Sara Muzzicato1, Lorenza Garrino2, Vincenzo Alastra2, Valeria Miazzo1

- Opera San Camillo Foundation, Turin

- Master Executive Narrative Practices in Care Professions, COREP, Turin

*Corresponding author: Sara Muzzicato, Department of Rehabilitation, Recovery and Functional Rehabilitation Level 2, Fondazione Opera San Camillo, Turin. Email: sara.muzzicato@gmail.com

Cita questo articolo

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Following the Covid-19 pandemic, healthcare personnel had to face a very difficult period linked to the healthcare emergency, with important repercussions from a professional and personal point of view. These aspects have been explored by numerous researches on an international level, but only a small number of articles have investigated the phenomenon in the Italian context. The aim of this research is to describe the experience of healthcare workers in a Covid ward, exploring their emotional responses.

Materials and Methods: The study consists of a qualitative research with a phenomenological approach according to Giorgi. Narrative interviews were used with healthcare workers who worked in a Covid ward at the San Camillo health centre in Turin, a hospital specialising in second level functional recovery and re-education.

Results: Through the field research, 12 interviews were collected, involving 9 nurses and 3 social-health workers, working in a ward dedicated to the care of Covid-19 patients. The common themes that emerged concerned: the beginning of the Covid operator’s “journey”, characterised by a profound change in professional life since the beginning of the pandemic; the whirlwind of emotions and feelings experienced (fear, feeling blocked, annulled, powerless, depersonalised by suits and masks, anguish due to both physical and psychological isolation, etc.); relations with family members and friends; the relationship with the patient’s family; relations with the operators’ families; the risk of contagion and the fear of infecting oneself and one’s loved ones; the group as a handhold for not giving up, as a point of strength, union and trust; the awareness of change with the desire to take one’s own life back into one’s own hands, taking advantage of the good things this time can give.

Conclusions: The research highlights the ability of the operators to identify positive aspects in the experiences lived, the union and trust in the group and the support of the family despite the strong fear of contagion. There are also important suggestions to reinforce strategies for dealing with such health emergencies and the importance for each individual in feeling accompanied throughout the process, in the difficult challenges they face.

Keywords: Covid-19, Experiences, Nursing, Narrative, Phenomenological approach.

INTRODUCTION

On 31 December 2019, Chinese Health Authorities reported to the World Health Organisation a cluster of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology in the city of Wuhan, in China’s Hubei province. On 9 January 2020, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention of China reported that a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)[1] was identified as the causative agent of the respiratory disease later named Covid-19. China made public the genome sequence that enabled a diagnostic test and on 30 January 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO)[2] declared the Coronavirus outbreak in China to be an “International Public Health Emergency” [3,4]. From then on, the word ‘COVID-19’ has indicated the disease associated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), characterised by mild symptoms (fever, sore throat, fatigue, muscle pain, loss of taste and smell) or more severe symptoms (pneumonia, respiratory failure)[5]. Such symptoms have often led to the need for intensive care[6,7], thus causing high pressure on hospitals struggling to cope with too many patients to care for [8]. In this catastrophic scenario linked to the epidemic, Italy was one of the countries most affected[9]. Between the beginning of February and 30 November 2020, 1,651,229 positive Covid-19 cases were diagnosed by Regional Reference Laboratories and reported to the Italian National Institute of Health (NIH) – Italian National Integrated Surveillance System by 20 December 2020[10].

The pandemic has had different intensities and lethality in Italy compared to the rest of Europe. Differences in lethality rates are explained by: demographics, as mortality tends to be higher in older populations with co-morbidities; characteristics of the healthcare system, where there are organisational shortcomings, initial delays in understanding the severity of the emergency, deficits in infection tracking systems, hospitals overwhelmed by admissions, etc.; differences in the number of people tested; and different levels of virus aggressiveness[11].

Italy faced an unprecedented health crisis, with serious shortages of health professionals and difficulties in procuring personal protective equipment. New organisational models had to be implemented and hospital inpatient facilities had to be rapidly transformed into units suitable for the care of pandemic patients[12].

The NIH weekly bulletin of 28 April 2020 stated that 47.4% of the cases of infection among healthcare personnel were nurses[13].

