Technological innovations in cardiac electrostimulation: Professional updating and cultural evolution of nurses

Carlo Uran1, Pasquale Piscitelli2, Mariuccia falco3, Giovanna Bombace3, Palma Eterno3

1 Interventional cardiologist. Cardiology and Intensive Care Unit, “San Giuseppe e Melorio” Hospital, Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Italy

2 Registered nurse. Cardiology and Intensive Care Unit, “San Giuseppe e Melorio” Hospital, Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Italy

3 Graduate nurse. Cardiology and Intensive Care Unit, “San Giuseppe e Melorio” Hospital, Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Italy

Corresponding author: Dr. Carlo. Uran, Cardiology and Intensive Care Unit, “San Giuseppe e Melorio” Hospital, Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Italy. Email: carlura@libero.it

Cita questo articolo

Abstract

Cardiology made enormous advances in the treatment of extremely severe diseases such as heart failure. Specifically, interventional cardiology has been enriched, over the years, with increasingly complex aids that have contributed in improving the quality of life and survival of patients suffering from this disease. These advances in technique compel the interventional cardiologist being constantly updated on new procedures and therapy. As a result, both the ward nurses and those supporting the cardiologist in the surgery room, must acquire the knowledge that allows them to be always in step with the fast-changing times.

The aim of this commentary is to underlining the importance of a continuous updating of nurses by emphasizing that their role has been changing over the years and that these professionals, along with the physicians, must stay up-to-date regarding technological innovations, within the limits of their specific skills.

Keywords: Heart failure; Cardiac Contractility Modulation; Nurse updating

Introduction

Nurses of interventional Cardiology unit must acquire more and more skills because of the evolution of technology and subsequently of the complexity of implantable devices. The acquisition of skills is a continuous process and requires constant effort. Therefore, not only the physician, who remains the main operator, must constantly update himself on new techniques and procedures, but also nurses who assist him in and out the operating room, must acquire the scientific mentality that allows them to get highly specialized technical knowledges. In the field of interventional cardiology, advances in technology made care approach increasingly complex, before, during and after an interventional procedure. In such a large and constantly evolving field, nurses should necessarily acquire all the skills for the assistance process and should consequently have the ability to analyze, decide and execute the most appropriate and safe care services, supported by solid evidence of effectiveness. Cardiac Contractility Modulation (CCM) therapy, delivered by OPTIMIZER SMART®, is part of the non-pharmacological therapy for treatment of heart failure with reduced or moderately reduced ejection fraction, in symptomatic patients (NYHA class II-IV) despite optimized medical therapy [1]. It is an important technological innovation for the treatment of this severe disease. The CCM acts by delivering a high-energy non-excitatory bipolar signal, synchronized with local electrical activity, in the ventricular absolute refractory period, by means of two active-fixation leads, placed on the IVS and spaced from each other by no more than 1 cm. Both leads can have a sensing and therapy delivery function. In the implantation phase, is very important to be meticulous in positioning the leads so that they have a sensing greater than 4 mV at the PSA. In the short and long term, this treatment increases left ventricular contractility. As result, the CCM therapy improves clinical status, functional capacity, quality of life and prevents hospital admissions of carefully selected patients [2]. The selection of the patient to whom implant this device, takes place by evaluating his quality of life and the frequency of hospitalizations for heart failure. Quality of life is assessed by the MLWHFQ questionnaire. A score over 30 in a patient in NYHA II class is indicative of severe lack of autonomy and is a significant element in the decision to implant such device (Fig. 1). The interventional procedure does not differ from those implemented for the implantation of other cardiac devices. The difference is about the periodic checking of the implanted device, performed by the cardiologist with the help of a biomedical engineer, who analyze the data by a portable computer loaded with a specific software, by which, electrical parameters and therapy delivery time are tested. The therapy delivery time must be at least 7 hours per day and a parameter to pay attention to is the percentage of therapy delivery, which must be as high as possible and not fall below 80%. [3].

Discussion

Many papers describe implantation procedure and the role of nurses [4-5-6]. After the surgery, nurse takes the patient back to the ward and performs an ECG. Nurses who record the ECG should be able to understand whether the device is properly working or not. The typical ECG of a patient implanted with a CCM device shows a ‘spike’ in the absolute refractory period of cardiac cycle: the ‘R wave’ of QRS complex. (Fig. 2). Nurses should know that the presence of a ‘spike’ on the ‘R wave’ of the QRS complex is not a non-capturing sign or a sensing defect: it is the proper operating of the device itself. This knowledge is important in order not to alarm the patient and inappropriately alert the cardiologist. The day after implantation, nurses should check the surgical wound, evaluate whether there is a hematoma or not and if medical attention is required. Then the patient can undergo to a chest x-ray to evaluate the position of the leads and to exclude a PNx, if the subclavian vein puncture has been performed without echo guide [7]. OPTIMIZER SMART® is powered by a weekly-rechargeable battery through an induction mini-charger, rechargeable itself, delivered to the patient. At bedside, physician and nurses instruct the patient, with the assistance of biomedical engineer, regarding its use. It is important, in this phase, that nurses as well assist the patient and reassure him about the easiness of device recharging procedure. Patient should charge the device battery weekly and it is advisable to suggest him to always recharging the device on the same day and at the same time, specifying however that it is not a life-saving device, but an electrical therapy provider. This avoids the worry of postponing or anticipating the charging process. Nurses get involved in many ways in interventional procedures: they manage the pre-operation care and technical setup; help the physician in the surgical room; check the correct functioning of the device and, if complications are detected, alert the physician and look for a quick solution to them. In order to perform these tasks, nurses should know how the device acts and which complications might occur after intervention, so they can be able to deal with them without any anxiety. In 2014 in order to assess critical care nurses' knowledge and practice regarding implantable cardiac devices in Egypt, was published a paper by which authors showed that Critical care nurses have inadequate knowledge and practice regarding implantable cardiac devices [8]. Unfortunately, things have not changed over the years. In 2017, in order to assess cardiology nurses' knowledge and confidence in providing education and support to ICD recipients, Steffes et al. published a paper. The result was surprising: authors proved that the ICD knowledge of US nurses in 2015 was similar to that reported in the United Kingdom in 2004 [9-10], with limited knowledge about the complexities of modern ICD devices. Such deficits in knowledge may affect the quality of education provided to ICD recipients in preparing them to live safely with an ICD. A survey published in 2021 by Fitzimons et al, showed that many nurses felt not being living up to their job and emphasize the importance of in continuing cardiovascular nursing education and of their professional updating[11]. Nowadays, the nurses should be a complete professional and should have the technical and care skills required to obtain the best result in interventional procedures, as regard the new generation devices as well. Consequently, the interventional cardiology/electrostimulation nurses are required to have not only care skills, but also the knowledge of devices. In CCM therapy, electrical stimulation is delivered to the cardiac muscle during the absolute refractory period. In this phase, the electrical signals activate the mobilization of calcium ions in the cardiomyocytes. The mechanism of action of the CCM can be summarizing as follows: CCM signals applied during the absolute refractory period cause an increase of cytosolic calcium during the systole, resulting in improving the cardiac contraction [12]. The mechanism of action explains the typical ECG of a patient with CCM and the nurses must be able to recognize it in order not urgently alert the doctor. This is the reason why nurses as well should know it. Furthermore, nurses have to be aware about the effects of such therapy. A few seconds after the delivery of the therapy, normalization of the activity of the proteins that are involved in regulation of intracellular calcium, occurs. After a few hours, there is a progressive normalization of the abnormal expression of fetal gene program, which is a characteristic of heart failure. Reverse remodeling has been demonstrated within 3 months, with reduction of mechanical and neuro-hormonal stress and increase of left ventricular ejection fraction. CCM restores the structure and function of damaged cells to their normal state [13]. Due to this action, CCM improves clinical outcomes in terms of exercise tolerance and QOL at 6 months [14], and this is the reason why guidelines published in 2016 and the Consensus HFA ESC 2019, state that CCM can be considering in selected patients with HF [15]. In 2020, Giallauria et al. evaluated the three currently available randomized controlled trials of CCM therapy for treatment for patients with heart failure. This comprehensive meta-analysis made the authors conclude that CCM provides statistically significant and clinically meaningful benefits in measures of functional capacity and HF-related quality of life [16]. The latest ESC guidelines on heart failure (2021) suspend the judgment on CCM ('under evaluation'), since its effect on the long-term mortality rates of patients with heart failure has not evaluated yet in a randomized controlled multicenter trial [17]. However, it is noteworthy that some preliminary studies showed that CCM improves clinical outcome in terms of exercise tolerance and QOL. Besides, it improves long-term survival, compared with the mortality predicted by the Sattle Heart Failure Model Score and reduces hospitalizations by 75%. [18]. Due to these considerations, we highlighted that the cardiology nurses have not an adequate preparation. Because of this, patient care inevitably suffers. This is the reason why we believe that it is mandatory for the nurse to be updated both about procedures and about devices. They should have adequate knowledge about the indications and the mechanism of action of devices. Furthermore, as regard the CCM, it is mandatory for the cardiology nurses, the knowledge of the typical ECG of a patient implanted with such device.

Acknowledgement

The authors warmly thank Serena Costanza Uran for her collaboration in the translation

Funding statement

This paper did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

There are no competing interests for this study.

Authors’ contribution

Dr. C. Uran: Investigation, conceptualization, resources, preparation and translation of the paper. Dr. M Falco; P. Piscitelli; Dr. G. Bombace; Dr. P. Eterno: Preparation

References

- https://www.fda.gov/media/123038/download;

- Abraham WT, Smith SA. Devices in the management of advanced, chronic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(2):98-110.

