COVID-19 Vaccines Side Effects Among Iraqi people In Kurdistan Region: A cross-sectional study

Rebar Yahya Abdullah1*, Arazoo Issa Tahir2, Dlkhosh Shamal Ramadhan3, Zuhair Rushdi Mustafa4, Kawther Mohammed Galary5

1 MSc. (Maternity and Community Health Nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Duhok,Kurdistan,Iraq).

2 MSc (Nursing Department, Bardarash Technical Institute, Duhok Polytechnic University, Kurdistan,Iraq).

3 MSc (Maternity and Community health nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq)

4PhD (Adult Nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq).

5 MSc (Maternity and Community Health Nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq).

*Corresponding Author: Rebar Yahya Abdullah, Maternity and Community Health Nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq.

E-mail: rebar.abdullah@uod.ac

Cita questo articolo

ABSTRACT

Background: Communities around the world have expressed concern about the safety and side effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. The adverse effects of the Covid-19 vaccines played a critical role in public trust in the vaccines. The current study aimed to provide evidence on the side effects of the BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech®); ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AstraZeneca®); BBIBP-CorVvaccine (Sinopharm®) COVID-19 vaccines.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study design was performed from April 26th, 2021, to June 3rd, 2021. Convenience sampling was used to select respondents; face validity was performed to the mandatory multiple-choice items questionnaire to cover the respondent’s demographic characteristics, coronavirus-19 related anamneses, and the side effect duration of coronavirus-19 vaccines, the data were analyzed by using descriptive statistics.

Results: The 588 participants enrolled in the current study. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine received 49.7%, followed by BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and BBIBP-CorV (39.5% and 10.9%). The most common complaint was headache (61.2%), followed by vaccine injection site discomfort (58.8%), fatigue (49.7%), fever (48.3%), muscle discomfort (42.9%), and approximately (10.5% and 10.2%) had injection site swelling and nausea, respectively. Most of those surveyed had post-vaccine symptoms for one to two days (25.2%), (41%), and only a small percentage (3.7%) experienced them for over one month. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine handled 53% of the side effects, followed by BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (42%) and BBIBP-CorV vaccines (5%).

Conclusion: Prevalence of various local and systemic vaccines side effects, such as headache, fever, and pain at the injection site, was observed. Almost all participants had mild symptoms and were well-tolerated .AstraZeneca® vaccine has the most side effects, followed by the Pfizer® vaccine, and the Sinopharm® vaccine has the least. More independent studies on vaccination safety and public awareness are critical to improving public trust in vaccines.

Keywords: COVID-19; Vaccines; Side effects; Prevalence; Cross-sectional design.

INTRODUCTION

Millions of people around the world were infected by the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) within three months, until World Health Organization declared it as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a coronavirus that belongs to the Coronaviridae family's Sarbecovirus subgenus, and a non-segmented positive-sense Ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus encompasses it [2]. Older individuals are at an increased risk of being infected with the SARS-CoV-2 [3]. Most vaccine options target the spike (S) protein. It is the principal target of neutralizing antibodies. It helps to neutralize antibodies to prevent the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor binding motif (RBM) from engaging with the host cell [4, 5]. The vaccine development for COVID-19 prevention has grown into a struggle between viruses and humans, which has made it more complicated, along with the discovery of other related strains. Many platforms are attempting to grow, with Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and RNA-based platform showing the most promise [6]. Several countries have entered the vaccine development battle, hastening the clinical trial phase and attempting to produce an efficient and safe vaccine against COVID-19 [7]. The COVID-19 vaccines have been studied in large, randomized-controlled studies with people of all ages, genders, nationalities, and individuals with known medical disorders. Across all demographics, the vaccines have shown a high level of effectiveness and are safe and efficacious in patients with various underlying diseases [8]. According to a recent national study [9], the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine were the most common reason for vaccine hesitancy among the population in the United Kingdom (U.K.). This finding was confirmed in the context of COVID-19 vaccinations, as fear of side effects has been cited as the primary reason for healthcare workers and students in Poland refusing to accept the Covid-19 vaccine [10, 11]. Vaccines are not completely free of side effects or complications [26], headache, nausea, pain, redness, and swelling are early adverse effects of vaccines that must be expected when taking vaccines [27]. Furthermore, conditions like blood clotting were suggested to be caused by the administration of COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca. [28,29].The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine among vaccinated people in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study was conducted using a cross-sectional design from April 26th to June 3rd, 2021, in the Kurdistan region, Iraq.

Samples and sampling

An Internet-based study in the Kurdistan region of Iraq recruited to enroll a sample size of 588 people from people who had been vaccinated with one of the following vaccines: BBIBP-CorV, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, and BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. However, illiterate and old age individuals were interviewed directly by authors to increase the sample representation. The individuals were invited by using invitation links in Viber™, Facebook™, and WhatsApp™ groups by using a non-random convenience sampling method. A Google™ form document was utilized to host and deliver the questions to responders. The inclusion criteria were participants who received one of the three mentioned COVID-19 vaccines and either received the first or second dose of the vaccine.

Instruments of the study

The self-administered questionnaire of the present study, composed of nine mandatory multiple-choice items, has been adapted from previous studies and World Health Organization data [12, 13]. The questionnaire was divided into four parts: the first part included demographic data, including gender, age, and profession; the second part dealt with COVID-19 history, including COVID-19 previous infection, type and dose of COVID-9 vaccines, and medical history like having any chronic disease; the third part included the side effects and side effect duration of COVID-19 vaccines.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics were performed to determine the study variables; age, gender, occupation, and the data that related to the COVID-19 vaccine. The current study used SPSS version 23 for the descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

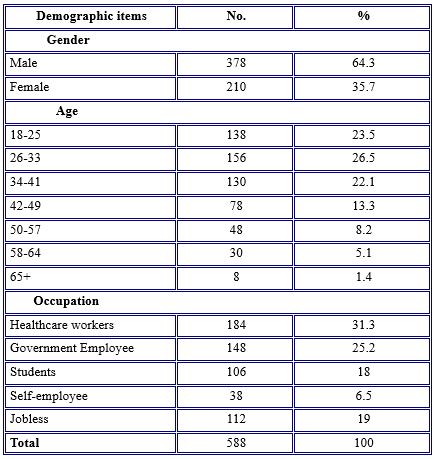

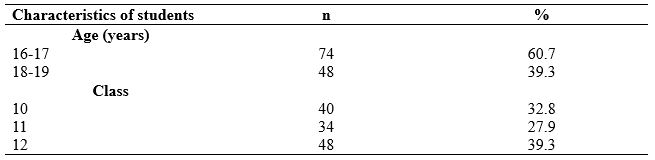

588 participants in the study. Nearly two-thirds of participants were males (64.3%); their mean age was 41.5 years and ranged between 18 and 65 years. Most of the participants were healthcare workers (31.3%), government employees (25.2%), jobless (19), students (18), and self-employed (6.5%), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of study participants

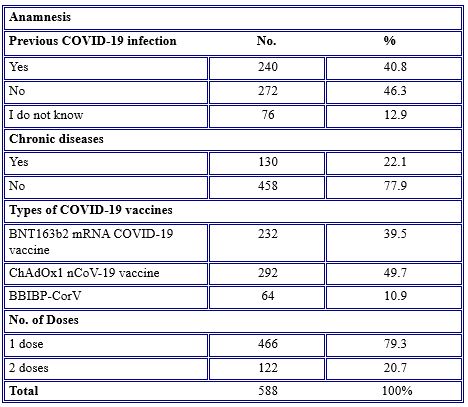

According to some questions stated in Table 2, nearly half (46.3%) of the participants did not infect before taking the vaccine. About (40.8%) reported that they were infected with COVID-19 previously. Compared with a tiny percentage (12.9%) having the vaccine without knowing whether they were infected with the COVID-19 virus or not.

Table 2. COVID-19 vaccines related anamnesis

Regarding chronic diseases among the participants who had the COVID-19 vaccine, over three-quarters (77.9%) had no chronic diseases. The most common types of vaccines received by the participants were ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (49.7%), followed by BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and BBIBP-CorV (39.5% and 10.9%). Regarding the number of vaccine doses gained, over three-quarters (79.3%) of participants had a single dose of vaccine at the time of the study.

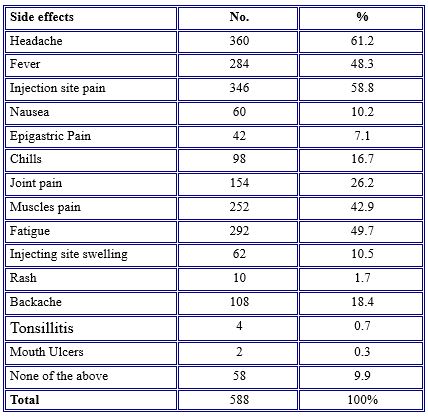

Regarding the response of the participants toward COVID-19 side effects, they reported having at least one side effect after the COVID-19 vaccine job. The most common side effects among the study population (61.2%) were headaches, followed by vaccine injection site pain (58.8%), fatigue (49.7%), fever (48.3%), muscle pain (42.9%), and nearly the same percentage (10.5% and 10.2%) complained of injection site swelling and nausea, respectively. Rarely (0.3% and 0.7%) reported mouth ulcers and tonsillitis, side effects of the vaccine, as noted in Table 3.

Table 3. Prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine side effects among study participants

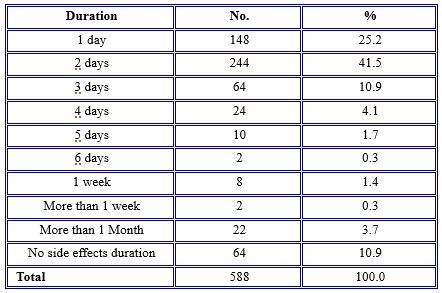

Table 4 shows that, for the duration of the occurrence of side effects, the vast majority (41.5%) of the participants had post-vaccination side effects for about two days, while 25.2% had them for one day, and 10.9% of the individuals complained about side effects for three days. 3.7% of them had a longer duration of side effects for over one month.