In Italy[14] according to the provincial records, 40 nurses died, 32 of whom with the Covid-19 disease (positive swab), 4 with Covid-related illness (for whom the viral pathology was a favourable factor) and 4 (positive in any manner) for whom the mode of death was suicide[15]. A different view of the same phenomenon is reported by the monitoring as of 15 June 2020 conducted by INAIL (Italian National Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work). INAIL, considering the accident reports referring only to insured workers, certified that there were a total of 236 deaths from Covid-19, of which 40% were healthcare professionals and 61% were nurses. In this complex epidemiological and healthcare framework, healthcare personnel reported the consequences of significant psychophysical stress with experiences and emotions still largely to be explored. Arasli et al. (2020)[16] explored experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic through testimonies written by nurses on social media through qualitative research. The study showed a high level of stress among healthcare professionals related to the risk and fear of becoming infected. Labrague et al. (2020)[17], through a quantitative study conducted in a region of the Philippines, highlighted high dysfunctional levels of anxiety in frontline nurses, while recording an increase in their resilience. On the Italian scene, Catania et al. (2020)[18] carried out qualitative research involving nurses from all regions of the peninsula. This study highlighted the enormous impact of COVID-19 on nurses, the need to identify new working practices, and highlighted the high-risk nature of nursing, exacerbated by the difficulty in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) availability. In addition to reporting the high levels of stress experienced by the interviewees, the element of narratives also highlighted the resilience of the nursing community. Qualitative research was conducted by De Vito et al.[19], through the narratives of paediatric doctors and nurses in the paediatric emergency room of the Regina Margherita hospital. The authors emphasise how much the number of admissions in the paediatric sector had fallen, reflecting profoundly on changes in care, but also on the relationship itself with and between patients.

The results of the study show how the act of describing helped participants to process and understand their experience. Storytelling provided a cathartic means for participants to reformulate the events they experienced, rationalising them and making sense of them. In the Turin landscape, the experiences of nursing students were investigated. Garrino et al. (2021)[20], through a qualitative study, emphasised the changes induced by Covid-19 in nursing education. The need to use distance learning and the impossibility of doing internships during the pandemic period created many difficulties in training students. The narrative approach[21] and reflective thinking[22] aim to capture the latent aspects and hidden meanings of the complex pandemic reality[23,24].

The aim of the research is to describe the experience of health workers on a Covid ward, exploring their experiences and emotions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

In this study, a qualitative methodology was used to investigate subjective phenomena, based on the assumption that fundamental truths about reality are rooted in people’s lived experiences. This method allows for exploration of experiences by the person who has them, attempting to describe the meanings that the individual creates and gives to that experience, understanding the structure, nature and form, as perceived by the individual[25]. This survey aims to understand the experience of nurses and social workers during the first wave in a ward caring for Covid-19 patients, and who are now called upon again to provide the same type of care, in order to find out how the workers in question have responded to a pandemic emergency which, in addition to involving the work aspect, has invaded the personal sphere.

Background

The San Camillo hospital, as a hospital specialising in second-level functional recovery and rehabilitation, provides intensive rehabilitation treatment in the post-acute phase of the illness. The hospital has five departments that fulfil this function.

In November 2020, during the second wave of the pandemic, two wards were dedicated to the care of Covid patients. The health workers of these two wards, defined as ‘COVID staff’, had to cope with this new situation with various difficulties that have also characterised many healthcare facilities in Italy, but in this second phase they were able to use sufficient and appropriate PPE. The COVID wards of the facility were designed for a maximum capacity of 20 beds and intended for the care of patients coming from the intensive care units of other hospitals and in the sub-acute phase. Other patients in the early stages of the disease came directly from the emergency rooms of local hospitals, which could not cope with all the demand at that time. During admission, the intention was to stabilise the clinical condition and ventilatory support consisted of a Venturi mask or nasal cannulae, not having the tools provided in intensive care, such as assisted ventilation or intubation of the patient. The hospitalisation continued until the swab was negative, although the symptoms had already receded. Few of these patients died in the facility. The research was conducted in only one of the two Covid departments (with the participation of three respondents who worked in the second department, but who had worked sporadic shifts in the Covid department under consideration).

Participants

In this study, nurses and social workers (OSS) working in the Covid ward of the San Camillo hospital in Turin agreed to participate. Participants include the researcher (MS), in the role of observer-participant.