- Abraham W.T et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Cardiac Contractility Modulation. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2018;

- Kim Rajappan, Cardiac Department, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headley Way, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK; Education in Heart Arrhythmias. Permanent pacemaker implantation technique: part I; http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2007.132753

- Rajappan K. Permanent pacemaker implantation technique: part II. Heart. 2009;95(4):334-342. doi:10.1136/hrt.2008.156372

- Porfili A. Protocollo infermieristico per procedure di elettrostimolazione: impianto o sostituzione di Pacemker, Defibrillatori, Dispositivi per la terapia di re sincronizzazione cardiaca (CTR) Linee guida AIAC 10.2018

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(35):3427-3520. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364

- Nahla Shaaban Ali; Warda Youssef; Abdo Mohamed; Ali Hussein Nurses' knowledge and practice regarding implantable cardiac devices in Egypt. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing 10, No. 1. Published Online:26 Dec 2014https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2015.10.1.34

- Steffes SS, Thompson EA, Bridges EM, Dougherty CM. Knowledge of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Purpose and Function Among Nurses in the United States. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32(3):304-310. doi:10.1097/JCN.0000000000000339

- Tagney J. Can nurses in cardiology areas prepare patients for implantable cardioverter defibrillator implant and life at home? Nurs Crit Care. 2004;9(3):104Y114

- Donna Fitzsimons, Matthew A Carson, Tina B Hansen, Lis Neubeck, Mu’ath I Tanash, Loreena Hill, The varied role, scope of practice, and education of cardiovascular nurses in ESC-affiliated countries: an ACNAP survey, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Volume 20, Issue 6, August 2021, Pages 572–579, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvab027

- Borggrefe, M.; D. Burkhoff (Jul 2012). “Clinical effects of cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) as a treatment for chronic heart failure”. Eur J Heart Fail. 14 (7): 703–712.

- Butter, C.; et al. (May 2008). “Cardiac Contractility Modulation Electrical Signals Improve Myocardial Gene Expression in Patients With Heart Failure” (PDF). J Am Coll Cardiol. 51 (18):1784–1789.

- Kuschyk et al. Cardiac Contractility Modulation treatment in patients with symptomatic heart failure despite optimal medical therapy and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) International Journal of Cardiology 277 (2019) 173-177 .

- Petar M. Seferovic et al ”Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of The Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology.

- Giallauria F, Cuomo G, Parlato A, Raval NY, Kuschyk J, Stewart Coats AJ. A comprehensive individual patient data meta-analysis of the effects of cardiac contractility modulation on functional capacity and heart failure-related quality of life. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(5):2922-2932.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2021 Oct 14;:]. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599-3726.

- “MAGGIC” Heart Failure Risc Calculator according to Pocock et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39372 patients from 30 studies, Eur Heart J (2013) 34(19) 1404-1413.

Figure 1. The Minnesota questionnarie 21 items

Figure 2. ECG of a patient with a CRT-D system, implanted with the CCM device

Table of abbreviations

Sleep Quality Related to Vigilance Among Nurses in Hospital: A Cross Sectional Study

Debbie Nomiko1*, Ernawati1, Bettywaty Eliezer1

1Nursing Department, Health Polytechnic Ministry of Health Jambi, Indonesia

Corresponding author: Debbie Nomiko, dr. Tazar Street, BuluranKenali, Kec. Telanaipura, Kota Jambi, Jambi 36361, Indonesia, Orcid :https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3623-7937, Phone: +62 812-7897-981, Email: debbiedebbienomiko@gmail.com

Cita questo articolo

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Sleep quality disorders may cause a decrease in concentration and work performance of individual. It is also believed that nurses with work shifts as health workers may run into sleep quality disorders. Several researches have shown the relationship between sleep quality and the work performance of nurses in shifts duty. This study aimed to determine the relationship of sleep quality and vigilance of nurses in shifts duty in Raden Mattaher hospital Jambi.

Methods: A cross sectional study was performed recruiting 97 nurses working shifts in 3 inpatients wards of the Raden Mattaher Hospital Jambi. Socio-demographic details and data nurses alertness were collected using ad hoc questionnaires, data sleep quality were collected using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Relationships among sleep patterns and alertness variables were investigated. Data were analyzed by univariate and chi-square test (CI 95%). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 16.0.

Results: Results showed an average of 29.4 years of age. Respondents were mostly female, married with working time <5 years. The results of the bivariate analysis show there was not relationship between sleep quality and vigilance of nurses who undergoing shifts in Raden Mattaher hospital Jambi with p-value 0.35.

Conclusion: There was not a relationship between sleep quality and vigilance among nurses undergoing a shift in patients' rooms

Keywords: Nurses, Sleep Quality, Wakefulness, Shift Work Schedule

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of sleep quality disorders every year tends to increase, one of the causes is fatigue due to excessive work volume [1–4]. Poor sleep quality may cause adverse effects workers physical and psychological health leading to negative consequence workplace such as mistakes and reduced performances [5–8]. Health professionals have been known to experience fatigue at times. The condition has also long been associated with reduced patient safety [9,10]; decreased satisfaction, health and well-being [11–13]; more conflict among team members [14]; risk of needle stick injuries [14,15] and increased staff turnover [10]. Nurses, the largest group of healthcare providers, are prone to relatively high acute burnout, chronic fatigue, and recovery from fatigue after shift changes [16]. It is closely related to the demands they face throughout the working day, such as physical, mental, emotional demands and pressures associated with shift and non-standard work schedules. These factors place hospital nurses very vulnerable to burnout and its accompanying effects [17].

Nurses are professional workers who use a shift work system, so it can be ascertained that sleep quality disorders can also occur in nurses who undergo shifts [18–20]. Shift work has an impact on disturbances in circadian rhythms [21], and the main one being sleep pattern disturbances that cause sleep deprivation and fatigue [22,23].

Vigilance is degree of readiness of a person in responding to something [24] A person's level of vigilance is needed at work. Accidents occur as a result of decreased levels of alertness [25]. Variables that affect the level of alertness are monotonous state, level of sleepiness, psychophysiology, distraction, and work fatigue. In the variable of sleepiness level, there are 3 indicator variables, namely, circadian rhythm, sleep quality, and sleep time [26,27]. Research results show that 78% of nurses who work shifts experience changes in sleep quality. Furthermore, poor sleep quality is one of the contributing factors to medical errors that occur in health services [28–30]. The impact of poor sleep quality has been widely studied. Sleep absence is an important predictive factor influencing the occurrence of various chronic diseases such as hypertension [31] and cardiovascular disease [32], and diabetes [33]. Nurses' inconsistent sleep habits can have a severe impact on their health as well as their ability to do their jobs [34,35].

METHODS

Trial design

A cross-sectional study was made at the Raden Mattaher Hospital Jambi.

Participants

The population in this study was all shift nurses in 3 inpatient installations at Raden Mattaher Hospital Jambi with a total sample of 97 people with the criteria of nurses in the inpatient installation, not leave, having at least a minimum nursing diploma.

Intervention

A study questionnaire was made to collect socio-demographic details and a 24 items questionnaire was implemented to collect nurses’ alertness data. to four point scored Likert scales (always, often, sometimes and never) were used for the self-assessment of nurses’ alertness before, during and after care activities, with particular attention to missed cares, mistakes and documentation management. Nurses’ sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) tool [36]. Authors declare that the PSQI (Indonesian version) permission to use was obtained by the copyright property.

The PSQI is widely considered the gold standard tool for sleep patterns evaluation and quality of sleep assessment. It provides a global score ranged from 0 to 21 where scores higher than 5 means poor sleep quality. Furthermore, it provides 7 sub-scores assessing sleep patterns: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunctions. The PSQI questionnaire was translated into Indonesian and

tested for reliability with Cronbachs alpha result of 0.753. Data were collected by three interviewers who were unknown to the participants before the study.

Blinding

In this study, 3 enumerators were used to collect research data. The previous enumerators did not know the participants because they were students who had been trained by the researcher before collecting data.

Ethical Consideration

Before carrying out data collection, the researcher first took care of ethical permission. The authors state that this study followed all ethical clearance processes and was approved by the health research ethics committee of Jambi Universitys Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Statistical methods

Data were presented as numbers or percentages for categorical variables. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median with Interquartile Range (IQR). The chi square test and Fisher's exact test were performed to evaluate significant differences of proportions or percentages between two groups. Particularly Fisher's exact test was used where the chi square test was not appropriate. All tests with p-value (p)<0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 16.0 application.

RESULTS

Ninety-seven out of one hundred twenty-two nurses working shifts in 3 wards) qualified nurses

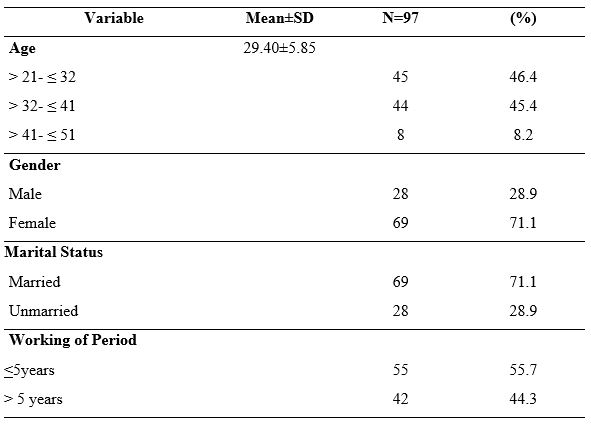

completed their studies. The results of this study presented in the table 1.