Table 4. The duration of side effects of COVID-19 vaccines

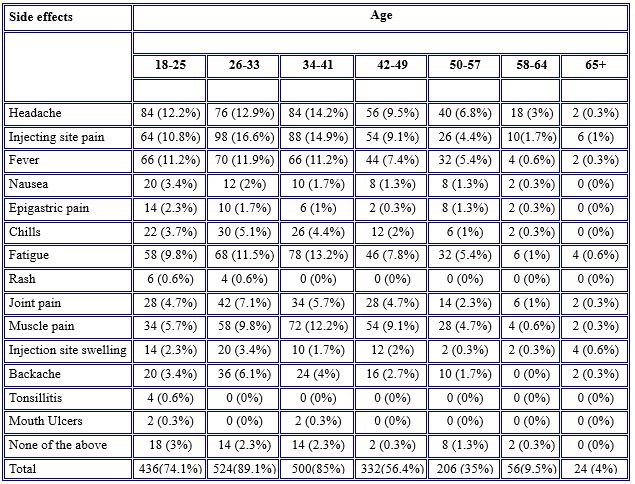

Regarding side effect prevalence with different age groups, symptoms were more common among the younger age groups ranging from 18 to 57 years old. Symptoms were much less severe in older age groups (58–64), with no noticeable side effects observed in participants older than 60 years old. Headache was more common in the age group 34-41 years old (14.2%); injection site pain was more common in the age group 26-33 years old (16.6%); fatigue was more common in the age group 34-41 years old (13.2%) as in Table 5.

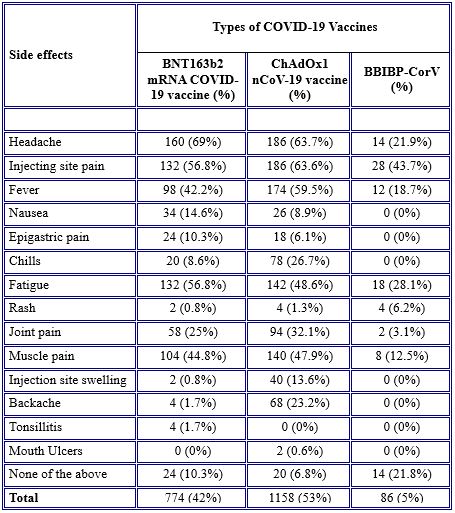

Concerning the occurrence of side effects among BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, and BBIBP-CorV vaccines, the vast majority (53%) of the side effects were because of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, followed by BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (42%), BBIBP-CorV vaccines (5%) were safer than BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine vaccines in that almost all side effects occurred among vaccinated individuals.

Table 5. Prevalence of the side effects of COVID-19 vaccines among age groups

Some side effects such as nausea, epigastric pain, chills, injection site swelling, backaches, tonsillitis, and mouth ulcers have not occurred at all. Only a few participants (43.7%, 28.1%, 21.9%, and 18.7%, respectively) experienced injection site pain, fatigue, headache, and fever after receiving the BBIBP-CorV vaccine.

Most of the symptoms were observable in those who received the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine and BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine vaccines, although symptoms were more common in individuals vaccinated with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. Common side effects between BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine were headache (69 % versus 63.7 %), injection site pain (56.8 % versus 63.6 %), fever (42.2 % versus 59.5 %), fatigue (56.8 % versus 48.6%), and muscle pain (44.8 versus 47.9 %) as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Occurrence of side effects between vaccines

DISCUSSION

During the pandemic of COVID-19, the World Health Organization recommended that all nations strive to maintain population immunization. Although legislation and policies in this region are different, they still emphasize people at risk of coronavirus disease, such as healthcare workers, the elderly, and patients with chronic conditions [14]. Thus, the results of the current study showed that most of the participants (31.3%) were healthcare workers (males 64.3%), and most of them (46.3%) did not affect COVID-19. A similar study was conducted in India, which stated that, according to government regulations, the vaccine was initially administered to healthcare personnel in both government and private hospitals throughout India [15]. Correspondingly, in the US, priority is given mainly to all healthcare workers, then individuals who have an underlying condition, and after that to all essential service workers and older adults [16].

Because of the speed of COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing, concerns among the public have emerged about the safety of these new vaccines. No serious safety problems were reported [17]. Overall, COVID-19 vaccines are safe and will protect the community from developing severe COVID-19 disease and dying from COVID-19. BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is an mRNA-based vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine is an Adenovirus vaccine, and BBIBP-CorV is a vaccine [18]. According to the research, COVID-19 vaccination adverse effects are characterized as either local or systemic reactions, with severity ranging from mild to moderate [19]. The mRNA-based vaccines such as BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine have the highest level of side effects reported, except for diarrhea and arthralgia [20]. Since some of the vaccinated individuals in the current study received the mRNA-based vaccines, they were not free from side effects. No serious events associated with the COVID-19 vaccines, such as vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia reported. However, most of the side effects were common and non-life-threatening. The side effects were systematic and local. The systemic reactions were headache (61.2%), fatigue (49.7%), fever (48.3%), muscle pain (42.9%), joint pain (26.2%), backache (18.4%), chills (16.7%), nausea (10.2%), epigastric pain (7.1%), and rash (1.7%), whereas the local reactions were injection site pain and injection site swelling (50.8%) and (10.5%), respectively. The rarest side effects were tonsillitis (0.7%) and mouth ulcers (0.3%). These findings are in line with those reported in the literature and reported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which are: injection site pain, fatigue, headache, fever, chills, muscle pain, and joint pain are common side effects of COVID-19 vaccines [21, 15]. Similar findings were observed in the Czech Republic where the most common side effects among vaccinated individuals were injection site pain, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, and feeling unwell [12]. Also, a retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted among Saudi residents to study the side effects of the BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. The study found that the most common symptoms were injection site pain, fever, headaches, flu-like symptoms, and tiredness. Less common side effects were tachycardia, generalized body aches, shortness of breath, joint pain, chills, and drowsiness. Rare side effects were tenderness, lymph node swelling, and Bell’s palsy [22]. In contrast to our study, in a systematic review study, the most common side effects were arthralgia (20). Mild to moderate side effects are experienced by vaccinated individuals. They are signs that the immune system of the body is responding to the vaccine and building protection against the COVID-19 virus (23/24). Also, in the present study, we found that the duration of post-vaccination side effects varied among participants. The majority (41.5%) were complaining about the side effects for two days, whereas 25.2% had side effects for one day, and 10% for three days. Only 3.7% had long-duration side effects for over one month. These findings follow the current studies which state that most of the side effects occur within the next 3 days after vaccination [15]. Also, similar findings were reported by Riad et al., [12]. They found that the duration of general side effects following the vaccine was mainly one day (45.1%) or three days (35.8%), and only 1.4% of them had lasted over a month.

Also, it is important to highlight that the prevalence of side effects was higher among younger individuals (> 49 years old) and almost no noticeable side effects occurred among older participants (60 years old). These findings are consistent with those published by the FDA, which found that injection site pain, weariness, headache, and muscle soreness were more common in the 55-year-old group than in the > 55-year-old group [21, 15]. Also, the same findings reported among the Czech Republic and Saudi residents, respectively [12], reported that younger adults 43 years old were more frequently affected by side effects, and [22] concluded that the frequency of side effects was higher in individuals younger than 60 years of age, except for injection site pain, which was more frequent among those 60 years old.

Concerning the comparison of the occurrence of side effects between BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, and BBIBP-CorV vaccines, the findings of the present study revealed that there were substantial variations between these vaccines in the presence of side effects. The majority (53%) of side effects were because of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, followed by BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (42%) except for headache, nausea, epigastric pain, fatigue, and tonsillitis which were more sever in BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine than ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine. The current study found BBIBP-CorV vaccine was safer than BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine vaccines in all side effects that occurred among vaccinated individuals. This finding is supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials (RCTs), which revealed that those who received mRNA-based vaccines had higher rates of side effects in reactogenicity [20]. The same findings were documented in Jordan. 2213 individuals received BBIBP-CorV, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, and other vaccines. They found that those who received the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine reported the most abundant post-vaccination symptoms, while most of those who received the BBIBP-CorV vaccine were free from symptoms [23]. Another study was conducted to assess the symptoms following the COVID-19 vaccine among residents in India. 5396 people responded to the survey. The findings revealed that the frequency of experiencing symptoms following the BBIBP-CorV vaccine was less (24.4%) compared to BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine 70.7% [25]. As seen, the BBIBP-CorV vaccine has few side effects compared to other vaccines.

CONCLUSIONS

The most common side effect of the BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, and BBIBP-CorV among the vaccinated population of the current study was headaches, injection site pain, injecting site swelling, fatigue, fever, muscle pain, joint pain, backache, chills, nausea, epigastric pain, and rash. These side effects were consistent with the data reported in the literature. Most of these side effects were mild, and no serious incidents were documented. Symptoms were more common in younger people. Although data reported in the literature showed that mRNA-based vaccines such as BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine had higher side effects, However, the current study found that the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, which is an adenovirus-based vaccine, had more side effects than other vaccines, and the BBIBP-CorV vaccine had the lowest side effects compared to the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine and BNT163b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine vaccines.

Limitations

The limitation of the current study is that it was difficult to measure the severity of the side effects because the study is a survey-based technique. Thus some side effects needed to be measured by using instruments or tools, for instance, measuring body temperature by the thermometer to know the severity of fever, and using a pain scale to measure headache, joint pain, and muscle pain. Also it is prone to selective bias as it is internet based study, not everyone has equal chance to be included in the study. Further studies needs to be done with more representative samples concerning COVID-19 intention.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

The current study was not funded by any financial resources.

Ethics

The present study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration”. Study approval was obtained by written authorization of the Ethics Committee of the College of Nursing at Duhok University. The approval is without a serial number and verbal informed consent has been obtained from each participant before participation in the current study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to all respondents who took part in this online survey. We highly appreciated their time and effort.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT - https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf. .

- Zhuo Zhou , Lili Ren , Li Zhang , Jiaxin Zhong , Yan Xiao , Zhilong Jia et alHeightened innate immune responses in the respiratory tract of COVID-19 patients. Cell Host Microbe .2020; 27, 883-890.e2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 information page (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019 -ncov/index.html).

- Addetia A, Crawford KHD, Dingens A, Zhu H, Roychoudhury P, Huang ML, Jerome KR, Bloom JD, Greninger AL. Neutralizing Antibodies Correlate with Protection from SARS-CoV-2 in Humans during a Fishery Vessel Outbreak with a High Attack Rate. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Oct 21;58(11):e02107-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02107-20. PMID: 32826322; PMCID: PMC7587101.

