over time [6].