Mode of data collection

The study was based on a collection of semi-structured interviews consisting of 11 open-ended questions (Box 1) and proposed directly to the persons involved by email[26,27]. Respondents participated on a voluntary basis. Non-probabilistic, purposive sampling continued until data saturation, collected between 15 December 2020 and 15 January 2021. The questions for the semi-structured interviews were elaborated with the narrative interview method[28] and were chosen through the “SIFA” method, in order to try to explore each sphere of interest regarding Feelings, Ideas, Functions/Activities of the client, Expectations[29].

Methods of data analysis

For data analysis, the phenomenological method according to Giorgi (2008)[30] was used (Box 2). The interviews were read over and over again, seeking personal assessments through a suspension of judgement. Subsequently, an attempt was made to find common areas of meaning describing the most important themes reported by the interviewees[31,32]. The analysis was conducted independently by researchers S.M., L.G., V.A. and V.M. They then compared their work using the triangulation method[33]. During the analysis, the researchers reflected on their own values and suspended judgements, knowledge and ideas about the phenomenon under study[34].

Ethical consideration

The persons involved voluntarily agreed to answer the interview and signed an informed consent on the use and processing of the data. The research was authorised by the Health Directorate and the General Directorate of the San Camillo Hospital.

RESULTS

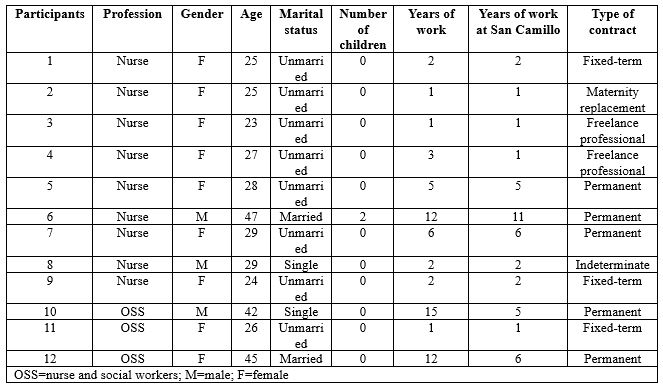

Through field research, 12 interviews were collected. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic data of the participants.

Table 1 – Social and personal data of participants

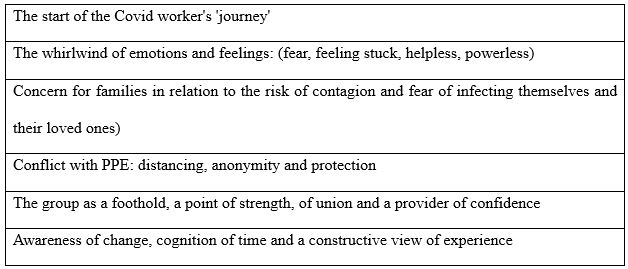

The average age of those involved is 30, with a minimum age of 23 and a maximum age of 47. All operators were professionally trained in Italy. None have postgraduate or Master’s degrees. Several main and recurring themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews. These macro-categories bring us back to the experience of the participants. Terminology as presented and written by the interviewees themselves is reported, outlining the importance of the meanings expressed by them. The following themes emerged: the beginning of the Covid worker’s ‘journey’ and the whirlwind of emotions and feelings that accompanied that (fear, feeling stuck, helpless, powerless, concerns for one’s family in relation to the risk of contagion and the fear of infecting oneself and loved ones), the group as a foothold to keep going, a point of strength, union and provider of trust, the awareness of change, the cognition of time and the constructive vision of the experience (table 2).

Table 2 – Main themes emerging from the analysis

The start of the Covid worker’s ‘journey’

The interviews reveal the profound change that occurred in the participants’ professional lives at the beginning of the pandemic. Most of them talk about the impossibility of choosing whether to work in a Covid department or not, often indicating it as a decision linked to a sense of duty fulfilment.

[…] “It wasn’t really a personal choice to join the Covid team… I happened to be there, and I was probably OK with that.” […] (interview 1)

[…] “I didn’t really have a choice in deciding whether I could work closely with Covid-positive patients… So compared to my start in a Covid department, I can’t even explain how it came about.” […] (interview 3)

Participants underline the initial impact they had following the news, accompanied by a set of feelings that were difficult to deal with at the time and to talk about later. They describe thoughts, emotions and sensations and there are often conflicting feelings, accompanied by fear, anxiety and stress.