- Thompson, C. P., Grayson, N. E., Paton, R. S., Bolton, J. S., Lourenço, J., Penman, B. S., Lee, L. N., Odon, V., Mongkolsapaya, J., Chinnakannan, S., Dejnirattisai, W., Edmans, M., Fyfe, A., Imlach, C., Kooblall, K., Lim, N., Liu, C., López-Camacho, C., McInally, C., ... Girvan, M.. Detection of neutralising antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 to determine population exposure in Scottish blood donors between March and May 2020. Eurosurveillance, 25(42). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.42.2000685

- Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. New England Journal of Medicine..2020; 21;382(21):1969-73.

- Caddy S. Developing a vaccine for covid-19. BMJ 2020;369:m1790 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1790

- World Health Organization. . Safety of covid-19 vaccines. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/safety-of-covid-19-vaccines.2020.

- Luyten, J.; Bruyneel, L.; van Hoek, A.J. Assessing vaccine hesitancy in the UK population using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. 2019;37, 2494–2501. [CrossRef] [PubMed] .

- Szmyd, B.; Bartoszek, A.; Karuga, F.F.; Staniecka, K.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors. 2021; 9, 128. [CrossRef].

- Szmyd, B.; Karuga, F.F.; Bartoszek, A.; Staniecka, K.; Siwecka, N.; Bartoszek, A.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Attitude and Behaviors towards SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study from Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030218

- Riad, A.; Pokorná, A.; Attia, S.; Klugarová, J.; Košˇcík, M.; Klugar, M.Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Side Effects among HealthcareWorkers in the Czech Republic. Clin. Med., 10, 1428. https://doi.org/ .2021;10.3390/jcm10071428.

- World Health Organization. . Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/side-effects-of-covid-19-vaccines.2021

- World Health Organization. Guidance on routine immunization services during COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO European region: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.2020.

- Das, L., Meghana, A., Paul, P., & Ghosh, S. Are We Ready For Covid–19 Vaccines?–A General Side Effects Overview. Journal of Current Medical Research and Opinion.2021; 4(02).

- Barnabas, R. V., & Wald, A. A public health COVID-19 vaccination strategy to maximize the health gains for every single vaccine dose: American College of Physicians.2021.

- Gee, J. First month of COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring—United States, December 14, 2020–January 13, 2021. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021; 70.

- Wise, J. Covid-19: European countries suspend use of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine after reports of blood clots: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.2021.

- Oliver, S.E.; Gargano, J.W.; Marin, M.; Wallace, M.; Curran, K.G.; Chamberland, M.; McClung, N.; Campos-Outcalt, D.; Morgan, R.L.; Mbaeyi, S. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine-United States, December 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.2021, 5152, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormohammad A, Zarei M, Ghorbani S, Mohammadi M, Razizadeh MH, Turner DL, Turner RJ. Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. 2021; 9(5):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9050467.

- Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention. Local Reactions, Systemic Reactions, Adverse Events, and Serious Adverse Events: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Retrieved 5 June, from https://cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html.2021.

- El-Shitany, N. A., Harakeh, S., Badr-Eldin, S. M., Bagher, A. M., Eid, B., Almukadi, H., Sindi, N. Minor to Moderate Side Effects of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Among Saudi Residents: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. International journal of general medicine.2021;14, 1389.

- Hatmal MM, Al-Hatamleh MAI, Olaimat AN, Hatmal M, Alhaj-Qasem DM, Olaimat TM, Mohamud R. Side Effects and Perceptions Following COVID-19 Vaccination in Jordan: A Randomized, Cross-Sectional Study Implementing Machine Learning for Predicting Severity of Side Effects. 2021; 9(6):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060556

- World Health Organization. Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines. Retrieved 4 June, 2021, from https://who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/side-effects-of-covid-19-vaccines.2021

- Jayadevan, R., Shenoy, R. S., & Anithadevi, T. Survey of symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination in India. medRxiv.2021.

- Kimmel SR. Vaccine adverse events: separating myth from reality. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2113–20.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Reactions and adverse events of the pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine | CDC [Internet]. Centers Dis Control Prev. 2020 [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfi zer/reactogenicity.html

- Lee E, Cines DB, Gernsheimer T, Kessler C, Michel M, Tarantino MD, Semple JW, Arnold DM, Godeau B, Lambert MP, et al. Thrombocytopenia following Pfizer and moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Am J Hematol. [Internet]. 2021 [accessed. 2021 Aug 31];96:534–37. /pmc/articles/PMC8014568/ .

- European Medicines Agency. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine: EMA finds possible link to very rare cases of unusual blood clots with low blood platelets [Internet]; 2020 [accessed 2021 May 30].

The questionnaire

(COVID-19 Vaccines Side Effects Among Iraqi people In Kurdistan Region)

Dears the aim of this survey is to determine the (Prevalence of Covid-19 Vaccines side effects). We are grateful for filling in this survey from you and your family who got vaccinated. I would like to assure you that your answers will remain confidential and your personal details are not required. Also, your answers will be on online systems only.

- Age

18_25

26_33

34_41

42_49

50_57

57_64

65 and more

- Gender

Male

Female

- Occupation

Health care workers

Employee Government

Student

Own Job

Jobless

- Do you have any chronic disease?

Yes

No

- Did you infected with Covid-19 before?

Yes

No

I don't know

- Which Covid-19 Vaccine you took it?

Sinopharm

Astrazenea

Pfizer

- How many Doses you got it?

1 dose

2 doses

- Select the vaccine side effects that occurred with you

Headache

Vaccine injection site pain

Fever

Nausea

Epigastric pain

Chills

Joint pain

Muscles pain

Fatigue

Injection site swelling

Allergy

Backache

Tonalities

Mouth Ulcers

No one

- Duration of side effects of Covid-19 Vaccines

1 day

2 days

3 days

4 days

5 days

6 days

1 week

More than 1 week

More than 1 month

No duration

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Analysis of Determinants of Factors Related to the Performance of Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post Cadres in Kendari City: Cross Sectional Study

Saida, Rahmawati*, Wa Ode Syahrani Hajri

Department of Nursing, Medical of Faculty, Halu Oleo of University, Kendari, Indonesia

* Corresponding author: Rahmawati, Kampus Hijau Bumi Tridharma, Anduonohu, Kec. Kambu, Kota Kendari, Sulawesi Tenggara 93232, Indonesia, Orcid : https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6826-5393. Email: saida@uho.ac.id

Cita questo articolo

Abstract

Introduction: Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are diseases that are not caused by bacterial infection and are the main cause of death in the world. The increase in NCDs cases also occurred in Southeast Sulawesi Province (Indonesia), including Kendari City. The purpose of this study was to analyze the determinants of proxies related to the performance of Integrated Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post (INCDDP) cadres in Kendari City, Indonesia.

Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study carried out in Kendari City, Southeast Sulawesi Province (Indonesia), with a population of all INCDDP cadres in the working area of PHC Abeli, Lepo-Lepo, and Perumnas. The sample consisted of 56 responders. Data were analyzed univariate and bivariate statistics, using the chi-square test. Multivariate using logistic regression.

Results: The results of the research on the performance of INCDDP cadres were awards (p = 0.079), cadre training history (p = 0.031), infrastructure (p = 1.0) and knowledge (p = 0.007). The factor most related to the performance of INCDDP cadres was cadre knowledge (p = 0.019) with the coefficient of determination (R2) = 27.4%.

Conclusion: Cadre performance is related to awards, cadre training history, infrastructure and cadre knowledge. The most related factor to INCDDP cadre performance is cadre knowledge.

Keywords: Health-Cadres, Non-Commnicable Diseases, Performance, Health Services

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have become an enormous public health problem, especially in Indonesia [1]. It is marked by a shift in disease patterns which is often referred to as an epidemiological transition characterized by increased mortality and morbidity due to NCDs such as stroke, heart disease and diabetes mellitus [2].

NCDs account for 41 million deaths each year, equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally [3]. The 2018 Basic Health Research (BHR) results show an increase in the prevalence of NCDs compared to the 2013 BHR results [4]. NCDs cases in Southeast Sulawesi in 2018 were still relatively high [4,5]. In 2019, the number of hypertension sufferers in Kendari city was 13,807 cases, and DM patients were 2876 cases [6].

The high number of NCDs cases in Kendari City requires severe treatment by increasing the Public Health Center (PHC) role through the Integrated Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post (INCDDP), significantly expanding the part of cadres in the context of preventing and controlling NCDs. INCDDP is a form of community participation in activities for early detection, monitoring, and early follow-up of NCDs risk factors independently [7], routinely, integrated, and continuously [8]. The high number of PTM cases in Kendari City (Indonesia) requires serious handling by increasing the role of the Puskesmas through the Integrated Non-Communicable Disease Development Post (INCDDP), significantly expanding the role of cadres in the context of preventing and controlling PTM. INCDDP is a form of community participation in activities for early detection, monitoring, and early follow-up of PTM risk factors independently [7], routinely, integrated, and continuously [8].

In improving the skills of cadres, it is necessary to support the development of health workers, especially community nurses [9]. One of the intervention strategies that can be applied as community nurses as educators or educators is to provide health education to high-risk community groups and health cadres and change public health behavior. Following this research, nurses are expected to be able to empower cadres by increasing the knowledge and skills of cadres as mover in the community. One of the ways to increase knowledge and skills is through community-based education programs. This is intended to improve the quality of cadres in providing counseling and management to patients and families of NCDs patients, as well as the community [10–12].

The role of INCDDP cadres is as an implementer of NCDs risk factor control for the surrounding community. The functions of cadres are as coordinator of INCDDP implementation, community mobilizer to participate in INCDDP, monitoring of measurement of NCDs risk factors, counsellor for INCDDP participants, recorder of results of INCDDP activities [13].

There are still many problems in service at INCDDP related to the capacity of cadres. In theory, three factors affect a person's performance: individual elements consisting of abilities and expertise, background, and demographics. The second is psychological factors consisting of perceptions, attitudes, learning and motivation. The last is organizational factors, namely resources, leadership, rewards, structure and job design. These three factors can be classified into intrinsic factors, while extrinsic factors include political, economic and social factors [14].

The results of previous studies stated a relationship between cadre performance with attitudes, motivation, rewards, job design, and there was no relationship between HR and the role of stakeholders [15]. It is in line with other research states that the support of health cadres and family support by using INCDDP in the Ballaparang working area of Makassar City [16]. Kendari City has 15 PHCs, 13 of which have INCDDP. INCDDP cadres have a very big role in the prevention and early detection of risk factors for NCDs in the community [6].

The purpose of this study was to analyze the factors related to the performance of INCDDP cadres in Kendari City (Indonesia).