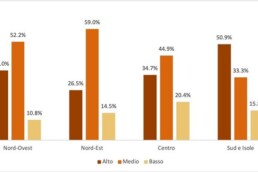

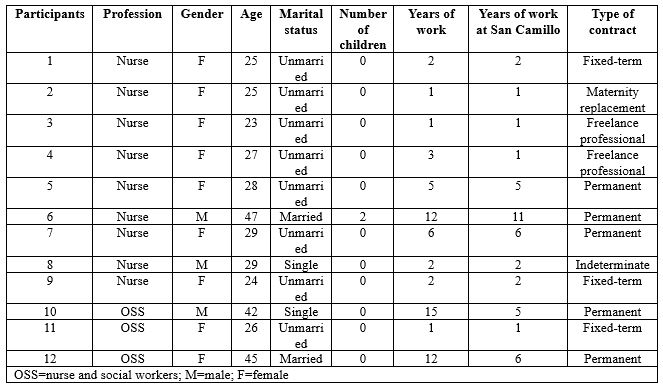

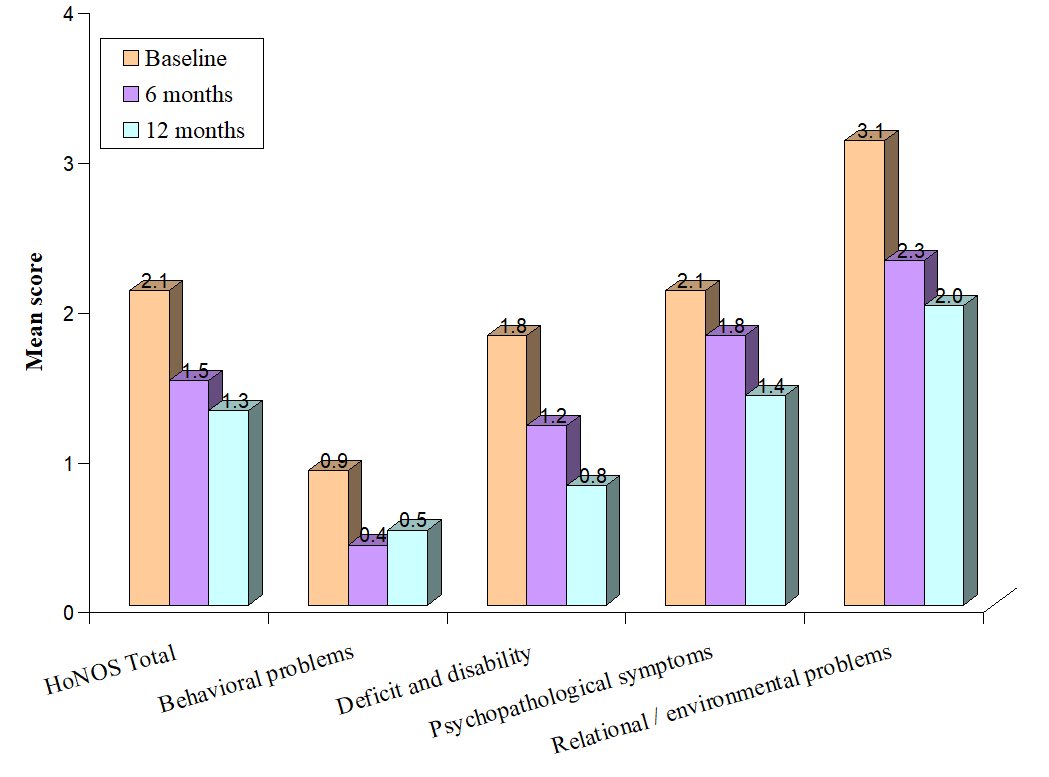

Table 1. Demographic Data of Nurses Undergoing Shift

Most of respondents were female (71.1%), married (71.1%) and have working of period < 5 years (55.7%). These results showed the average age of the respondents was 29.40 years, and the age range was between 21-51 years (SD 5.85).

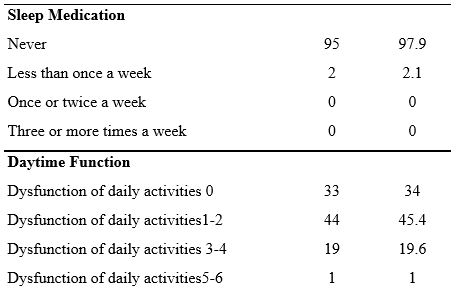

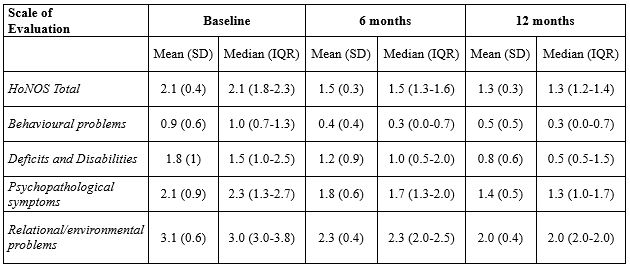

Table 2 shows the results of the assessment of the seven components of the respondent's sleep quality, it was found that the component of the use of sleeping pills (using pills) had the highest score in terms of not using, namely 97.93%, the second highest score was the component of the subject's sleep quality, namely the subjective average of respondents stated 86.6% had good sleep quality. The results also showed that most of the respondents had sleep disturbances as much as 65%, and as many as 40% had sleep efficiency in the range of 75-84%.

That most nurses (86.6%) have good sleep quality based on subjective sleep quality. In the second component (sleep latency), most of the respondents (51.5%) had a sleep latency of 1-2 hours, and merely a small portion (7.2%) had a sleep latency of 5-6 hours.

Table 2. Sleep Quality Components: Subjective and Objective Sleep Quality measures

In the third component (sleep duration), most of the respondents, as many as 32% of respondents, had sleep duration < 5 hours and only five respondents (5.2%) had sleep duration > 7 hours. Furthermore, 26.8% of the fourth component had a daily sleep efficiency > 85%, and only 14 respondents (14.4%) had a daily sleep efficiency of 14.4%. This result is slightly different from the previous study [49], which showed that 73.5% of nurses have sleep efficiency >85%.

Sleep quality in terms of sleep disturbance components shows that most of the respondents (67%) have sleep disorders with a score of 1-9, then for the use of sleeping pills, most of the respondents (97.93%) have never used sleeping pills at all.

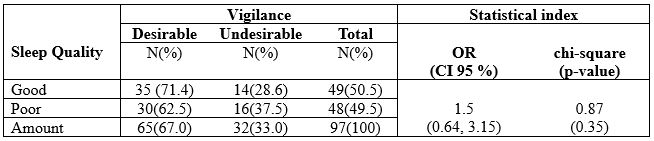

Table 3. The Correlation Between Sleep Quality and Vigilance Among Nurses undergoing Shift

The results of statistical tests obtained a p-value = 0.35, so it can be concluded that there was not a

significant relationship between sleep quality and vigilance among nurses who undergoing a shift in

the hospital.

DISCUSSION

Statistically it was found that in this study, there was no relationship between sleep quality and nurses' work alertness, although descriptively it can be reported that Nurses with good sleep quality tend to have good vigilance, and contrarily, nurses who have poor sleep quality tend to have less vigilance (see table 3). It significantly affects the productivity of nurses at work, where nurses in carrying out their work with good vigilance will work with good performance compared to nurses who are less alert.

Nurses who work night and rotating hours have been proven to have more trouble staying awake on duty and make twice as many mistakes as those who work day and evening shifts. More than 20% of workers in industrialized countries work shifts, and about 10% of them are diagnosed with sleep disorders [37]. Many factors affect sleep quality, one of which is shift work. Individuals who work shifts or shifts have difficulty adjusting to changing sleep schedules [6].

Poor sleep quality mainly occurs in nurses who use shift work systems. A study by Murphy et al., [38] found that shift work was significantly associated with poor sleep quality after controlling for variables of age, gender, and length of work.

This study also found almost the same proportion of respondents between respondents who had good and bad sleep quality, while most of the respondents had the desired of vigilance, which was around 67%. A systematic review study conducted by Dall’Ora et al. [39] found that shift characteristics are related to employee performance, and having sufficient rest time positively affects employee vigilance. Furthermore, Wahyuni [40] found a decrease in vigilance in night shift nurses with a proportion of decreased vigilance of 71.1%. However, statistically, it was not proven

to have a significant effect. The factor that influences the level of alertness before office hours is the

sleep quality. Lack of sleep results in a person's condition is less energetic and not enthusiastic [41].

We report that research data show that nurses predominately have a sleep latency of 1-2 hours, and only a small proportion (7.2%) have a sleep latency of 5-6 hours. Sleep latency is the length of sleep from start to fall asleep [42,43]. One of the factors that can affect sleep latency is bedtime habits that can disrupt a person's sleep and have an impact on increasing sleep latency [44].

This result is in line with the results of a previous study [45] that most respondents (60.3%) shift nurses experienced sleep disturbances less than once a week. Of all the sleep quality components, the sleep disturbance component had the highest mean of 1.44 with a standard deviation of 0.90 in a study of nurses undergoing shifts in Jordan [46].

Nurses’ poor sleep quality leads to a number of negative health outcomes. Nurses suffering from

poor sleep quality were more prone to develop burnout [47], depression and anxiety [48]. In addition, poor sleep could impair cognitive performance, such as concentration and memory, which may lead to poor work performance and even affect patients’ safety [49-51].

Effective measures, such as education on sleep hygiene [48], yoga [52] and cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia [53], should be considered to improve nurses’ sleep quality, quality of life, and patients’ safety.

CONCLUSION

The current study found that sleep quality was not a significant factor contributing to nurses' vigilance and medical error. Nevertheless, we still suggest that hospital managers should apply a 15-30 minute rest period during work shifts for nurses and pay attention to work rotation times, especially night shifts as a strategy to increase vigilance to prevent fatigue, sleepiness, and work errors.