[…] “Literally thrown into the deep end… My thoughts were questions. Why? Why? Why? So many questions that had no answers.” […] (interview 8)

[…] “I’m still trying to figure it out… on the front line in a Covid ward… I wasn’t chosen, I found myself there almost by accident.” […] (interview 7)

In the interviews, the theme of travel emerges significantly, as a symbol of uncertainty and restlessness in trying to know and explore unknown places; as well as the theme of battle, almost as if they had to fulfil a destiny already written in their professional profile.

[…] “I didn’t feel chosen, I felt enlisted in an impromptu army for an impromptu battle… I was there, so I had to fight… I had the fear and adrenaline of those who leave without knowing the destination and the consequences of their journey.” […] (interview 4)

A whirlwind of emotions and feelings: fear, feeling stuck, helpless, powerless

Concerning the emotions felt during this long experience by the health workers, many of them found themselves facing different difficulties, multiple fears and feelings, one of the main ones being isolation, not only physical but also psychological.

[…] “I avoided even the contact allowed by the Decrees, I isolated myself completely, more than was necessary… All you can do is wake up in the morning and wonder when it will end… I would have liked to live fully, not at the mercy of anxiety and worry. […] (interview 1)

[…] “I would arrive home drained, feeling nothing but tiredness that muffled all the outside world.” […] (interview 2)

[…] “I see myself as someone who put aside feelings and sensations to face a big battle, so today I don’t even remember what I was feeling… We have lost all consciousness, we no longer saw well, we no longer heard well, we no longer spoke much…” […] (interview 3)

Respondents write that they feel alone in this battle, misunderstood, stuck and aimless, depersonalised, helpless due to the suits and masks, powerless before an invisible enemy so difficult to defeat.

[…] “When I finish a shift, I feel like I have finished a test under stress… as though I had passed a test… many times I felt like I hadn’t made it, as though the ground was sinking from under my feet, other times I felt empty, as though under that suit there was almost nothing left… as if I had failed, as if I hadn’t done enough.” […] (interview 4)

[…] “I remember the fear… and the tiredness because I had been alone in facing that new beginning so physically and psychologically intense… The whole condition of isolation puts a lot of pressure on you psychologically… I felt powerless, a nobody before something so big… I felt like a wrapper, a container whose contents had been disposed of along with the protective suit.” […] (interview 5)

The family and the risk of contagion: the fear of infecting oneself and one’s loved ones

A topic that is repeated in almost every narrative is the importance of family affection. This theme is often addressed in the interviews, emphasising the importance that health workers attached to the support given by their loved ones, but at the same time linked to the constant fear of infecting themselves and consequently their families.

[…] “If I get infected will I be sick? And at home? If mum and dad get ill? Who will take care of Granny if we are sick? What if Granny gets sick?” […] (interview 1)

[…] “I was afraid though, afraid of not being up to it and afraid of infecting myself and my loved ones.” […] (interview 2)

[…] “The biggest fear I had was that I would get worse and that I could infect my partner… that last idea drove me mad.” […] (interview 5)

There was a high level of stress among the interviewees, which, despite everything, also contributed to an increase in attention and precautions regarding safety regulations, the correct use of personal protective equipment and the correct way of disposing of it.

[…] “At the onset, I didn’t have tumultuous emotions, it was the people next to me who were really very worried and I honestly experienced their emotion… The first thing I think about when I start my shift is that I must not get sick, so I must do everything I can to avoid infection.” […] (interview 3)

[…] “I try to be focused because you can let your guard down due to tiredness and then risk getting infected.” […] (interview 12)

Conflict with PPE: distancing, anonymity and protection

The interviews reveal the perceptions of nurses and social workers obliged to wear “all those layers of latex”, exploring their experiences in relation to the care provided to their patients on the Covid ward. Nurses and social workers talk of overalls, double gloves, double masks, footwear, goggles and face shields which, while vital for working on Covid wards, have raised barriers between staff and patients.