Materials and Methods

Trial design

This type of research is an observational analytic with a cross-sectional design to analyze the determinants of the proxy factors related to the performance of INCDDP cadres in Kendari City (Indonesia).

Participants

This research was carried out in October 2021 at 3 (three) Puskesmas in Kendari City (Indonesia) consisting of Abeli, Lepo-Lepo, and Perumnas Health Centers involving 56 INCDDP cadres with criteria including cadres who were present at the time of the study, cadres with active status participating in Integrated Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post (INCDDP) activities, while the inactive Cadres are expelled.

Intervention

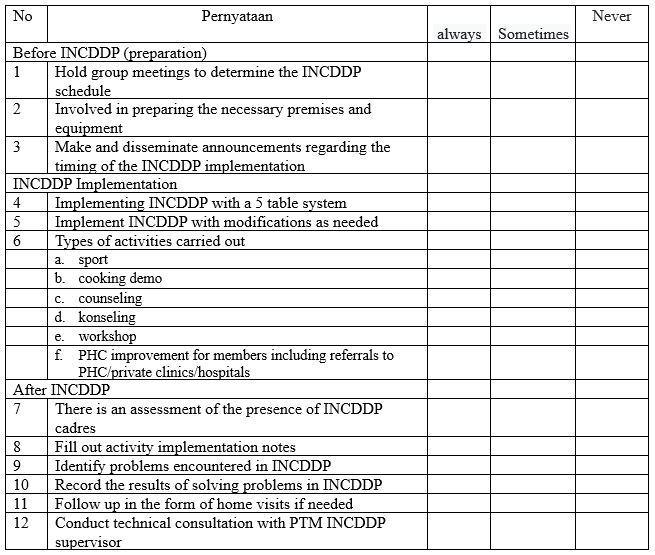

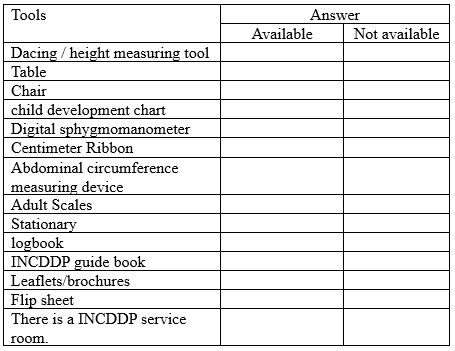

The dependent variable in this study is the performance of cadres with the objective criteria of "good" and "bad". While the independent variables are cadre training, infrastructure, knowledge, awards with "good" and "less" objective criteria. Collecting data on cadre performance variables using a questionnaire, and cadre training variables, infrastructure, knowledge, awards, also using questionnaires. on each variable, consisting of 10 questions with an alternative scoring as follows: if the respondent answers yes then it is given a score of 1 and if the respondent answers no it is given a score of zero. All questionnaires in this study used previous research questionnaires that had been tested for validity and reliability. The questionnaire received an award from the Kiting PR research. et al, [15], questionnaire of knowledge, training and infrastructure adoption from Handayani RO. et al, research [17].

Outcomes

Knowing the performance of cadres, training history, rewards, infrastructure, and knowledge.

Sample size

The number of participants in this study was 56 people. The age of the sample in this study was between 26-67 years, all of whom were female because all Integrated Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post (INCDDP) cadres were female. The sampling method in this study was total sampling because the number of Integrated Non-Communicable Diseases Development Post (INCDDP) candidates was very small.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with Interquartile Range (IQR). The bivariate analysis uses the chi-square test, and multivariate uses logistic regression. Logistic regression test is used because the data scale used is categorical or binomial. in the multivariate test, there is R2 or R square also referred to as the coefficient of determination which explains how far the dependent data can be explained by independent data. All tests with p-value (p)<0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 16.0 application.

Ethical Consideration

No economic incentives were offered or provided for participation in this study. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical considerations of the Helsinki Declaration. This study obtained ethical feasibility under the Health Research Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine, Halu Oleo University, number: 183/UN29.17.1.3/ETIK/2021.

Result

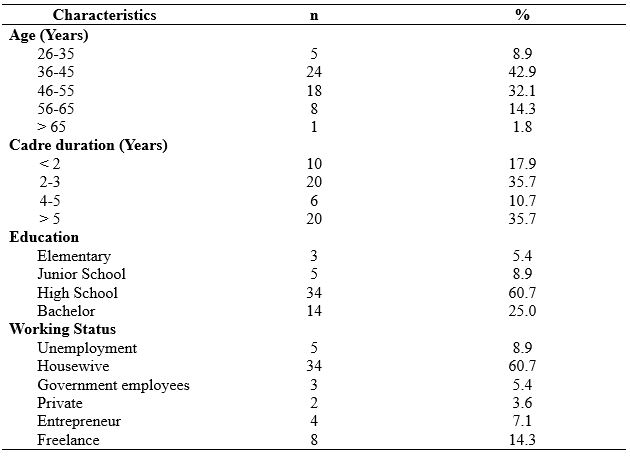

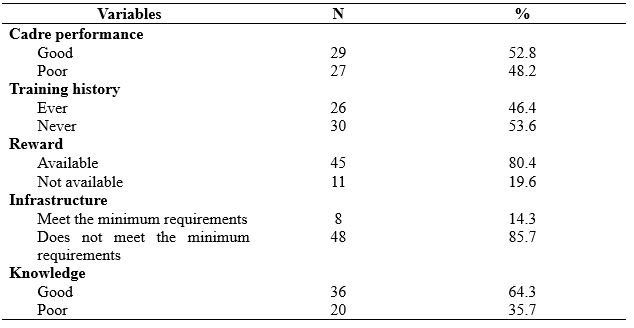

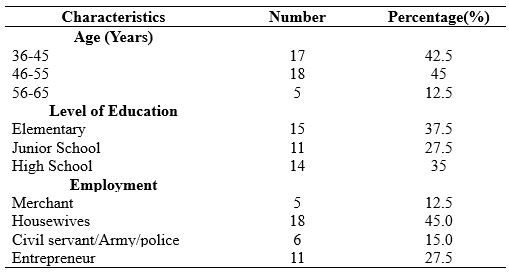

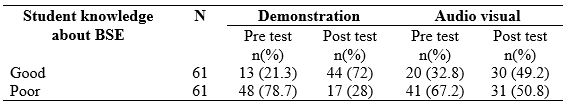

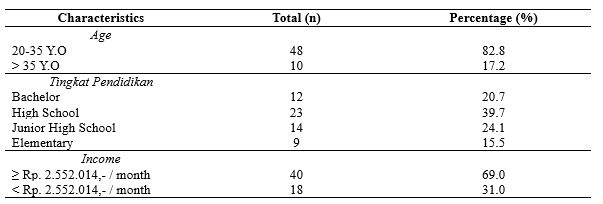

The distribution of the characteristics of the results of this study is showed in Table 1:

Table 1. Frequency Distribution Based on Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of 56 respondents based on age characteristics, primarily aged 36-45 years as many as 24 (42.9%), the highest length of being a cadre is 2-3 years, and > 5 years each is 20 (35.7%), the highest level of education is high school graduates as many as 34 (60.7%). The most elevated employment status is as a housewife as much as 34 (60.7%).

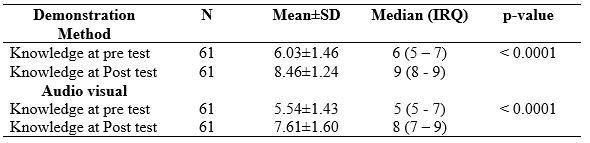

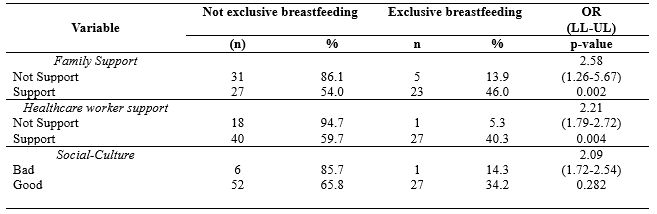

The distribution of research variables is presented in table 2. Table 2 shows the frequency, distribution by knowledge, perception of vulnerability, and compliance, there were 29 cadres (52.8%) who performed well, 26 cadres (46.4%) had attended training, 45 cadres (80.4%) stated that they had received awards, there were 48 cadres (85.7%) who indicated that infrastructure facilities were not available. Meet the minimum requirements, and 36 cadres (64.3%) have good knowledge.

Table 2. Frequency Distribution by Knowledge, perception of vulnerability, and compliance

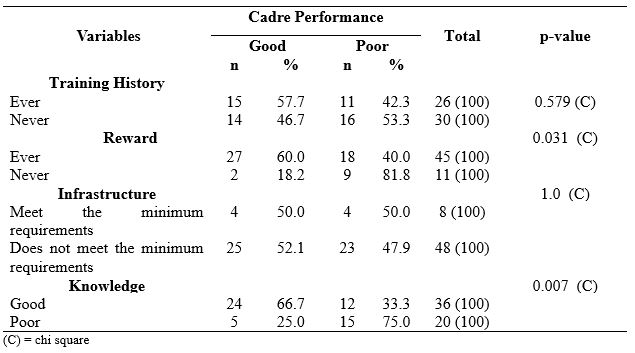

The distribution of the relationship between research variables can be presented in the following table 3:

Table 3. Relationship between variables

Table 3 shows that of the 26 respondents who have a good training history, there are 15 cadres (57.7%) who perform well and 11 cadres (42.3%) who perform poorly, then from 30 respondents who have a history of lack of training, there are 16 cadres (53.3%). Underperforming and 14 cadres (46.7%) performed well. The chi-square test showed a p = 0.579, indicating no significant relationship between training history and the performance of INCDDP cadres.

Forty-five respondents assessed the availability of the award, as many as 27 cadres (60.0%) with good performance and 18 cadres (40.0%) with less performance. Then from 11 respondents who assessed that the award did not exist, nine cadres (81.8%) with poor performance and two cadres (18.2%) performed well. The chi-square test shows the p = 0.031, indicating a significant relationship between rewards and the implementation of INCDDP cadres.

Eight respondents assessed the minimum requirements of infrastructure, four cadres (50.0%) with good performance and four cadres (50.0%) with poor performance. Of the 48 respondents who assessed that the infrastructure did not meet the minimum requirements, 23 cadres (47.9%) underperforming and 25 cadres (52.1%) performed well. The chi-square test shows that the p = 1.0 indicates no significant relationship between infrastructure and the performance of INCDDP cadres.