LIMITATION OF STUDY

This study was only conducted in 3 hospital wards, so it cannot be compared with the same conditions in different hospitals. No intervention was carried out in this study to improve nurses' sleep quality and increase alertness while working. Other factors that influence Precautions, such as lighting conditions, environment, pills, caffeine, and other ingredients, were not studied.

Authors’ contribution

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to the director Director of Health Polytechnic, Ministry of Health Jambi, Indonesia for its support for the implementation of this research

Funding

This research received funding from the Development and Empowerment of Human Resources in Public Health (BPPSDMK) Indonesia

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest in this research.

REFERENCES

- Deng X, Liu X, Fang R. Evaluation of the correlation between job stress and sleep quality in community nurses. Medicine. 2020;99(4).

- Boll J. Development of a Measure of Nurse Vigilance from the Patient’s Perspective: A Content Validity Study. 2014;

- Surani S, Hesselbacher S, Guntupalli B, Surani S, Subramanian S. Sleep quality and vigilance differ among inpatient nurses based on the unit setting and shift worked. Journal of patient safety. 2015;11(4):215–20.

- Kaliyaperumal D, Elango Y, Alagesan M, Santhanakrishanan I. Effects of sleep deprivation on the cognitive performance of nurses working in shift. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 2017;11(8):CC01.

- Sayilan AA, Kulakaç N, Uzun S. Burnout levels and sleep quality of COVID-19 heroes. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2020;57(3):1231–6.

- PA Potter AP. Fundamental Keperawatan. Jakarta: EGC; 2006.

- Tsai J-C, Chou K-R, Tsai H-T, Yen Y-C, Niu S-F. Effects of nocturnal sleep quality on diurnal cortisol profiles and attention in nurses: A cross-sectional study. Biological Research for Nursing. 2019;21(5):510–8.

- Di Muzio M, Diella G, Di Simone E, Pazzaglia M, Alfonsi V, Novelli L, et al. Comparison of Sleep and Attention Metrics Among Nurses Working Shifts on a Forward-vs Backward-Rotating Schedule. JAMA network open. 2021;4(10):e2129906–e2129906.

- Rainbow JG, Drake DA, Steege LM. Nurse health, work environment, presenteeism and patient safety. Western journal of nursing research. 2020;42(5):332–9.

- Smith-Miller CA, Shaw-Kokot J, Curro B, Jones CB. An integrative review. The journal of nursing administration. 2014;44(9):487–94.

- Asakura K, Asakura T, Satoh M, Watanabe I, Hara Y. Health indicators as moderators of occupational commitment and nurses’ intention to leave. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 2020;17(1):e12277.

- Austin S, Fernet C, Trépanier S, Lavoie‐Tremblay M. Fatigue in new registered nurses: A 12‐month cross‐lagged analysis of its association with work motivation, engagement, sickness absence and turnover intention. Journal of nursing management. 2020;28(3):606–14.

- Bazazan A, Dianat I, Rastgoo L, Zandi H. Relationships between dimensions of fatigue and psychological distress among public hospital nurses. Health promotion perspectives. 2018;8(3):195.

- Han K, Trinkoff AM, Geiger-Brown J. Factors associated with work-related fatigue and recovery in hospital nurses working 12-hour shifts. Workplace health & safety. 2014;62(10):409–14.

- Fisman DN, Harris AD, Rubin M, Sorock GS, Mittleman MA. Fatigue increases the risk of injury from sharp devices in medical trainees results from a case-crossover study. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28(1):10–7.

- Barker LM, Nussbaum MA. Fatigue, performance and the work environment: a survey of registered nurses. Journal of advanced nursing. 2011;67(6):1370–82.

- Steege LM, Drake DA, Olivas M, Mazza G. Evaluation of physically and mentally fatiguing tasks and sources of fatigue as reported by registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2015;23(2):179–89.

- Reinke L, Özbay Y, Dieperink W, Tulleken JE. The effect of chronotype on sleepiness, fatigue, and psychomotor vigilance of ICU nurses during the night shift. Intensive care medicine. 2015;41(4):657–66.

- Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell RB, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiology international. 2012;29(2):211–9.

- Ruggiero JS, Redeker NS, Fiedler N, Avi-Itzhak T, Fischetti N. Sleep and psychomotor vigilance in female shiftworkers. Biological research for nursing. 2012;14(3):225–35.

- Sun Q, Ji X, Zhou W, Liu J. Sleep problems in shift nurses: A brief review and recommendations at both individual and institutional levels. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019;27(1):10–8.

- Maurits LS, Widodo ID. Faktor dan Penjadualan Shift Kerja. Teknoin. 2008;13(2):18–22.

- Dong H, Zhang Q, Sun Z, Sang F, Xu Y. Sleep disturbances among Chinese clinical nurses in general hospitals and its influencing factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–9.

- Dorrian, J., Roach, Gregory.D., Fletcher, A., Dawson D. Simulated train driving: Fatigue, self awareness and cognitive disengagement. Applied Ergonomics. 2007;

- Desai A V., Haque MA. Vigilance monitoring for operator safety: A simulation study on highway driving. Journal of Safety Research. 2006;37(2):139–47.

- Zeng L-N, Yang Y, Wang C, Li X-H, Xiang Y-F, Hall BJ, et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in nursing staff: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2020;18(6):746–59.

- Tu Z, He J, Zhou N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2020;99(26).

- Arimura M, Imai M, Okawa M. Sleep, Mental Health and Errors in Nurses. Industrial health. 2010;48(6):811–7.

- Balas MC, Casey CM, Scott LD, Rogers AE. Maintain vigilance in the ICU. Nursing2020 Critical Care. 2007;2(4):38–44.

- Boughattas W, El Maalel O, Chikh R Ben, Maoua M, Houda K, Braham A, et al. Hospital night shift and its effects on the quality of sleep, the quality of life, and vigilance troubles among nurses. International Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2014;2014.

- Wang Y, Mei H, Jiang Y-R, Sun W-Q, Song Y-J, Liu S-J, et al. Relationship between duration of sleep and hypertension in adults: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2015;11(9):1047–56.

- Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European heart journal. 2011;32(12):1484–92.

- Alimoradi Z, Lin C-Y, Broström A, Bülow PH, Bajalan Z, Griffiths MD, et al. Internet addiction and sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 2019;47:51–61.

- Gómez-García T, Ruzafa-Martínez M, Fuentelsaz-Gallego C, Madrid JA, Rol MA, Martínez-Madrid MJ, et al. Nurses’ sleep quality, work environment and quality of care in the Spanish National Health System: observational study among different shifts. BMJ open. 2016;6(8):e012073.

- Kang J, Noh W, Lee Y. Sleep quality among shift-work nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied nursing research. 2020;52:151227.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989;28(2):193–213.

- Basent B. Shift-work sleep disorder. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(5):519–21.

- Murphy R, Osterweil D, MscED CMD, Spivack BS, Zee PC. Improving Sleep Management in the Elderly. Citeseer; 2010.

- Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: A literature review. International journal of nursing studies. 2016;57:12–27.

- Wahyuni I, Dirdjo MM. Hubungan Kelebihan Waktu Kerja dengan Kelelahan Kerja dan Kinerja pada Perawat di Ruang Perawatan Intensif RSUD Abdul Wahab Sjahranie Samarinda. Borneo Student Research (BSR). 2020;1(3):1715–24.

- Budiawan W, Prastawa H, Kusumaningsari A, Sari DN. Pengaruh Monoton, Kualitas Tidur, Psikofisiologi, Distraksi, Dan Kelelahan Kerja Terhadap Tingkat Kewaspadaan. J@Ti Undip : Jurnal Teknik Industri. 2016;11(1).

- Rocha MCP da, Martino MMF De. Stress and sleep quality of nurses working different hospital shifts. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2010;44:280–6.

- Fietze I, Knoop K, Glos M, Holzhausen M, Peter JG, Penzel T. Effect of the first night shift period on sleep in young nurse students. European journal of applied physiology. 2009;107(6):707–14.

- Mubarok. Buku Ajar Kebutuhan Dasar Manusia : Teori & Aplikasi dalam Praktik. Jakarta: EGC; 2007.

- Safitrie A, Ardani MH. Studi Komparatif Kualitas Tidur Perawat Shift dan Non Shift di Unit Rawat Inap dan Unit Rawat Jalan. Prosiding Konferensi Nasional PPNI Jawa Tengah. 2013;17–23.

- Suleiman K, Al-Khaleeb T, Al-Kaladeh M, Sharour LA. The Effect of Shift Fluctuations on Sleep Quality among Nurses Working in the Emergency Room in Amman, Jordan. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Health. 2020;10(1):11–7.