[…] “A person covered from head to toe without knowing what he looks like or not remembering his name, as if he wasn’t human… and all I know of this person are his brown eyes surrounded by a mask and a big suit.” […] (interview 1)

[…]“”Halfway between astronauts and aliens!” […] (interview 2)

[…]“I never imagined that I would keep my physical and moral distance from a patient in such a way that I could become one of the many operators, just any operator, someone easily replaceable… I didn’t use to feel naked unless wearing a gown, visor and mask, whereas now I do.” […] (interview 3)

[…]“”So many little white men, completely covered by overalls, gowns, masks, gloves and visor, almost clumsy in their movements and practically indistinguishable from each other… What I miss most is being able to show my smile to the patients, free from masks, and to shake their hands, free from those multiple layers of gloves.” […] (interview 5)

[…]“Living diving suits… it’s as though there were a thousand barriers, a thousand layers separating us…a gentle caress with double latex gloves is not the same…”[…] (interview 6)

The group as a foothold for not giving up: strength, unity and trust

From the interviews, it emerges that the group has been a strong point, an important support for the health workers to go on and not give up.

[…] “I have never believed in the motto ‘unity is strength’ as I do now… in April there were so many brave little soldiers, in November we were one giant soldier…I don’t feel alone, never; I feel escorted, I feel that someone is looking out for me as I am looking out for someone else… the working group has become a family… I would get through this as long as I had this team to rely on.” […] (interview 4)

[…] “I am grateful to her for that moment, for understanding me and giving me strength when she was probably also on her last legs. We hugged each other when we left the hospital, amidst tears. I don’t think I could have done it without her that day.” (Interview 6)

[…] “We have been able to overcome some difficult moments only thanks to our unity. (Interview 7)

According to the interviewees, coping with such a complex period with one’s team helped to increase cohesion, strengthen group dynamics and was often the driving force needed to cope with stressful situations.

[…] “The wonderful team I have the honour of sharing this experience with has become very cohesive. We all worked together for the same goal on the same road, holding hands, hugging ideally, supporting each other, experiencing the same feelings, falling down and helping each other up.” […] (interview 3)

[…]“”I believe that the greatest strength came from the working group, which I have never before felt close to me, or rather part of me… in the group set up for the Covid emergency, I really found a rock to rely on. We work with common principles, side by side to achieve the same goals. What I perceive between us is harmony, respect and sharing”[…] (interview 5)

Awareness of change: time, self-work, constructive view of the experience

What emerges from the interviews is the strength and the desire to take charge of one’s own life again, the desire to make it through this pandemic, trying to find a positive side, not to throw everything away, to seize what good can come from this experience. From the words of those interviewed, one can see a devastating past and present, which has affected people greatly, but also a future full of hope.

[…] “I hope to be myself with some more awareness, especially about what was taken for granted before Covid… I’m happy to still feel like myself, to not want to give in to the suffering that Covid forced us to face every day.” […] (interview 2)

[…]“”I worked on myself like we all did…The nurse I loved to be is here somewhere, she is not gone… My job will go back to that wonderful normality I loved, with some more experience, some scars that won’t go away, some indelible memories…”[…] (interview 4)

[…]“”I hope to still be the same, with more experience on my shoulders. Of course, the pandemic has changed everything and everyone, but life goes on and you have to think about facing the next enemy.”[…] (interview 8)

[…]“”I hope to see myself proud of what I have done, I hope to have left a good memory in the people I have met and I will be able to say this one is gone too.” […] (interview 12)