Of the 36 respondents who have good knowledge, there are 24 cadres (66.7%) with good performance and 24 cadres (33.3%) with poor performance; then from 20 respondents who have less knowledge, there are 15 cadres (75.0%) with poor performance and five cadres (25.0 %) perform well. The chi-square test showed a p = 0.007, indicating a significant relationship between knowledge and performance of INCDDP cadres.

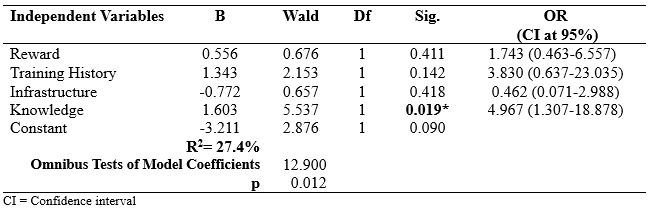

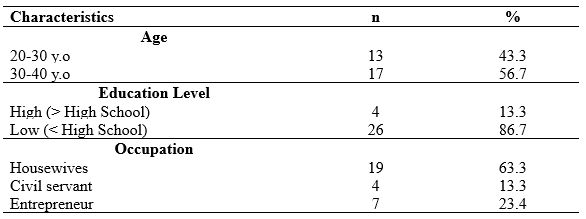

Multivariate data analysis using logistic regression test is presented in table 4.

The results of the multivariate analysis showed that the Wald value of the knowledge variable was the largest with a significant value (p = 0.090).

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of INCDDP Cadre Performance

The value of R2 = 27.4% indicates that this model can explain the effect variable (INCDDP cadre performance) of 27.4%, while 72.6% is influenced by other variables not examined.

The value of chi square = 12,900 with sig. 0.012 in Degree of Feedom 4 the value of chi square table = 9.49. it can be seen that the p value < 0.05, so it can be ascertained that the addition of the independent variable has a real effect on the model, in other words other models are declared FIT

Discussion

1.Reward

The purpose of this study was to analyze the factors related to the performance of INCDDP cadres in Kendari City (Indonesia). The existence of cadres should receive fair and sincere recognition and appreciation [18]. Recognition of the existence of cadres from cadre coaches in the sub-district needs to be realized by prioritizing free health services and the presence of cadre uniforms [19]. The hierarchy of human needs starts from primary needs (physiological needs and safety needs) to be dominant until these needs are felt to be sufficiently fulfilled [20].

Appreciation for the work done is a desire from selfish needs, manifested in praise, gifts (in the form of money or not), announced to his co-workers [21]. Therefore, giving awards for cadre loyalty will be very helpful to maintain the activeness of Posbindu cadres; giving tasks that are not boring with praise, completing attributes while on duty will increase cadre performance [22].

In this study, it was found that of the overall respondents, more than half had received awards from the government through the Puskesmas or the Kendari city health office. Indeed, this greatly influenced the motivation of Posbindu cadres in working. It is statistically proven that cadres who have a history of receiving awards tend to perform well and vice versa.

It is stated that usually, a person will feel mistreated if the treatment is seen as a dangerous thing. In working life, this perception is associated with various things, namely incentives and the number of hours worked [23]. The provision of incentives is a basic payment to motivate employees to be more advanced in work with more excellent skills and responsibilities [24]. Incentives are one type of award that is associated with work performance [25].

The award should be given to human resources, in this case, Posbindu PTM cadres who perform well to increase the spirit of work. Other cadres will see and will encourage other cadres to work better so that performance improves. Therefore, the performance of PTM Posbindu cadres will significantly increase if awards are given to their human resources.

In line with the findings of Renate Pah Kiting [15] stated that there is a relationship between rewards and performance (p=0.013 OR=10.400). Furthermore, Renate et al. said that cadres who received awards ten times would have the opportunity to have better performance compared to cadres who did not accept awards.

2.Training

The commitment of cadres to the responsibilities and functions of the INCDDP program in the Anambas Islands is quite good. It is evidenced by the continued implementation of the INCDDP program even though it is still constrained by several problems such as limited tools and materials and has never received special training. Therefore, support and commitment from cadres are very vital in the implementation of the INCDDP program. In the results of his research, it is stated by [26] that INCDDP cadres who always consistently run INCDDP with or without training will motivate other cadres to take an active role and try to help active cadres with what has been exemplified.

In this study, only a few respondents had ever been sent to receive training, although some of the cadres who had attended the training section stated that they were not under the assignment field at INCDDP. This condition will undoubtedly affect cadres' performance where when doing work. They do not look professional due to their lack of knowledge.

There is a difference in the proportion of cadres who received training and whose performance was considered "good" compared to cadres whose performance was "good" but did not receive training. The result shows that the more often cadres attend training, the better their performance [27]. Cadre training is carried out to increase the knowledge and skills of cadres. It will be achieved if the training section is carried out correctly. Puspasari A stated that the quality of cadre training is a factor causing cadres' low knowledge and skills level in carrying out their roles and duties. Therefore, training activities should be carried out regularly with a distance that is not too long.

The training should always start with the importance of an INCDDP cadre's goals so that interest and strong desire to make decisions and take action in implementing PTM Posbindu activities arise. It is expected that cadres will work with higher motivation and feel satisfied with their work so that it has a direct impact on increasing performance [28].

3.Infrastructure

Not all of the INCDDP in the working area of the PHC have complete kits; it requires them to use alternate tools at implementation. The Posbindu kit contains tools for checking blood sugar, cholesterol, uric acid, measuring height and then a body fat analyzer. Digital devices have never been calibrated, and this, of course, has fatal consequences in calculating the inspection results. Based on the inspection, the digital sphygmomanometer is broken, which give abnormal results in measurement.

Regarding the damaged digital INCDDP equipment, it is also following the research of Astuti et al. [29] that the number of NCDs INCDDP equipment is damaged/error. These tools include; body fat scale analyzer, measuring blood sugar and measuring total cholesterol. Likewise, research by Pranandari et al. [30] concluded that the infrastructure for the NCDs Posbindu in Banguntapan District, Bantul Regency for examining NCDs risk factors in the form of examination strips was not sufficient. Nova Silviyani's research [31] states that the statistical results obtained a p of 0.05 = (0.05), so it can be noted that there is no significant relationship between infrastructure and Posbindu performance.

In motivating the work, it should provide suitable facilities and infrastructure to carry out tasks. However, as complained by the cadre coach at the Kendari City District level, inadequate facilities and infrastructure such as tables, chairs, scales, stationery and especially the Posbindu place will hinder the performance of Posbindu cadres [32].

Posbindu activities will not be able to run correctly if adequate facilities do not support them. The provision of work facilities is that the work facilities provided must be sufficient and follow the duties and functions. Moreover, it must be implemented and available at the right time and place. Therefore, Posbindu facilities are everything that can support the implementation of Posbindu activities such as a fixed place or location, routine funds for giving additional food (PMT), the necessary tools, for example, kitchenware, KMS, tables, chairs, register books and others [33].

4.Knowledge

Knowledge of health cadres is an essential factor in supporting the ability of cadres to provide services. This study shows that several cadres have a low level of knowledge. There needs to be an effort to increase the knowledge of cadres, where one of the steps that can be taken is to provide health education and training to health cadres [34],[35].

Cadre knowledge is the extent to which cadres understand their duties and roles in INCDDP activities, including preparation before implementation, during implementation and after the implementation of INCDDP for the elderly. Knowledge of health cadres about INCDDP services is obtained from the information they obtain both from official sources, meaning from the health office that fosters them, from informal sources, and activities aimed at increasing cadre knowledge such as training, seminars and so on [36].

It is evident from the results of statistical tests that there is a relationship between knowledge and the performance of Posbindu cadres in the working area of the Puskesmas in Kendari City. Hence, there is a tendency for cadres who have an excellent ability to do their jobs well.

It is in line with research [37] which examines the relationship between knowledge and length of work with the skills of cadres in assessing the growth curve of toddlers at the Posyandu, Tegalsari Village, Candisari District, Semarang City. This study shows that the level of knowledge of cadres about the growth curve of toddlers is primarily adequate, where one of the factors related to this knowledge is the level of education of cadres, most of whom are in high school.

We assume the level of education of cadres varies from elementary school to high school level. This level of schooling dramatically affects the attitude and ability of cadres in capturing information conveyed by officers both when training and visits to INCDDP.

5.Multivariate test results

In Table 4, there is a significant positive correlation between the Performance and Knowledge of INCDDP Cadres (OR=4.987; p=0.019). it can be explained that after going through a simultaneous test between the performance of cadres and all independent variables (knowledge, training, infrastructure, and awards) it was found that only the knowledge of cadres was significant while the other 3 variables were not significant. Knowledge of cadres dominates the motivation of cadres to improve their performance, so even though infrastructure is available, if cadres do not have knowledge of what to do, then cadres' performance tends to be poor.

Implications of research results for nursing and clinical practice is to be valuable information for health service providers, especially community health centers to maximize the performance of nurses in assisting cadres when providing services to the community.

Conclusion

Cadre performance is related to awards, cadre training history, infrastructure and cadre knowledge. The most related factor to INCDDP cadre performance is cadre knowledge.

There is a need to increase advocacy to the legislative body regarding the importance of getting more budget for PHC and the need to improve health funds budgeted through the Regional Revenue and Expenditure Budget (APBD) to support the implementation of services and the need to formulate regulatory policies to tackle financing for cadres immediately. It is necessary to carry out periodic training for cadres, and it is hoped that INCDDP cadres will continue to explore knowledge and experience to improve performance in the implementation of INCDDP activities and always be positive in every action carried out at INCDDP and need to improve and improve facilities and infrastructure to meet basic service needs.

Limitations of Study

The limitations of this study include the very limited number of subjects, and this research only involves one region or 1 region so the results may be different when compared to other regions or regions in Indonesia.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Chairperson of the research institute and community service who have supported this research.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Competing interests statement

There are no competing interests for this study.

References

- Kemenkes RI. Rencana Aksi Nasional Penyakit Tidak Menular 2015-2019. Kementerian Kesehatan RI. Jakarta; 2017.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization. Italia; 2010. 176 p.