- Giorgi, F., Mattei, A., Notarnicola, I., Petrucci, C., & Lancia, L. Can sleep quality and burnout affect the job performance of shift-work nurses? A hospital cross-sectional study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2018; 74, 698–708. doi:10.1111/jan.13484

- Baroni, A., Bruzzese, J. M., Di Bartolo, C. A., Ciarleglio, A., & Shatkin, J. P. Impact of a sleep course on sleep, mood and anxiety symptoms in college students: A pilot study. Journal of American College Health, 2018; 66, 41–50. doi:10.1080/07448481.2017.1369091

- Barbe, T., Kimble, L. P., & Rubenstein, C. Subjective cognitive complaints, psychosocial factors and nursing work function in nurses providing direct patient care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2018; 74, 914–925. doi:10.1111/ jan.13505

- Caruso, C. C. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabilitation Nursing, 2014; 39, 16–25. doi:10.1002/rnj.107

- Park, E., Lee, H. Y., & Park, C. S. Association between sleep quality and nurse productivity among Korean clinical nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2018; doi:10.1111/jonm.12634

- Fang, R., & Li, X. A regular yoga intervention for staff nurse sleep quality and work stress: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2015; 24, 3374–3379. doi:10.1111/jocn.12983

- Kalmbach, D. A., Cheng, P., Arnedt, J. T., Anderson, J. R., Roth, T., Fellman-Couture, C., … Drake, C. L. Treating insomnia improves depression, maladaptive thinking, and hyperarousal in postmenopausal women: Comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. Sleep Medicine, 2019; 55, 124–134. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.11.019

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

DEVELOPMENT AND EFFECTIVENESS OF AUGMENTED REALITY-BASED LEARNING FOR HEALTH SCIENCE STUDENTS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Lia Artika Sari1, Muhammad Rusdi2, Asrial2, Herlambang2

1 Doctorate student in Education MIPA Jambi University, Indonesia

2 Jambi University, Indonesia

Corresponding author: Lia Artika Sari Jl. Prof DR GA Siwabessy No.42, Buluran Kenali, Kec. Telanaipura, Kota Jambi, Jambi 36122, Indonesia, Tel: +6282196687959, Email: liaartikasari57@gmail.com, Orcid : https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5285-5356

Cita questo articolo

ABSTRACT

Background and Objective. The rapid development of technology makes it easier for teachers to continue to be interactively connected with students, for example, by using Augmented Reality technology. We conducted this review intending to investigate the diffusion and the effectiveness of AR technology as a learning media for students from various health fields.

Materials and Method. This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols) Checklist. We used some databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, Wiley Online Library, and Sciencedirect to search relevant literature with eligibility criteria, namely articles published in the period 201-2021, and discuss the development of Augmented Reality -based applications for learning students in the field of health

Results. The studies included are on the development of AR-based learning applications carried out to improve the clinical skills of health students (Medicine, Nursing, and Midwifery). Various types of application development are carried out including anatomy, Endotracheal Intubation, AR Prototype for Medical Surgery, Intravascular Neurosurgery, injection skills, and Laparoscopic.

Conclusion. The use of Augmented Reality as a learning medium really helps improve the understanding and skills of students majoring in health sciences.

Keywords: Development, Augmented Reality, Health-Science, Students

INTRODUCTION

The use of technology in the education of health science students has evolved over the years. These trends are mainly evolving in response to the challenges facing health education [1]. The use of simulation in health education has been applied in the last 50 years [2]. Augmented reality technology is an example of virtual reality technology developing rapidly in nursing education [3].

Augmented Reality (AR) technology refers to virtual elements to display the actual physical environment to create mixed-reality files in real-time. It complements and enhances the perceptions that humans acquire through their senses in the real world [4]. AR provides various levels of understanding and interaction, which can help students in e-learning activities [5]. For example, in an AR learning environment, motivational factors related to attention and learning satisfaction are rated higher than slide-based learning [6]. Today's development of smartphone technology makes AR technology more accessible to students and lecturers; for example, mobile learning (m-learning) using AR has become a trend [7].

Simulations using AR technology can replicate real-world aspects so that a safe learning environment is available for students where they can practice until the expected skill competencies are achieved [8]. Simulation has become an integral part of nursing curricula [9], which involves using patient simulators, trained people, real-life virtual environments, and role play [10].

Technological advances over time have increased the realism and authenticity of the simulated environment, leading to increased reactions, satisfaction, learning attitudes, cognitive and affective outcomes among health students in general [11].

Clinical health services have also used AR because it provides an internal picture of the patient, without the need for invasive procedures [12–15]. Medical students and professionals need more situational experience in clinical care, especially for patient safety, so this shows that there is a real need to continue developing the use of AR in health education.

The focus of studies on AR in recent years [16,17] has highlighted the belief that AR provides medical students with rich contextual learning to help achieve core competencies, such as decision making, work for effective teams, and creative adaptation of global resources to address local priorities [18], AR provides more authentic and engaging learning opportunities for various learning styles, providing students with a more personalized and exploratory learning experience [19]. The security of the patient will also be awake if an error occurs during skills training with AR [20].

Objective

This review was conducted to describe the development of AR technology as a learning medium for students from various health fields. This study is expected to be a reference material for teachers in learning strategies.

METHOD

Review Protocol

The research design is a Systematic Review, using the PRISMA-P 2009 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols) Checklist.

Searching strategy

To search for literature using the PubMed database, Google Scholar, Wiley Online Library, and Sciencedirect using the keywords "Developing" AND "Augmented Reality" AND "Clinical practice" AND (Medical OR Nurse OR Midewifery) "College student".

We categorize the search into five categories that are considered to represent the topic of Augmented Reality development, namely AR typology, AR features and advantages, AR user perceptions, AR effectiveness in supporting learning, and AR design. Each category was analyzed to identify the best lessons, experiences, and evidence related to the design and development of AR.

Eligibility Criteria

The articles included in this review use the development method, with the subject of the trial being health students. In addition, the articles used are in English and full text, published in the period 2010–2020. Furthermore, the data obtained are then analyzed using quantitative descriptive methods and a narrative is produced that explains the study results.

The study results were documented to identify the effectiveness of using augmented reality in student health learning.

Study Type

The studies included in the criteria for this review are only limited to studies on the development

of Augmented Reality technology for student learning in the health sector. Articles entered are in English, full text, and is not a thesis or dissertation.

Type of Participant/Population Target

The participants used were health students (Medicine, Nursing, Midwifery) who did clinical practicum (Clinical Skill). There are no restrictions on age, gender, level/semester, as long as participants do clinical practicum learning (clinical skills).

Article Quality

Quality assessment was carried out on six journals that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist criteria. Journals are good if they meet at least 80%, moderate if they meet 50–80% and weak if they meet less than 50% of the criteria. Articles are used in good to moderate categories for further data synthesis, namely, grouping similar extracted data according to the results to be measured to conclude.

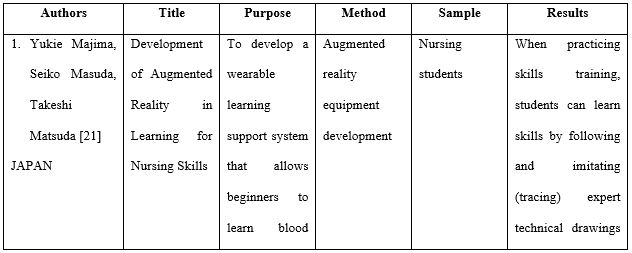

RESULTS

Literature Identification and Selection

There were 319 articles identified from four databases (Pubmed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and Wiley Online Library) relevant to the review topic, where the assessment or screening was based on the title and abstract of the articles obtained. 66 studies were removed because they were duplicate. After screening the title and abstract, 219 studies were removed due to irrelevant theme, not AR topic, and proceeding types. At the eligibility stage, 28 studies were not fit the inclusion criterias.

Critical Appraisal

Based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist, six pieces of literature are in the excellent category, and two pieces of literature are in the weak category.

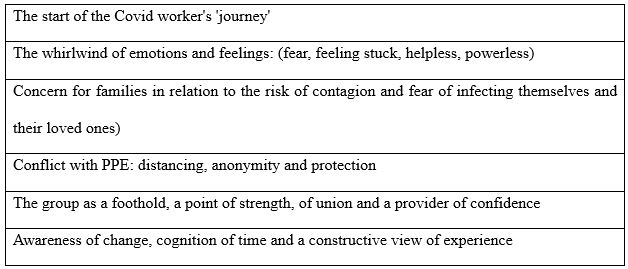

To maintain the quality of the literature studies made, this review only uses six good-quality journals, and then data extraction will be carried out (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart: Strategy for Searching for Development of Augmented Reality in Educational Situations for Health-Science Students