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to describe the experience of healthcare workers in a Covid ward, exploring their emotional experiences and attempting to capture the meanings that the individual creates and gives to that experience, understanding the structure, nature and form, as perceived by the individual. This survey collected the experiences of nurses and social and health workers who worked in a ward for the treatment of patients affected by Covid-19, in order to know how they responded to an emergency situation that not only involved the work aspect but also invaded the personal sphere. From the data collected, it emerges that the pandemic is immediately experienced by health workers as insidious, bringing uncertainties and anxiety, emotions and feelings that can be traced back to a scenario reminiscent of a battle. You feel overwhelmed by a storm, you prepare for the arrival of a real ‘enemy’ [19], you find yourself united by the same feelings, but at the same time alone and ill-prepared, forced to take the to the field with the few weapons available. This describes the whirlwind of emotions, fears, worries, feelings of helplessness, a mixture of negative feelings in which there is rarely any slight hope for the future. In the interviews, all subjects tell of their fears: of becoming sick and infected, of being isolated, of not being ready to face the big changes in the work structure. This issue is dealt with extensively by Catania et al.[18] and by De Vito et al.[19], highlighting how the narratives of the nurses, also working in different wards, underline the common theme of the physical and psychological impact that the change in work organisation had on the same individual workers and on team work. In the study by Arasli et al[16], ‘fear’ and ‘risk’ were two of the most frequently used words by nurses in social media during the pandemic. Among the feelings experienced there is certainly no lack of anxiety, which is expressed several times in the narratives considered in this study and is also widely described in the article by Labrague et al.[17]. From the data collected it emerges how the entire pandemic situation forces nurses and social and health workers to create a different way of being workers, a situation that almost imposes a different way of directing the therapeutic relationship no longer mediated by touch, words, reciprocal dialogue and the security of familiar clothing, but hindered by the trappings of a distancing “dress” and by the impossibility of speech that bring out a problematic core of objectification of care. This aspect emphasises how to deal with health emergencies, without at the same time renouncing the humanity of the therapeutic relationship that characterises this profession. All the images described in the interviews are of ‘detachment’ from one’s own body which, within the innumerable protective layers within which it is forced, finds itself taking on a form unknown to the eyes of the subjects themselves. These people are the same as those who performed acts of care, but in doing so they all felt equal and experienced a human closeness made up only of glances. From the narratives of this research, a strong spirit of adaptation and resilience emerges in nurses, aspects also described by Catania et al.[18] and Labrague et al.[17]. This theme was widely taken up in the interviews, allowing us to outline through these nurses “made of suits and personal protective equipment”, an image in which latex and nitrile are transformed into a material capable of absorbing a shock without breaking, to face and overcome a traumatic and extreme event, to give hope in the future. Wu Y. et al. [35] show that doctors and nurses working in Covid wards experienced lower levels of anxiety, depression and burnout than those working in their usual wards, with a response to the pandemic characterised by a high level of adaptation and resilience. The participants of our study emphasised that the team proved to be the most important strength in overcoming daily difficulties within the Covid department. The objectives for which the group meets and works together and the dynamics of consolidation of the process that forms the working group, from interaction to integration[35], are essentially described in both processes and activities: the group intervenes whenever someone is in difficulty; a hand is always extended towards the other when one finds oneself lost in what should be a known world but has become an unexplored labyrinth. The feeling of belonging to the group is found to be a decisive positive factor also among the students of the article by Garrino et al.[20], which underlines how the comparison between peers and the support provided by peers are a decisive element to deal positively with the practical traineeship experience.

Another important theme that emerged from the interviews was time. A time that sometimes expands, sometimes shrinks, but which must be lived anyway[19]. In fact, the impact of the pandemic marked a deep rift between what was before and what would be after. This perception had different effects. On the one hand, it made them feel stuck and unable to imagine the future from such an uncertain present; on the other hand, it allowed them to discover new physical spaces and adopt new or renewed daily habits which helped them to imagine a possible future. The perspectives described are linked to fear, but also to the hope that normality will be re-established, both on the horizon of care and in daily life. These reflections represent an added value that contributes to a greater understanding of oneself and the role that one’s experiences played during the emergency. Narratives have been a useful tool for making sense and meaning of the experiences associated with the pandemic experience[19].

CONCLUSIONS

The research explored the lived experiences of a small group of health workers working in a Covid ward during the pandemic in November 2020. Telling stories was a chance to give shape to the situations experienced, continuing to plan oneself, giving new meaning and significance to one’s existence. Narrative and mutual listening practices were recognised as very useful and effective in capturing and understanding meanings, emotions and representations about one’s professional role and wider existential issues. This research provides evidence to improve the strategies to deal with a health emergency by listening to personal experiences and thoughts, by accepting the emotions and feelings felt by the care professionals, experiences and representations that, many times, in these situations the caregiver may struggle to express or, even, prefers to keep hidden under his uniform. It can be concluded that narrative medicine used in care environments, in situations where there is no space and time for the individual, offers the possibility to improve and increase the communication and cooperation skills of all; to develop new knowledge of each operator to improve the relationship with others; to give meaning and value to the experience of care of health workers and help them to process and alleviate, as far as possible, the emotional stress that accompanies them in the difficult path of care.