- WHO. Noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization; 2018.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Riset Kesehatan Dasar. Jakarta: Balitbangkes RI; 2018. Available from: https://kesmas.kemkes.go.id/assets/upload/dir_519d41d8cd98f00/files/Hasil-riskesdas-2018_1274.pdf “Accessed December 21,2021”

- Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Sulawesi Tenggara. Profil Kesehatan Propinsi Sulawesi Tenggara. Kendari: Bidang P2PL Dinas Kesehatan Prov. Sultra; 2020. Available from: https://farmalkes.kemkes.go.id/ufaqs/dinas-kesehatan-provinsi-sulawesi-tenggara/“Accessed December 28,2021”

- Dinas Kesehatan Kota Kendari. Profil Dinas Kesehatan Kota Kendari. Kendari: Bidang P2PL Dinas Kesehatan Kota Kendari; 2019. Available from: https://siasiksehat.kendarikota.go.id/profil-kesehatan-kota-kendari/“Accessed December 21,2021”

- Dinkes Kabupaten Demak. Kegiatan Posbindu PTM. Demak; 2018. Available from: https://dinkes.demakkab.go.id/download/“Accessed December 21,2021”

- Kemenkes RI. Petunjuk Teknis Pos Pembinaan Terpadu Penyakit Tidak Menular (POSBINDU PTM). In Jakarta: Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Penyakit dan Penyehatan Lingkungan Direktorat Pengendalian Penyakit Tidak Menular; 2012.

- Iriarte‐Roteta A, Lopez‐Dicastillo O, Mujika A, Ruiz‐Zaldibar C, Hernantes N, Bermejo‐Martins E, et al. Nurses’ role in health promotion and prevention: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(21–22):3937–49.

- Halcomb E, Williams A, Ashley C, McInnes S, Stephen C, Calma K, et al. The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of nursing management. 2020;28(7):1553–60.

- Halcomb E, McInnes S, Williams A, Ashley C, James S, Fernandez R, et al. The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2020;52(5):553–63.

- Blay N, Sousa MS, Rowles M, Murray‐Parahi P. The community nurse in Australia. Who are they? A rapid systematic review. Journal of nursing management. 2021;

- Kementerian Kesehatan RI. Modul Pelatihan Posbindu PTM. Jakarta: Direktorat PPTM, Direktorat Jenderal PP dan PL; 2013.

- Andriani K, Bisri RS MS. Analisis Faktor Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Kinerja Tenaga Kesehatan Pada Penerapan Program Keluarga Sadar Gizi di Kabupaten Sukoharjo. Manajemen Bisnis Syariah. 2013;1(7).

- Kiting RP, Ilmi B, Arifin S. Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Kinerja Kader Posbindu Penyakit Tidak Menular. Jurnal Berkala Kesehatan. 2017;1(2):106.

- Nasruddin NR. Faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi pemanfaatan pos pembinaan terpadu penyakit tidak menular (POSBINDU PTM) Di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Ballaparang Kota Makassar Tahun 2017. Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar; 2017. Available from: http://repositori.uin-alauddin.ac.id/6515/1/NURIZKA RAYHANA_opt.pdf.“Accessed December 28,2021”

- Handayani RO, Suryoputro A, Sriatmi A. Faktor-Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Praktik Kader Dalam Pelaksanaan Posyandu Lansia di Kelurahan Sendangmulyo Kecamatan Tembalang Kota Semarang. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat (Undip). 2018;6(1):81–92.

- Husniyawati YR, Wulandari RD. Analisis motivasi terhadap kinerja kader Posyandu berdasarkan teori Victor Vroom. Jurnal Administrasi Kesehatan Indonesia. 2016;4(2):126–35.

- Bunawar KMS. Hubungan Penghargaan, Tanggung Jawab, Pengawasan, Hubungan Interpersonal terhadap Motivasi Kerja Kader Posyandu di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Sungai Bengkal Kabupaten Tebo Tahun 2017. Scientia Journal. 2019;8(1):249–55.

- Tay L, Diener E. Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2011;101(2):354.

- Profita AC. Beberapa faktor yang berhubungan dengan keaktifan kader posyandu di Desa Pengadegan Kabupaten Banyumas. Jurnal Administrasi Kesehatan Indonesia. 2018;6(2):68–74.

- Isaura V. Faktor-faktor yang berhubungan dengan kinerja kader posyandu di wilayah kerja Puskesmas Tarusan Kecamatan Koto XI Tarusan Kabupaten Pesisir Selatan tahun 2011. Padang: Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Andalas (skripsi tidak diterbitkan). 2011; Available from: http://repository.unand.ac.id/17532/1/FAKTOR.pdf. “Accessed December 20,2021”

- Siagian SP. Manajemen Sumber Daya Manusia. Jakarta: Bumi Aksara; 2006.

- Bangung W. Manajemen sumber daya manusia. Bandung: erlangga. 2012;

- Larasati S. Manajemen Sumber Daya Manusia. Deepublish; 2018.

- Primiyani Y, Masrul M, Hardisman H. Analisis Pelaksanaan Program Pos Pembinaan Terpadu Penyakit Tidak Menular di Kota Solok. Jurnal Kesehatan Andalas. 2019;8(2):399.

- Puspasari A. Faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi kinerja kader posyandu dikota Sabang Provinsi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam. Skripsi. Institut Pertanian Bogor; 2002. Available from: https://repository.ipb.ac.id/handle/123456789/14771. “Accessed December 20,2021”

- Handarsari E, Syamsianah A, Astuti R. Peningkatan Pengetahuan dan Ketrampilan Kader Posyandu di Kelurahan Purwosari Kecamatan Mijen Kota Semarang. In: PROSIDING SEMINAR NASIONAL & INTERNASIONAL. 2015. Available from: https://jurnal.unimus.ac.id/index.php/psn12012010/article/view/1646. “Accessed December 25,2021”

- Astuti ED, Prasetyowati I, Ariyanto Y. Gambaran Proses Kegiatan Pos Pembinaan Terpadu Penyakit Tidak Menular di Puskesmas Sempu Kabupaten Banyuwangi (The Description of Activity Process for the Integrated Development Post of Non-Communicable Disease (IDP of NCD) at Sempu Public Health Centre i. Pustaka Kesehatan. 2016;4(1):160–7.

- Pranandari LL, Arso SP, Fatmasari EY. Analisis implementasi program pos pembinaan terpadu penyakit tidak menular (posbindu PTM) di Kecamatan Banguntapan Kabupaten Bantul. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat (Undip). 2017;5(4):76–84.

- Silviyani N, Setyawati VAV. Faktor-Faktor yang Berhubungan dengan Kinerja Posyandu Lansia di Wilayah Puskesmas Miroto Semarang. Skripsi Semarang: Universitas Dian Nuswantoro. 2015; Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35382833.pdf. “Accessed December 2,2021”

- Syahmasa. Analisis Hubungan Faktor Demografi dan Motivasi Dengan Kinerja Kader Dalam Berperan Serta Meningkatkan Pelyanan Keperawatan Di Posyandu Wilayah Puskesmas Kecamatan Cipayung Jakarta Timur Tahun 2002. 2002. Available from: https://lib.ui.ac.id/detail?id=72143&lokasi=lokal. “Accessed December 2,2021”

- Siagian S. Teori dan Praktek Kepimpinan. Jakarta: PT. Rineka Cipta; 2003.

- Nurhidayah I, Hidayati NO, Nuraeni A. Revitalisasi Posyandu melalui Pemberdayaan Kader Kesehatan. Media Karya Kesehatan. 2019;2(2).

- Lindner JR, Dooley KE. Agricultural education competencies and progress toward a doctoral degree. Journal of Agricultural Education. 2002;43(1):57–68.

- Jayusman TAI, Widiyarta A. Efektivitas Program Pos Pembinaan Terpadu (POSBINDU) Penyakit Tidak Menular (PTM) Di Desa Anggaswangi Kecamatan Sukodono Sidoarjo. Dinamika Governance: Jurnal Ilmu Administrasi Negara. 2017;7(2).

- Syamsianah A, Winaryati E. Hubungan Pengetahuan dan Lama Kerja Dengan Ketrampilan Kader Dalam Menilai Kurva Pertumbuhan Balita di Posyandu Kelurahan Tegalsari Kecamatan Candisari Kota Semarang. Jurnal Gizi. 2013;2(1).

Appendix A

QUESTIONNAIRE

Instruction :

1. Fill in the blanks with honest answers

2. Put a tick (X) on the multiple choice answer

3. Put a tick (√ ) on the available answer choices

A. Cadre performance

B. INCDDP Cadre Training

Have you ever received training for INCDDP cadres?

a. Yes

b. No

C. Awards

1. Have you ever received an award in the form of a charter or award while being a INCDDP cadre?

a. Yes

b. No

2. Have you ever received an award in the form of funds while being a INCDDP cadre?

a. Yes

b. No

3. Do you get a uniform to carry out INCDDP activities?

a. Yes

b. No

4. Do you always receive an award if you are active in INCDDP activities?

a. Yes

b. No

D. Facilities and infrastructure

E. Knowledge

PROBLEM BASED LEARNING MODEL IN VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENT CLASS IN HEALTH: A SISTEMATIC REVIEW

Rosmaria1, Rayandra Ashar2, Muhaimin3, Herlambang4

1Department of Midwifery, Health Polytechnic of Jambi, Indonesia

2Chemistry Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Indonesia

3Study Programs In Chemistry Education, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Jambi University, Indonesia

4Medical Study Program, Faculty of Medicine, Jambi University, Indonesia

* Corresponding author: Rosmaria, Department of Midwifery, Health Polytechnic of Jambi, Indonesia. , E-mail: rosmaria.poltekkes@gmail.com

Cita questo articolo

Abstract

Background. PBL is a student-centred learning method where students determine their own learning goals from clinical-based problems. Many studies have been conducted regarding the effectiveness of PBL based on virtual classes or online classes in various fields of science. This systematic study aims to evaluate the implementation of PBL in various online learning contexts.

Methods. This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. We include intervention studies, training, or educational strategies using PBL method focusing on any health student class, and published between 2010 to 2021. Three authors (RA, MH, HR) performed data extraction. Differences that arise are resolved by consensus, in consultation with other investigators (RS).