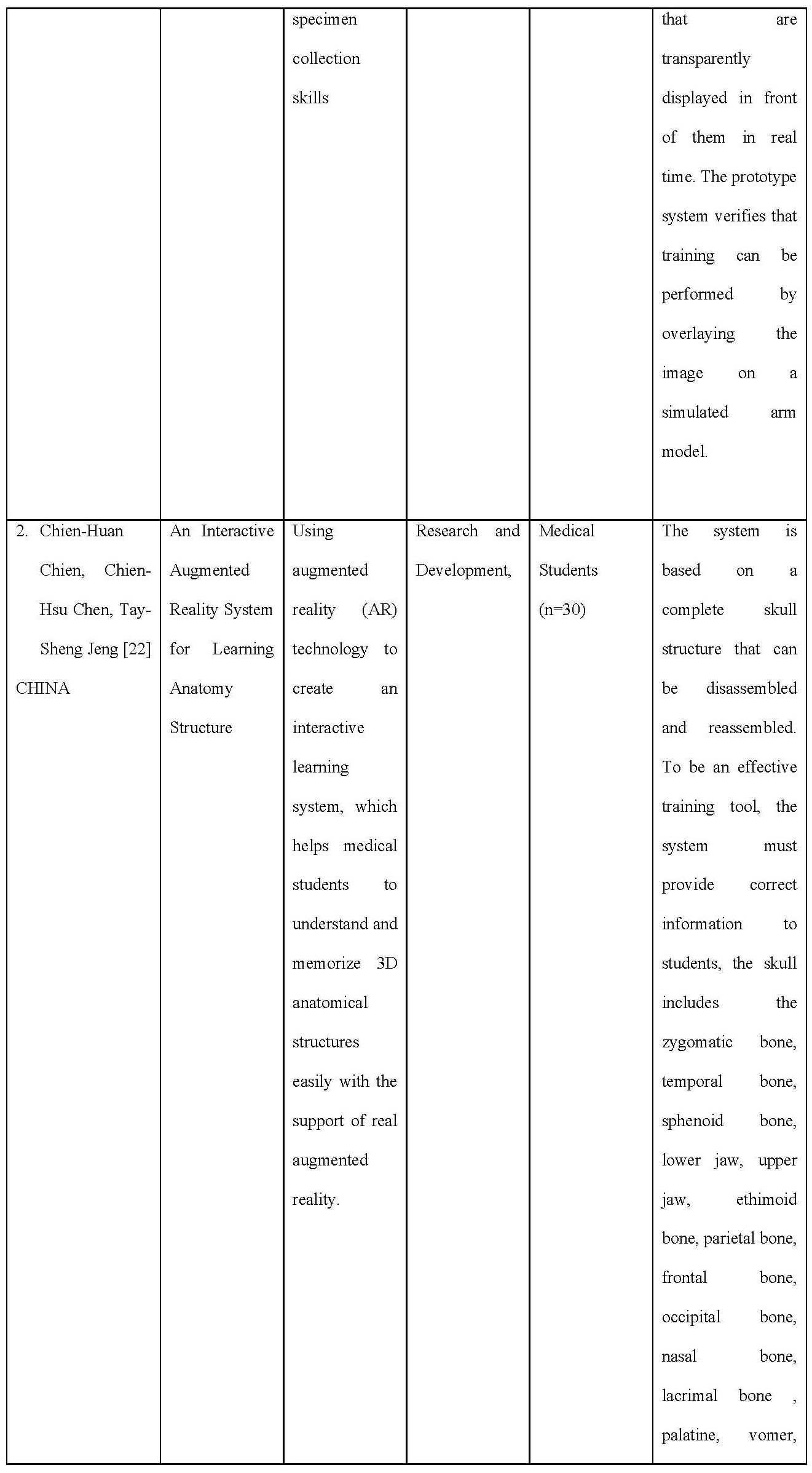

After bearing the assessment, screening, and feasibility, the authors agreed to include six studies in this systematic review of the literature. Furthermore, the extraction of data from each of the included literature we describe in the following table displays the critical information needed with the theme of the study.

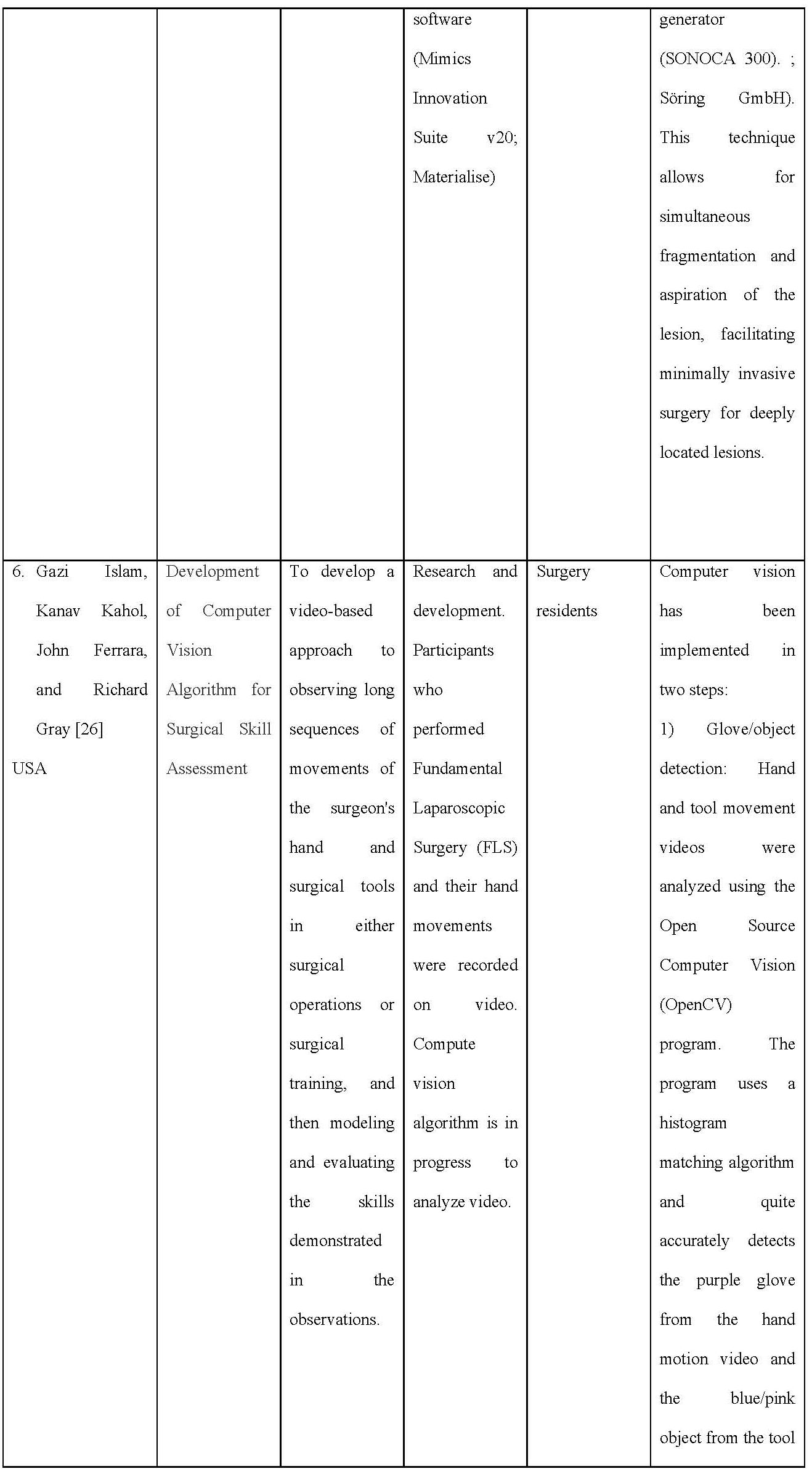

Table 1. Data Extraction on Included Articles

Characteristics of the studies included

The articles included in the inclusion criteria were six from several countries, including the USA as many as two articles, Canada 1 article, Sweden 1 article, Ireland 1 article, and Japan 1 article. Overall, the article taken is a study on the development of AR-based learning applications carried out to improve the clinical skills of health students (Medicine, Nursing, and Midwifery). Various types of application development are carried out including anatomy, Endotracheal Intubation, AR Prototype for Medical Surgery, Intravascular Neurosurgery, injection skills, and Laparoscopic.

Critical Appraisal

Based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist, six pieces of literature are in the excellent category, and two pieces of literature are in the weak category. To maintain the quality of the literature studies made, this review only uses six good-quality journals, and then data extraction will be carried out.

Table 2. Summary of Critical appraisal based on JBI checklist

AR system design

In Majimas’ work, the learners can learn experts’ nursing skills without moving their lines of sight. When practicing skills training, learners can learn skills by following and imitating (tracing) the images of experts’ techniques that are dis-played transparently in front of them in real time. The prototype system verified that training is possible by overlaying images on a simulation arm model.

Chien and colleague The system is based on a complete structure of the skull which can be decomposed and reassembled. To be an effective training tool, the system has to provide correct information to the students, the skull includes zygomatic bone, temporal bone, sphenoid bone, mandible, maxilla, ethimoid bone, parietal bone, frontal bone, occipital bone, nasal bone, lacrimal bone, palatine, vomer, and inferior nasal concha.

Torregrosa and team developed an ARBOOK which includes a standard part of descriptive anatomy of the lower limb including osteology, arthrology, myology, nerve and vascular supply. Each part of the book includes bi-dimensional images and text about the muscles: origin insertion, vascular and nerve supply or action. It also includes a card for each anatomical figure that can be recognized by a digital webcam connected to a computer. The users can modify the actual position of the virtual structure by moving the card. To develop the ARBOOK, more than 100 TC images were needed and the images were processed by OsiriX software and 3D constructed. LabHuman and VMV3D companies performed the animation.

Drapkin study, an open-source T1 and T2 weighted simulated MRI dataset of a normal human brain constructed from a composite of 27 volumetric datasets of the same living subject was obtained from the BrainWeb simulated brain database. This dataset was viewed using GEHC MicroView software, version 2.1.2 (General Electric Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). 3D models were constructed using MicroView to create isosurfaces based on gray scale values within a given region of interest to create a 3D mesh approximating the shape of a given internal brain structure. These computer graphic object composites were exported as a VTK PolyData file and edited using Maya software, version 2010 (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA) and were examined by two neuroanatomists and one neurologist for accuracy and compared to the Netter’s Atlas of Human Neuroscience. The final edited versions were imported back into MicroView 2.1.2 as Wavefront OBJ files and overlaid on top of the original MRI dataset. The final product was a set of digital 3D models of internal brain structures that can be freely rotated and zoomed by the user. To fabricate the 3D-printed models in Licci study, anonymized CT data set of a patient with enlarged CSF spaces was first downloaded from the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) and further processed with the medical segmentation software Materialise Mimics (Mimics Innovation Suite v20; Materialise). The DICOM CT data set consisted of native cross-sectional slices of bone and soft-tissue windows to display the relevant anatomical features. Further processing and segmentation of several anatomical structures according to tissue density (Hounsfield units) was worked out. The virtual cranial vault was designed with the help of the modeling software Materialise 3-Matics to be removable and equipped with realistic, neurosurgical burr holes for endoscopic access. The osseous skull was printed completely (2 parts) with a consumer Replicator+ 3D printer (MakerBot Industries) from polylactic acid (PLA; light gray), and the corresponding ventricle spaces were divided into 2 parts with a wall thickness of 3 mm in transparent PLA material. After printing a total of 5 skull models, the support structures were manually removed, and the two halves of the ventricular system were glued together. These were inserted into the skull model, and the cavity between the ventricular system and the bony skull was filled with 2-component silicone for stabilization.