LIMITATIONS

Data were collected by sending an interview outline via email. This method was chosen due to the lack of opportunities to conduct the interview due to the national lock-down and to allow the interviewees to express themselves freely and openly without time constraints. this deprived the research of elements concerning the conducting and interaction aspects that usually characterise face-to-face interviews.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST AND FUNDING SOURCES

No funding sources were used to support the project. There is no conflict of interest.

DECLARATIONS

No formal approval by the Local Ethics Committee was required for this study.

REFERENCES

- Tutto sulla pandemia di SARS-CoV-2; 16 gennaio 2020. Disponibile a:https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/sars-cov-2. Ultimo accesso 28 febbraio 2022.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Disponibilea: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Ultimo accesso 7 marzo 2022.

- Tufekci Z. Pandemic mistakes we keep repeating. The Atlantic. 26 febbraio, 2021. Disponibile a: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/02/how-public-health-messaging-backfired/618147/. Ultimo accesso 20 febbraio 2022.

- WHO Director-General’s opening remarksat the media briefing on COVID19; 23 ottobre 2020. Disponibile a:https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—23-october-2020. Ultimo accesso 20 gennaio 2022. Ultimo accesso 10 febbraio 2022.

- Contini C., Di Nuzzo M., Barp N., Bonazza A., De Giorgio R., Tognon M., et al.The novel zoonotic COVID-19 pandemic: An expected global health concern. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 254–264.

- Covid-19: mortalità in terapia intensiva; 2 ottobre 2020. Disponibile a: https://www.med4.care/covid-19-mortalita-in-terapia-intensiva/. Ultimo accesso 7 marzo 2022.

- Porcheddu R., Serra C., Kelvin D., Kelvin N., Rubino S. Similarity in Case Fatality Rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 in Italy and China. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 125–128.

- Galimberti F., Boseggia S.B., Tragni E. Consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare services. SEFAP Università degli Studi di Milano 2021; 13 (1): 5-16. Disponibile a: http://www.sefap.it/web/upload/GIFF2021_1_5_16.pdf. Ultimo accesso 10 febbraio 2022.

- Impatto dell’epidemia COVID-19 sulla mortalità totale della popolazione residente periodo gennaio-novembre 2020; 30 dicembre 2020. Disponibile a: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/pdf/Rapp_Istat_Iss_gennaio-novembre-2020.pdf- Ultimo accesso 20 gennaio 2022.

- La mortalità totale in Italia nell’anno della pandemia; 16 febbraio 2021. Disponibile a: https://www.unive.it/pag/fileadmin/user_upload/dipartimenti/economia/doc/eventi/EconomicsTuesdayTalks/ett_20210216_corsetti.pdf. Ultimo accesso 4 marzo 2022.

- Sun P., Lu X., Xu C., Sun W., Pan B. Understanding of COVID-19 based on current evidence. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 548–551.

- Epidemia COVID-19; 30 aprile 2020. Disponibile a: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_28-aprile-2020.pdf. Ultimo accesso 20 gennaio 2022.

- COVID-19, l’impatto della pandemia: analisi degli infermieri deceduti; 15 luglio 2020. Disponibile a: https://www.fnopi.it/2020/07/15/covid19-analisi-deceduti-infermieri. Ultimo accesso 20 gennaio 2022.

- Rizzo C., Campagna I., Pandolfi E., Croci I., Russo L., Ciampini S., et al. Knowledge and Perception of COVID-19 Pandemic during the FirstWave (Feb–May 2020): A Cross-Sectional Study among Italian HealthcareWorkers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18, 3767.

- Monitoraggio sugli operatori sanitari risultati positivi a COVID-19 dall’inizio dell’epidemia fino al 30 aprile 2020: studio retrospettivo in sette regioni italiane; marzo 2021. Disponibile a https://www.inail.it/cs/internet/docs/alg-pubbl-monitoraggio-operatori-sanitari-studio.pdf. Ultimo accesso 7 marzo 2020.

- Arasli H., Furunes T., Jafari K., Saydam M.B., Degirmencioglu Z. Hearing the Voices of Wingless Angels: A Critical Content Analysis of Nurses’ COVID-19 Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 16;17(22):8484. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228484.