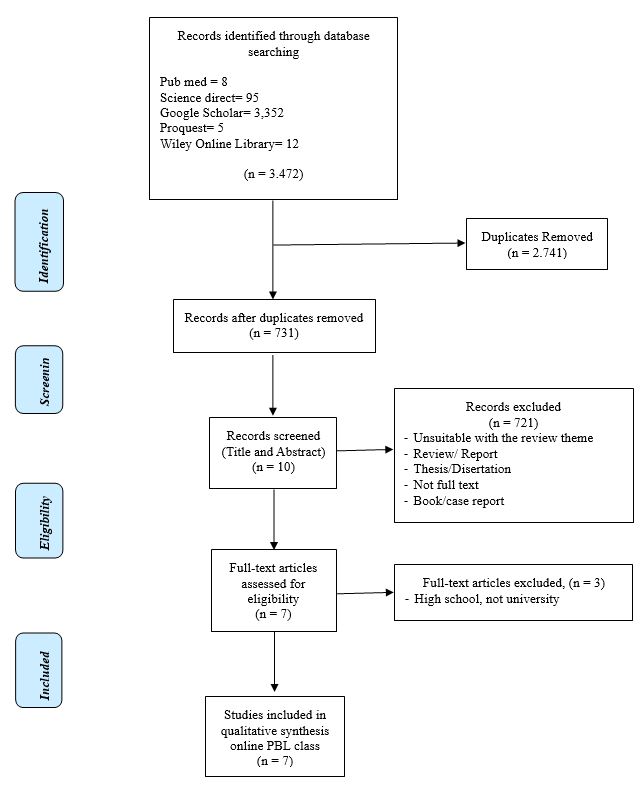

Results. The search returned 1,678 articles; after removing the duplicated articles, 731 articles remained, of which 721 articles were removed after screening titles and abstracts. The remaining ten articles were reviewed and checked for eligibility, so three articles were excluded. The final results were collected as many as seven articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Conclusion. Online PBL is perceived to be an effective educational strategy by lecturer. Overall, the results for PBL in online/virtual class include Positively impact the learning experience, Increase knowledge and skills, improve the learning process, Increased self-learning capacity, motivation, self-monitoring, and interpersonal communication, Improve student understanding and application of theoretical knowledge in a large classroom setting, Increased availability and acceptance, reduced interactivity.

Keywords: Problem-Based learning, Virtual, Online Class, Students

INTRODUCTION

As a modern pedagogical philosophy, Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is increasingly recognized as a critical research area in student learning and pedagogical innovation in health science education [1,2]. In contrast to teaching and learning approaches dominated by conventional lectures, inquiry-based approaches such as PBL encourage students to be actively involved in knowledge construction and develop competencies in various contexts [3]. This review focuses on PBL rather than other inquiry-based pedagogical approaches, such as discovery learning, experiential learning, and project-based learning. Given the high level of technological involvement of 21st-century learners, a new area of research is examining the emerging role of educational technology in PBL [4–6]. Therefore, this study aims to review the application of PBL in the concept of problem-based online classes. What is interesting from this review are studies investigating the effectiveness of online classes in achieving PBL-related student learning outcomes of flexible knowledge, practical problem-solving skills, independent study skills, collaborative teamwork skills, and intrinsic motivation [7,8].

The studies included in this review are studies where educational technology has been adopted to support PBL for undergraduate and postgraduate program learning. Traditional pedagogy, which is teacher-centred, class-oriented, and pressure on exams, places students passively “acceptance” state [9]. PBL is a student-centred learning method where students determine their own learning goals from clinical-based problems [10,11]. As an established approach, PBL has been reported to be suitable for use in graduate medical schools [12]. Recently, PBL has become a subject of considerable interest in postgraduate education. PBL can cultivate postgraduate leadership, teamwork, communication, and problem-solving skills, which are helpful for lifelong learning and facilitate postgraduates to take responsibility for their learning.

The online PBL format has been piloted with varying degrees of success, and although the PBL approach is beneficial for students in various disciplines, the results associated with this strategy are inconclusive in nursing education [13]. One such study compared conventional classroom-based strategies with problem-based asynchronous learning for part-time public health students. The development of web-based technology has resulted in new ways to implement PBL in large classrooms [14]. New teaching methods facilitated by web-based technologies have been applied in nursing education using web-based PBL methods with promising effects. Web-based PBL also enables better communication between teachers and students. When used with conventional PBL teaching methods, web-based PBL facilitates the development and promotion of more significant self-directed learning and innovation in nursing and other professional education systems.

Many studies have been conducted regarding the effectiveness of PBL based on virtual classes or online classes in various fields of science. It has prompted the author's interest to conduct a systematic study of this review on PBL implementation based on online classes or virtual classes. For this reason, the current study aims to evaluate the implementation of PBL in various online learning contexts.

METHODS

Review Protocol

This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [15]. The current study tries to evaluate the application of the problem-based learning method in virtual or online learning situations from articles that have been published in the period 2010 to 2021.

Searching strategy

Relevant articles were searched and collected using Sciencedirect, Google Scholar, Proquest, Pubmed, and the Wiley Online Library, with a publication time between 2010 and 2021. The search keywords were adjusted according to the Mesh terms for health research. The keywords used vary, depending on the search engine used. In general, the keywords focus on 'Effectiveness' OR 'Effect' OR 'Evaluation' AND 'Problem-Based Learning' OR 'PBL' AND 'Online class' OR 'Virtual class' OR 'virtual meeting' AND 'web-based' OR 'social-media OR 'Online group discussion'.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria consist of intervention studies, training, or educational strategies using PBL method focusing on any health student class in certain subjects for example Physiology, anatomy, nursing care, community health, etc. Study outcomes such as increased knowledge, attitude, skills, and/or student satisfaction. We choose only articles published in English, and in the time range 2010 to 2021. We excluded or not reviewed books, disertation, letter to editor, and systematic review study.

Study Quality

Overall articles were assessed using the NIH (National Institutes of Health) quality assessment of controlled intervention studies, for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, and Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies [16].

A scoring sheet was developed to assess the research methodology and adherence to the scoring criteria for each article that met the inclusion criteria of this study. Articles with scores <30% of the criteria were classified as "poor", scores between 30 and 70% were classified as "moderate", and scores >70% were classified as "good" study quality. The articles taken are classified as moderate and "good".

Extraction and Analysis

Three authors (RA, MH, HR) performed data extraction. Differences that arise are resolved by consensus, in consultation with other investigators (RS) if an agreement is not reached. Main items extracted included: lead author/year, country, purpose of the study, method (Quasi-experimental, Randomized Controlled Trial), evaluation strategies, and results.

Titles and abstracts are screened on each database. Screening for duplicate articles is carried out using the Mendeley application. Substantive information is extracted from each article into a Microsoft Word table.

The author determined the selection of articles after being reviewed from 7 full-text articles adjusted to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data extraction was carried out with care. The interpretations are presented in the table by taking the critical parts of the article.

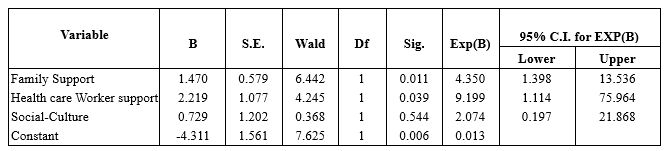

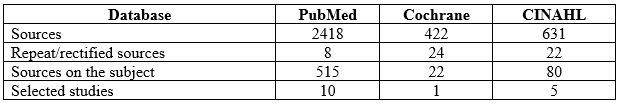

RESULTS

The search returned 1,678 articles; after removing the duplicated articles, 731 articles remained, of which 721 were removed after screening titles and abstracts. The remaining ten articles were reviewed and checked for eligibility, so three articles were excluded. The final results were collected as many as seven articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Article Characteristics