In the Islam study, they proposed a novel video-based approach for observing continuous, long sequence of surgeon’s hand and surgical tool movements in both surgical operation or surgical training, and then modeling and evaluating the skill demonstrated in the observation. Hand movement of entire surgical procedure is captured using inexpensive video camera. Video data of the tool movement can also be obtained for minimal invasive surgery (MIS). Both of the video data are analyzed using computer vision algorithm and then integrated to correlate with user’s skill level.

For modeling the surgical skill, a stochastic approach is proposed that uses simple arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the processed data. Using this technique, observer-independent models can be developed through objective and quantitative measurement of surgical skills. Because of the non-contact nature of the tracking technique, the system is free from sterile issue and there is minimal interference with the skill execution, unlike other methods that employ instrumented gloves or sensor-based surgical tools.

AR for Nursing skills

There is one study that developed the teaching skills of nurses using AR technology. The skill learned in the study was performing intravenous injections [21].

AR for Anatomy learning

Three studies [22] developed learning methods based on AR technology. AR technology was used to create an interactive learning environment, which allows students to understand the 3D skull structure with visual support [14]. One of the studies gave their app the name ARBOOK, which can be presented in both, printed or electronic version. ARBOOK includes a standard part of descriptive anatomy of the lower limb including osteology, arthrology, myology, nerve and vascular supply [15]. Another study developed 3D Neuroanatomy Teaching Tool. The models were created of the ventricular system, thalamus, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, hippocam-pus, amygdala, fornix, caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, brainstem, cerebral peduncles, and cerebellar peduncles [16].

AR for Surgical training

There are two studies that develop training based on AR technology. The first study involved a neuroendoscopic ventricular lesion removal training [17], and the second study provided two laparoscopic graspers and performed the pegboard transfer exercise on the FLS [18].

DISCUSSION

It is undeniable that the advancement of Augmented Reality technology has had a significant impact on the health sciences. Professions requiring high precision and good psychomotor abilities certainly require more time to practice carrying out their actions. The presence of Augmented Reality technology in its various forms is proven to increase students' abilities and interests in dealing with the learning process.

Under certain conditions, especially during pandemic times where large-scale restrictions are imposed, direct meetings to carry out laboratory practicums are deemed possible, so there must be changes in strategies or effective learning methods for students in dealing with curriculum demands related to learning outcomes. A total of 6 eligible articles have been extracted to provide an overview of the development of Augmented Reality technology-based tools/tools in many health science fields, including Medicine, Nursing,/Midwifery. From the article, the discussion will be described based on the field of development, software and hardware used,

Development area

Anatomy Learning

Two articles develop applications for learning body anatomy based on Augmented Reality [18]. Tried to develop a 3D interactive learning environment of bone structure with visual support. This application is equipped with pop up labels and interactive displays in 3D to make it easier for users to see the position of each bone at various angles. In addition, users are also facilitated with the help of each label with information about the bone so that students no longer need to open books to look for information about the designated bone. To use this 3D application, students/users need hardware devices such as laptops/PCs equipped with cameras and pointers. For testing this device, Chien and colleagues used 30 medical students who had never taken anatomy courses to hope that the participants' responses to this application would be of better quality. At the evaluation stage, participants revealed that the developed application was fascinating because it could provide a complete picture of the displayed bone structure and explain each pop-up label, making it easier to understand and memorize. In addition, another exciting thing is that the reassembled function in the application allows students to see the inner structure of the bone.

Another application developed by Torregrosa and colleagues in 2014 called ARBOOK (Augmented Reality Book) focuses on the anatomical structure of the lower extremities. For its development, 100 TC photos/images are needed, then the images are processed using OsiriX software and 3D object creation. For validation, the questionnaire compiled for the ARBOOK evaluation consists of the categories of task motivation and attention, autonomous work, comprehensive spatial orientation, and 3D interpretation. . Next, an expert assessment will be carried out. Application testing involves first-year health students who have never taken an anatomy course. The test results show a significant difference between learning using ARBOOK and conventional learning. As has been stated in previous studies that the use of virtual materials in anatomy learning can provide good benefits for student learning achievement, especially regarding motivation and independence [27,28].

Augmented Reality technology was also developed in Neuroanatomy learning for MRI exercises developed by Drapkin and colleagues in 2015. The developed application makes the brain image display into a 3D shape. This 3D model begins by using MicroView to form a primary image in the form of isosurfaces and then form a 3D model similar to the shape of the actual brain. The graph is then exported in VTK PolyData file format and edited using Maya software. The editing results are then given to neuroanatomists and neuroscientists to assess the accuracy of the image shape and compared with images on the ATLAS neuroscience Netter. The final image is then placed on top of the actual brain image from the MRI. Next, we entered the pilot phase, which was conducted on participants who were medical students at level 1. The trials showed that this 3D neuroanatomy teaching tool effectively trains medical students to read brain MRI and effectively teach students to identify internal brain structures.

Surgery training

In contrast to learning the body's anatomical structure, surgical skills in surgery require hand-eye coordination, which can be achieved with continuous practice [29]. In surgery, one is not enough to see what other people are doing when performing surgery; that is, to become skilled, it is necessary to "watch and do" [30].

One of the six articles included in this review is an Augmented Reality-based simulation development study for Neuroendoscopic Ventricular Removal exercises [25]. In this development study, a 3D-printed model of synthetic body tissue was created. The idea is based on the limited material for practical surgery such as tumour removal. By using this 3D-printed model, it is hoped that it can accommodate all residents to do exercises repeatedly because this model is reusable.

Overall, the surveyed participants agreed or strongly agreed (Likert scores of 4 and 5) on the realistic nature of the anatomical model of the skull and ventricular system, the technical suitability of the model, the camera view, which was similar to the actual surgical view. Participants also agreed or strongly agreed that the content validity of the simulator is a valuable tool for enhancing surgical competence for neuro-endoscopic procedures that helps develop coordinating skills and represent an excellent practical exercise tool for ventricular tumour removal.

Other Augmented Reality-based surgical simulations are also included in this study. The development study conducted by Islam et al. [26] aims to create a video-based approach to observing surgeon hands and surgical instrument movements in surgery and surgical training. The data is captured with a video camera and then explored using a computer vision algorithm. Furthermore, by analyzing the basic statistical parameters, observer-independent performs objective and quantitative measurements of the surgical skills of the trainees. Computer vision is done through two steps, namely Glove/object detection and motion capture. This application is very suitable for remote assessment of student skills. Between the rater and the assessed, it is possible not to be in the room together; this allows the assessed participants to be calmer in the face of the assessment. Students can also receive virtual and interactive demonstrations of surgical procedures with surgeons carrying out the surgery so that students can experience real situations in the operating room.

Nursing skills

Majima, et all [21] developed a practicum learning system for nursing students based on Augmented Reality, especially in the act of taking blood specimens. In certain types of blood vessels, beginners find it difficult to insert the needle. It is the basis for this research. Through this development, beginners can learn the "art" in the veins and imitate the images displayed in front of them. In injection skills education, both instructors and students are usually very interested in holding a syringe. However, in reality, the teaching given is limited to fixation, and the left finger technique is taught, which is tailored to the characteristics of each patient's blood vessels that are difficult to insert a needle. How to repair and lengthen unstable blood vessels has not been entirely taught.

When practising skills training, students can learn skills by following and imitating (tracing) expert technical drawings transparently displayed in front of them in real-time. The prototype system verifies that training can be performed by overlaying the image on a simulated arm model.

CONCLUSION

The use of Augmented Reality as a learning medium really helps improve the understanding and skills of students majoring in health sciences. The many choices of models in application development provide opportunities for researchers to continue to innovate. Augmented Reality-based learning applications in the future become an absolute thing along with the increasing development of technology.

Limitation

Many databases not used in this review, such as Scopus, Ebsco, IEEE, and others, are very

credible for searching literature/articles. It is due to limited access to these databases. The use of gray literature such as google scholar conducted carefully with agreement of all authors.

The author also has limitations in understanding the software and programming languages used in the articles reviewed, so the authors cannot further discuss the application development process in the six articles reviewed.

Recommendation

This study provides a broad overview of the Augmented Reality-based application development process so that it can be a reference material for future teachers or researchers to be able to innovate in the development of Augmented Reality-based learning applications, for example, in the process of guiding final project students, or multiplying nursing action tutorials that are currently available. Not yet fully available in the form of an Augmented Reality application.

Funding

This systematic review does not get funding.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares there is no conflict of interest in this study.

REFERENCES

- Birt J, Stromberga Z, Cowling M, Moro C. Mobile mixed reality for experiential learning and simulation in medical and health sciences education. Information. 2018;9(2):31.

- Jones F, Passos-Neto CE, Braghiroli OFM. Simulation in medical education: brief history and methodology. Principles and practice of clinical research. 2015;1(2).

- Foronda CL, Alfes CM, Dev P, Kleinheksel AJ, Nelson Jr DA, O’Donnell JM, et al. Virtually nursing: Emerging technologies in nursing education. Nurse educator. 2017;42(1):14–7.

- Arena F, Collotta M, Pau G, Termine F. An Overview of Augmented Reality. Computers. 2022;11(2):28.

- Chiang THC, Yang SJH, Hwang G-J. Students’ online interactive patterns in augmented reality-based inquiry activities. Computers & Education. 2014;78:97–108.