- Labrague L.J., De Los Santos J.A.A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020 Oct; 28(7):1653-1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121.

- Catania G., Zanini M., Hayter M., Timmins F., Dasso N., Ottonello G., et al. Lessons from Italian front-line nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2021;29(3):404-411. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13194.

- De Vito B., Castagno E., Garrone E., Tardivo I., Conti A., Luciani M., et al. Narrating care during the COVID-19 pandemic in a paediatric emergency department. Reflective Practice. 2021: 1-12 doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.2013190.

- Garrino L., Ruffinengo C., Mussa V., Nicotera R., Cominetti L., Lucenti G., et al. Diari di bordo: l’esperienza di tirocinio pre-triage COVID 19 degli studenti in infermieristica. Journal of Health Care Education in Practice. 2021; 3, 67-79.

- Charon R. Narrative medicine – Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York: Oxford University Press. it. Medicina narrativa. Onorare le storie dei pazienti. Milano, Raffello Cortina Editore 2019.

- Mortari L. Ricercare e riflettere. Roma: Carocci Editore. 2009.

- Sodano L. Emozioni Virali. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore.

- Bosco F., Chiarlo M., Tizzani D., Cavicchi Z.F. Abbracciare con lo sguardo. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore. 2020.

- Polit D.F., Beck C.T. Fondamenti di ricerca infermieristica. Seconda edizione Milano: McGraw-Hill Education. 2018; 3.

- Liehr P., Takahashi R., Liu H., Nishimuna C., Summers L.C. Bridging distance and culture with a cyberspace method of qualitative analysis. AdvNurs Sci. 2004; 27(3):176-186.

- Hamilton R.J., Bowers B.J. Internet recruitment and e-mail interviews in qualitative studies. Qual Health Res. 2006; 16:821- 835.

- Atkinson R. L’intervista narrativa. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.

- Hogan-Quigley B., Palm M.L., Bickley L.B. Valutazione per l’assistenza infermieristica. Rozzano: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana. 2017.

- Giorgi A.P., Giorgi B. Phenomenological psychology: The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology. 2016. doi: 3402/qhw.v11.30682

- Garrino L. La Medicina narrativa nei percorsi di ricerca e di cura in Finiguerra I., Garrino L., Picco E., Simone P. Narrare la malattia rara. Esperienze e vissuti delle persone assistite e degli operatori. Torino: Edizioni Medico-Scientifiche.

- Mortari L., Zannini L. La ricerca qualitativa in ambito sanitario. Roma: Carocci Editore. 2017.

- Streuber Speziale H.J., Carpenter D.R. La ricerca qualitativa: un imperativo umanistico. Napoli: Idelson-Gnocchi. 2005.

- Mortari L., Ghirotto L. I metodi dalla ricerca qualitativa. Roma: Carocci Editore. 2019.

- Wu Y., Wang J., Luo C., Hu S., Lin X., Anderson A.E., et al. A Comparison of Burnout Frequency Among Oncology Physicians and Nurses Working on the Frontline and Usual Wards During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.2020;60.

- Quaglino G.P., Casagrande S., Castellano A.M. Gruppo di lavoro, lavoro di gruppo. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore. 1992.

Box 1 – Interview outline

1. Could you tell me how your adventure in the Covid ward started?

2. What was the first thought that came into your mind when you were chosen as Covid-19 worker?

3. How do you think your way of working has changed compared to before?

4. If you saw yourself through the eyes of a patient, how would you describe yourself?

5. How do you feel and what do you think when you finish your shift and leave the hospital?

6. And what do you think and feel when you have to start a shift?

7. has anything changed in the working group compared to previous months? If so, what?

8. Can you tell me an episode that made you think you could deal with all this with your team?

Box 2 – Giorgi’s method (2008)

A. Read the whole description of the experience with the aim of making sense of it all

B. Rereading the descriptions to discover the essences of the experience. Observe every time a transaction takes place in meaning. Make these meaning units or themes abstract

C. Examine units of meaning for redundancy, clarification or elaboration. Relate units of meaning to each other and to the meaning of the whole

D. Reflect on the units of meaning and extrapolating the essence of the experience for each participant. Transform each unit of meaning into scientific language

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.