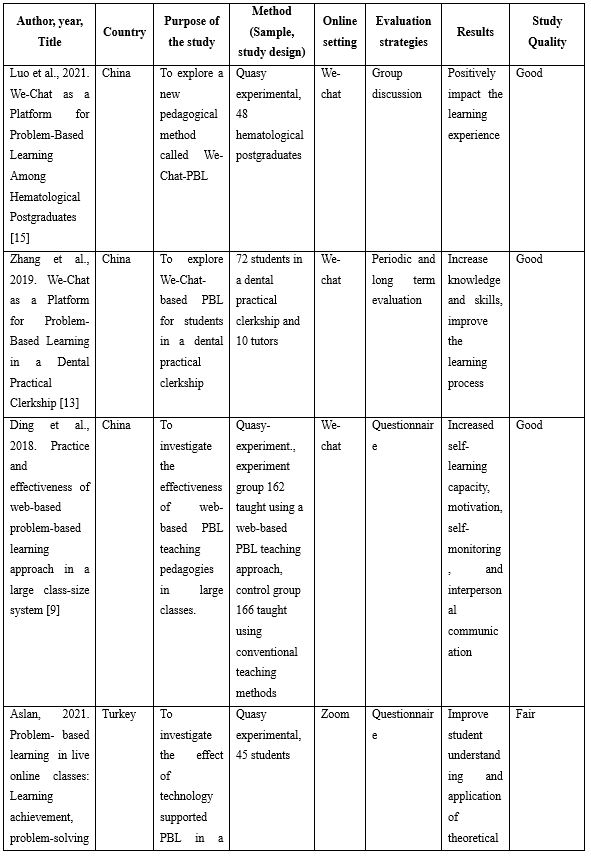

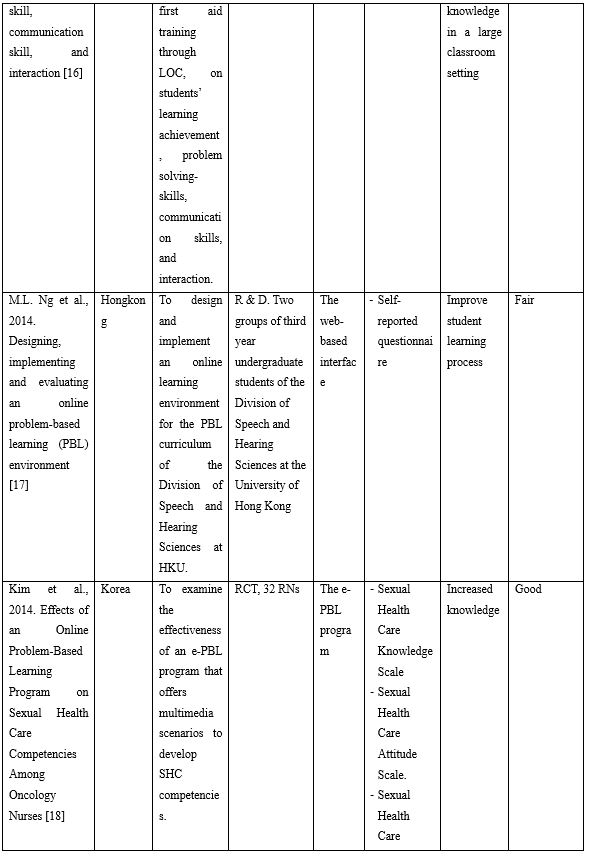

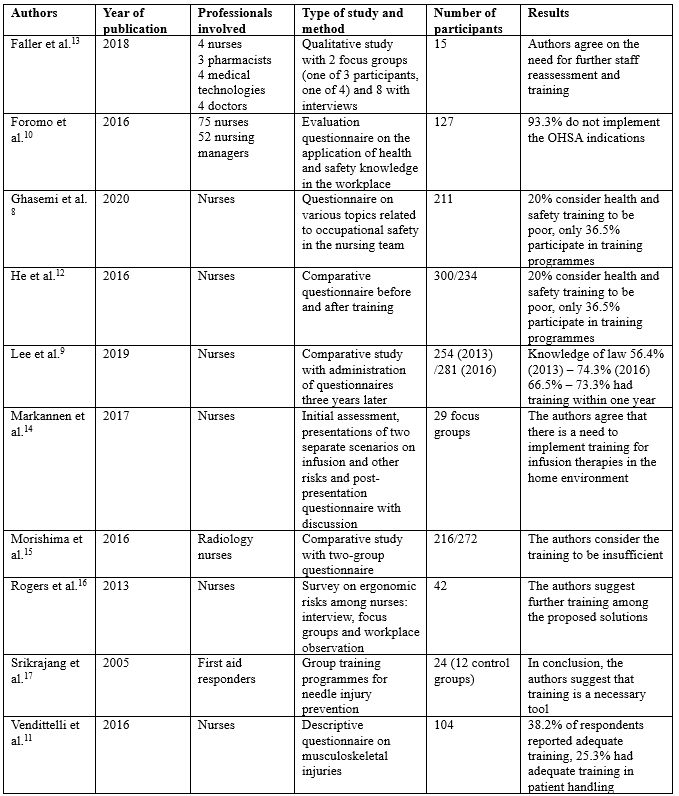

Most of the literature included is in the quantitative type with a Quasy experimental research design of five articles [13,17,18,21,22] and one each for the Randomized Controlled Trial [20], and Research & Development [19]. A total of 654 students were involved in all the studies included in this study. Included articles were published from 2010 to 2021 and conducted in five different countries, including China (n = 3) and one study in Hong Kong, Turkey, Korea, and the USA.

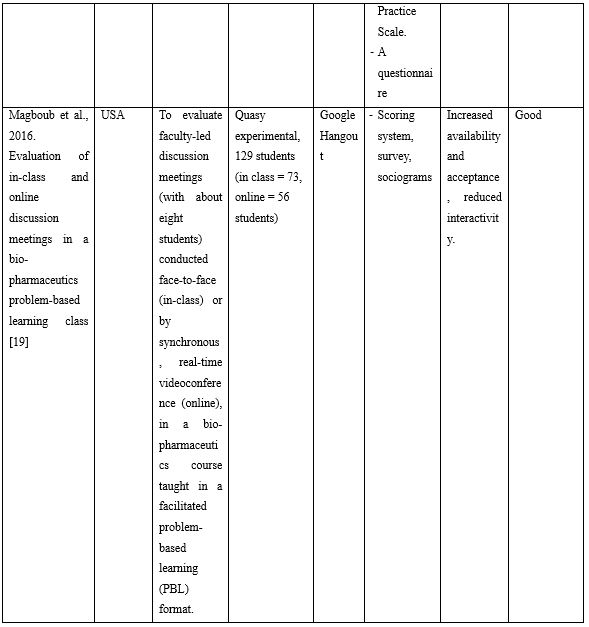

Areas of knowledge for the implementation of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in online classes include Hematology [17], Dentistry [13], Nursing management [22], problem-solving skills, and communication skills [18], Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences [19], Oncology Nurses [20], bio-pharmaceutics [21].

The educational levels of participants in several articles included in this review consist of clerkship students [13], Post-graduate students [15], undergraduate students, and working nurses [18].

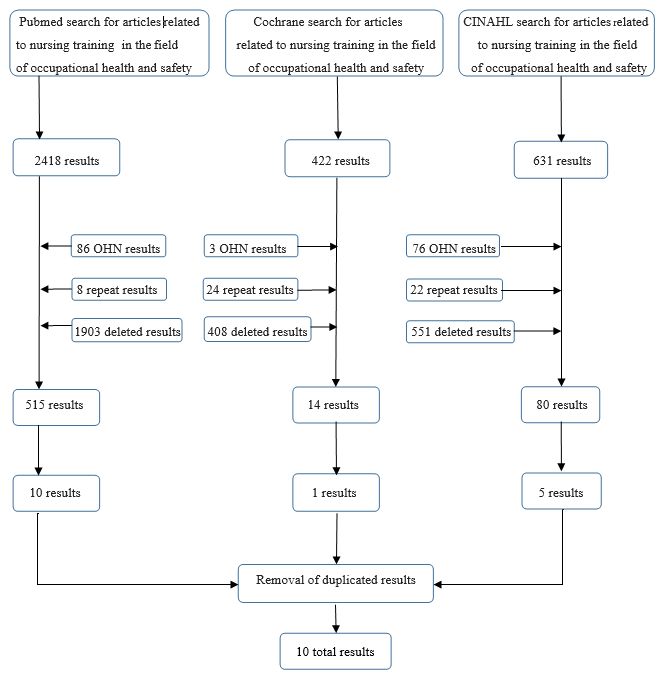

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart literature search

Table1. Critical data extraction from included articles

Online settings

The online class system used is varied, such as We-chat social media used in three studies conducted in China with results showing that this strategy provides an increase in the learning experience, increases student knowledge, and interpersonal communication [13,17,22]. Two studies conducted in the same year, namely 2014 in Hong Kong and Korea, used a web-based interface to form Adobe Connect and the e-PBL program. In carrying out the study, authors combined several other internet-based communication channels such as e-mail, and social media as a forum to discuss the assigned tasks where it improvises the learning process and can increase students' knowledge [19,20]. Meanwhile, a study in the USA used the Google Hangout application to discuss the tasks of the Problem-Based Learning program; this is considered the most accessible medium to use where this application is available on every gadget or smart phone. Through those media may increased availability and acceptance, but unfortunately reduced interactivity [21]. The application that is currently most often used is "Zoom" Aslan conducted a study that tried to investigate the effect of using this application in the PBL model on the problem-solving skills, communication skills, and interactions of 45 students involved in his studies. Zoom PBL improves student understanding and application of theoretical knowledge in a large classroom setting [18].

The entire study was conducted to assess the effect of implementing the PBL method in online classes. Some studies even compare with conventional methods or face-to-face [21]; [20]. Meanwhile, the study conducted by [18] tried to compare the online class with the PBL approach with the online class teacher-based methods. Three studies using We-chat applications in China aimed to assess the effectiveness of online class-based PBL using We-chat, but each has a different field of knowledge for its application [13,17,22].

DISCUSSION

The articles reviewed in this systematic review generally show the implementation of PBL methods in online classes. In some cases, this method can reduce cognitive load and allow students to learn in complex domains [18,20].

The We Chat-based PBL mode conducted by [17] is designed to support postgraduate students' abilities in haematology courses, including those related to clinical reasoning, team skills, and meta-cognition. This online PBL model has succeeded in eliminating the physical and temporal limitations of traditional PBL, as has been implemented so far [17]. Similar results were also obtained in another study that used We-Chat as a medium in the implementation of PBL, where this method succeeded in removing the physical and temporal limitations of traditional PBL in dental registrars. We-chat is very common and familiar in China, so this application is the primary choice for people to socialize in cyberspace. This method also ensures the time required and quality of PBL, expands the means of acquiring knowledge, and increases efficiency in problem-solving. As a modern pedagogical philosophy, the importance of PBL is increasingly recognized in student learning and innovation in medical education [1]. Many educators have tried to improve traditional PBL by modifying instruction. Therefore, other PBL modes such as tutors PBL, 3C3R Modified PBL, and Hybrid PBL have emerged in PBL teaching [13,23,24]. However, compared to traditional PBL, WeChat-PBL has several advantages that take PBL to a higher level [13,22].

M.L. Ng and colleagues used Adobe Connect to implement online tutorials to embody the Problem-Based Learning model for students. Users, namely students, can open any web browser to connect to Adobe Connect. All PBL sessions ran smoothly, without significant delays in audio or serious interruptions in video transmission. Students stated that Adobe Connect was smooth, easy to install and worked well with their home internet connection. The students agreed that the system met the requirements for online tutorials. The study also concludes that the pedagogical effectiveness associated with online PBL does not differ from traditional PBL for students in later years with the curriculum well integrated into the PBL process. Through online PBL, students enjoy PBL more and save a lot of travel time [19]. Thus, online PBL appears to be the way forward when time and place requirements cannot be met or when weather or other conditions do not allow for regular meetings or the current situation, namely the Covid-19 pandemic.

The e-PBL program that is trying to be developed in Korea shows that this program is very useful, especially for Oncology nurses. Online learning allows participants to interact with each other regardless of time and place restrictions and presents complex data in an accessible way that is fun and easy to learn. This program is highly expected to be integrated into continuing education for nurses. when PBL is delivered in online groups, students can play an active role in solving problems through the use of case studies and online discussions. Tutors participate in online discussions by contributing questions and comments, and provide timely feedback to encourage collaboration and topic-focused discussion [20].

The challenges of online education include technological capabilities, student acceptance of technology, and the ability of lecturers to adapt to new roles and to acquire new instructional skills [25]. The survey results in research in the USA show that technology is not a barrier for students. However, almost half of the students in the class indicated that they preferred discussion in class to online. Many students get lower online discussion learning scores than in class meetings [5]. PBL discussion meetings may be held online due to the increased availability and acceptance of technology but may lead to reduced interaction and participation. This suggests that online discussions require facilitators to encourage and stimulate student participation and active student-student interaction which may differ from the approach used for face-to-face class discussions [5].

The current reviews corresponds to the findings from other reviews focusing on the effectiveness of DPBL (Digital Problem Based Learning) in improving health professionals’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and satisfaction [1],[26]. These reviews explores more the differentiation between DPBL and traditional PBL [26]. In current review, we found few evidence that show the effectiveness of PBL in virtual environment similar with traditional PBL. Jin & Bridges reviews stated more on the hardware used in PBL, while our review mostly used software or application which commonly can be accessed using android technology in mobile phone.

CONCLUSION