- Di Serio Á, Ibáñez MB, Kloos CD. Impact of an augmented reality system on students’ motivation for a visual art course. Computers & Education. 2013;68:586–96.

- Khan T, Johnston K, Ophoff J. The impact of an augmented reality application on learning motivation of students. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction. 2019;2019.

- Jeffries PR. A framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating: Simulations used as teaching strategies in nursing. Nursing education perspectives. 2005;26(2):96–103.

- Aebersold M, Voepel-Lewis T, Cherara L, Weber M, Khouri C, Levine R, et al. Interactive anatomy-augmented virtual simulation training. Clinical simulation in nursing. 2018;15:34–41.

- Scalese RJ, Issenberg SB. Effective use of simulations for the teaching and acquisition of veterinary professional and clinical skills. Journal of veterinary medical education. 2005;32(4):461–7.

- Hamacher A, Kim SJ, Cho ST, Pardeshi S, Lee SH, Eun S-J, et al. Application of virtual, augmented, and mixed reality to urology. International neurourology journal. 2016;20(3):172.

- Bajura M, Fuchs H, Ohbuchi R. Merging virtual objects with the real world: Seeing ultrasound imagery within the patient. ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics. 1992;26(2):203–10.

- Cameron C. How augmented reality helps doctors save lives. Read Write Web. 2010.

- De Paolis LT, Ricciardi F, Dragoni AF, Aloisio G. An augmented reality application for the radio frequency ablation of the liver tumors. In: International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications. Springer; 2011. p. 572–81.

- Pandya A, Siadat M-R, Auner G. Design, implementation and accuracy of a prototype for medical augmented reality. Computer Aided Surgery. 2005;10(1):23–35.

- Rolland JP, Biocca F, Hamza-Lup F, Ha Y, Martins R. Development of head-mounted projection displays for distributed, collaborative, augmented reality applications. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments. 2005;14(5):528–49.

- Sielhorst T, Obst T, Burgkart R, Riener R, Navab N. An augmented reality delivery simulator for medical training. In: International workshop on augmented environments for medical imaging-MICCAI Satellite Workshop. 2004. p. 11–20.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–58.

- Parmaxi A, Demetriou AA. Augmented reality in language learning: A state‐of‐the‐art review of 2014–2019. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 2020;36(6):861–75.

- Kobayashi L, Zhang XC, Collins SA, Karim N, Merck DL. Exploratory application of augmented reality/mixed reality devices for acute care procedure training. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;19(1):158.

- Majima Y, Masuda S, Matsuda T. Development of Augmented Reality in Learning for Nursing Skills. In: MEDINFO 2019: Health and Wellbeing e-Networks for All. IOS Press; 2019. p. 1720–1.

- Chien C-H, Chen C-H, Jeng T-S. An interactive augmented reality system for learning anatomy structure. In: proceedings of the international multiconference of engineers and computer scientists. International Association of Engineers Hong Kong, China; 2010. p. 17–9.

- Ferrer-Torregrosa J, Torralba J, Jimenez MA, García S, Barcia JM. ARBOOK: Development and assessment of a tool based on augmented reality for anatomy. Journal of Science Education and Technology. 2015;24(1):119–24.

- Drapkin ZA, Lindgren KA, Lopez MJ, Stabio ME. Development and assessment of a new 3D neuroanatomy teaching tool for MRI training. Anatomical sciences education. 2015;8(6):502–9.

- Licci M, Thieringer FM, Guzman R, Soleman J. Development and validation of a synthetic 3D-printed simulator for training in neuroendoscopic ventricular lesion removal. Neurosurgical focus. 2020;48(3):E18.

- Islam G, Kahol K, Ferrara J, Gray R. Development of computer vision algorithm for surgical skill assessment. In: International Conference on Ambient Media and Systems. Springer; 2011. p. 44–51.

- Fairén M, Moyés J, Insa E. VR4Health: Personalized teaching and learning anatomy using VR. Journal of medical systems. 2020;44(5):1–11.

- Pringle RM, Dawson K, Ritzhaupt AD. Integrating science and technology: Using technological pedagogical content knowledge as a framework to study the practices of science teachers. Journal of Science Education and Technology. 2015;24(5):648–62.

- Rao A, Tait I, Alijani A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of mental training in the acquisition of technical skills in surgery. The American Journal of Surgery. 2015;210(3):545–53.

- Herrlin S V, Wange PO, Lapidus G, Hållander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2013;21(2):358–64.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

KNOWLEDGE AND ATTITUDES BETWEEN NURSES, MIDWIVES AND STUDENTS ABOUT VOLUNTARY TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY: A SCOPING REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Sofia Di Mario1, Andrea Minciullo2 & Lucia Filomeno3*

- RN, MSN, PhD Student; Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy.

- RN, MSN, Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Campus Bio-Medico, 00128, Rome, Italy,

- RN, MSN, PhD Student; AOU Policlinico Umberto I – Department of Neurosciences and Mental Health, Viale dell’Università, 30, 00185, Rome, Italy.

* Corresponding author: Lucia Filomeno, Department of Neurosciences and Mental Health, AOU Policlinico Umberto I, Rome. E-mail: lucia.filomeno@uniroma1.it

Cita questo articolo

ABSTRACT

Background: Voluntary termination of pregnancy (VTP) is influenced by ethical convictions, religious orientations and knowledge of the law. The latter is essential for students to be improved in University curricula, in order to develop attitudes among future nurses and midwives with the objective to reduce stigma and reluctance in providing VTP. Previous research has shown that nursing and midwifery students' attitudes and knowledge can be improved.

Aim: The aim of this study is to describe literature regarding knowledge and perception about abortion and voluntary termination of pregnancy in several countries of the world among nurses, midwives and university students.

Methods: This is a scoping review of the literature conducted by following the recommendations of the PRISMA-ScR Statement. The authors selected studies in MEDLINE, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Academic Search Index, Science Citation Index and ERIC, published in English and Italian in the last decade. Quality assessment was performed using the Jadad scale.

Results: Initially, 434 studies were selected. A total of 11 articles met the inclusion criteria. The articles included in the scoping review deal with the issue of abortion from different perspectives. From the analysis it emerged that the barriers for VTP are the lack or inadequate knowledge of the legislation and of the practical / technical phases of the procedure.

Conclusions: Health professionals and students have different perspectives and attitudes toward VTP. Nurses and midwives have inadequate knowledge of procedures and legislation. Therefore, it is recommended to implement university curricula on the topic.

Keywords: knowledge, attitudes, voluntary termination of pregnancy, nurses, midwives, students.

INTRODUCTION

Abortion, originated as birth control, is the termination of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation or with the foetus weight less than 500 gr at birth [1,2]. It can happen when at least three events occur: spontaneous or habitual abortion (also called Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy - VTP), criminal or illegal abortion, and therapeutic or legal abortion [3]. In the last decades of the 20th century, many countries all over the world legalised this practice. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that 3 out of 10 (29%) of all pregnancies, and 6 out of 10 (61%) of all unintended pregnancies, ended in an induced abortion [4]. In many societies, a deep conflict about the legality and morality of abortions manifests itself in restrictive laws and strong antiabortion attitudes. Women, including adolescents, with unwanted pregnancies often resort to unsafe abortion when they cannot access a safe one. Barriers to accessing safe VTP include: restrictive laws, poor availability of services, high cost, stigma, conscientious objection of health-care providers and unnecessary requirements, such as mandatory waiting periods, mandatory counselling, provision of misleading information, third-party authorization, and medically unnecessary tests that delay care [5,6]. Kumar et al. [7], defined abortion stigma as “a negative attribute ascribed to women who seek to terminate a pregnancy that marks them, internally or externally, as inferior to the ideals of womanhood”. According to this definition, women who experience VTP challenge social norms regarding female sexuality and maternity, and their doing so elicits stigmatising responses from the community. Where opposition to abortion is widespread, abortion-related stigma is likely to negatively influence women’s abortion experience.

Increased knowledge and improved attitudes among health care providers and university students have the potential to reduce stigma and reluctance to provide abortion [6]. In a recent study conducted by O'Shaughnessy et al. [8], it was reported that “low levels of knowledge among staff suggests that training is required to ensure the provision of a safe and effective VTP service”. Midwifery and Nursing schools do not provide termination of pregnancy education or, if they do, it is inadequate and so, most staff were left to navigate this procedure without support or prior practice.

Termination is only possible in the rarest of cases: when the pregnancy poses a serious risk to the woman’s life or in the event of foetal malformations [7]. In Italy, as in many countries, it is set at 12 weeks’ gestation according to the law No. 194 enacted on May 22nd, 1978. Before that date, VTP was considered illegal by the criminal code [9]. The law regulates VTP with the aim of guaranteeing the bio-psycho-social integrity and well-being of women. A woman can have an abortion within the first 90 days, or within the fourth and fifth months only for therapeutic reasons [9]. Conscientious objection status does not exempt the professional from assisting the woman before and after the procedure, but from carrying out only those procedures directed towards and aimed at the termination [10-13]. The nurse can raise a conscientious objection to assisting the VTP with a declaration that can be withdrawn at any time [9]. Termination is a woman’s right, and the staff involved must act in accordance with the law and the woman’s right to free choice. A better understanding of factors influencing perceptions may be useful in determining the curricula of university programs and in giving nurses and midwives the tools to cope with their own beliefs towards late abortions [14-16]. Thus, this review seeks to contribute to research on abortion stigma by exploring literature regarding attitude, knowledge and perception differences toward abortion among nursing, midwifery and students, assessing the scientific evidence available to date and thereby delineating directions for future research.

METHODS

Identification of Relevant Studies