How Deep Are the Invisible Wounds? The Impact of Maternal Stress During Pregnancy on Adolescent Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Study

Dessy Ekawati 1*, Nurul Azmi Arfan 2, Esti Pratiwi Yosin 2, Endang Yuswatiningsih 3

1 Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health, Institute of Science and Health Technology Insan Cendekia Medika Jombang, Indonesia.

2 Department of Midwifery, Faculty of Health, Institute of Science and Health Technology Insan Cendekia Medika Jombang, Indonesia.

3 Vocational Nursing Study Program, Ngawi District Government Nursing Academy, Indonesia.

* Corresponding Author: Dessy Ekawati, Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health, Institute of Science and Health Technology Insan Cendekia Medika Jombang, Indonesia. E-mail: dessyekawati.s1201@gmail.com, +6289624753811

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Background: Pregnancy-related stress can affect a child’s development for a long time, increasing the likelihood of teenage anxiety. High levels of stress hormone exposure during pregnancy may interfere with the development of the nervous system and stress reactions, making a person more susceptible to anxiety disorders.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to determine the degree to which prenatal stress leads to teenage anxiety and to examine the association between maternal stress during pregnancy and teenage anxiety levels.

Methods: A cross-sectional design was used, involving 143 mothers with adolescents aged 10–19 years, selected through purposive sampling. The Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ) was used to measure prenatal stress, while the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) was used to measure anxiety in adolescents. The link between prenatal stress and teenage anxiety was examined using Spearman's correlation, and the impact of prenatal stress on teenage anxiety was ascertained using ordinal regression.

Results: Prenatal stress and teenage anxiety were significantly positively correlated, according to Spearman's correlation test (r= 0.51; p < 0.0001). Ordinal regression analysis indicated that prenatal stress significantly influenced adolescent anxiety (Chi-Square = 27.9; p < 0.0001), explaining 45.6% of its variability (Nagelkerke R²= 0.46).

Conclusion: Maternal stress during pregnancy showed a moderate, significant positive correlation with adolescent anxiety (r= 0.51; p < 0.0001), explaining 45.6% of the variance in anxiety levels. Strengthening psychosocial support for pregnant women and implementing early prenatal stress detection programs are essential strategies to reduce the risk of anxiety disorders in their children. These findings highlight the need for psychological support programs for pregnant women to reduce the risk of anxiety disorders in their children.

Keywords: prenatal stress, adolescent anxiety, maternal anxiety, maternal mental health

INTRODUCTION

Pregnant women face various physical and emotional challenges that can affect their psychological well-being. Stress experienced during pregnancy not only impacts the mother but can also influence fetal development and the child's well-being in the future. Anxiety experienced by adolescents is one of the long-term effects of prenatal stress that is often overlooked [1]. Previous studies have demonstrated that maternal stress during pregnancy is significantly associated with an increased risk of anxiety symptoms in adolescents, suggesting that early life stress exposure may have enduring psychological consequences [2].

Adolescents with a history of mothers experiencing stress during pregnancy are more vulnerable to anxiety disorders compared to their peers. High exposure to stress hormones in the womb has the potential to disrupt the development of the nervous system and the child's stress response later in life. Specifically, elevated levels of maternal cortisol during critical periods of fetal development may alter the structure and connectivity of brain regions involved in emotional regulation, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex [3]. Van Den Bergh et al. (2005) found that prenatal exposure to maternal anxiety alters amygdala connectivity in the fetus, potentially affecting emotional regulation into adolescence [4]. Anxiety in adolescents can significantly affect their social life, academic performance, and mental health. Anxiety's long-term consequences include poorer academic performance, trouble interacting with others, and a higher chance of developing other mental health conditions like depression [5].

Pregnancy can be a period of psychological stress, anxiety, and health concerns. Even in uncomplicated pregnancies, around 20% of women experience excessive worry about future events. Studies suggest that 10-16% of pregnant women are diagnosed with major depressive disorder, while up to 70% experience stress and anxiety. Though the overall prevalence of psychosocial stress during pregnancy remains unclear, research indicates that 22-25% of women experience high stress levels in each trimester [6]. A recent meta-analysis involving over 200,000 pregnant women across 102 studies reported that self-reported anxiety symptoms increased from 18.2% in the first trimester to 24.6% in the third trimester. Meanwhile, clinically diagnosed anxiety disorders were found in approximately 18% of women in the first trimester and 15% in the later stages of pregnancy. This discrepancy may be due to the overlap between depression symptoms and normal emotional fluctuations during pregnancy. Additionally, approximately 6.0–16.7% of pregnant women experience severe stress, while 13.6–91.86% experience mild to moderate stress [7].

Stress during pregnancy can be triggered by various factors, such as economic pressure, household conflicts, lack of social support, and maternal health conditions, including sleep disturbances and prenatal depression [8]. Furthermore, maternal age is important, especially for young moms, who frequently endure higher stress levels as a result of social pressure, mental unpreparedness, and restricted access to quality healthcare facilities. This problem is made worse by ignorance about pregnancy and parenting, which eventually affects the growth of the fetus as well as the health of the mother. Long-term stress can raise the risk of pregnancy issues such gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and preterm birth by interfering with the control of cortisol, which is involved in the body's stress response [9]. Additionally, high exposure to stress hormones in the womb can affect fetal nervous system development, particularly in brain regions responsible for emotional and stress regulation, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Therefore, children of high-stress pregnant moms are more likely to have a lower stress threshold, be more susceptible to psychological strain, and develop anxiety problems during adolescence [10]. A systematic review by Tung et al. (2023) concluded that prenatal stress significantly correlates with increased risk of anxiety and behavioral issues in offspring [11].

Given these findings, it is crucial to better understand how maternal stress during pregnancy may contribute to adolescent mental health outcomes. Preventive efforts can be made by enhancing psychosocial support for pregnant women and providing education on stress management during pregnancy. Maternal mental health programs in healthcare facilities should be strengthened to enable early detection of prenatal stress. Family support and psychological counseling services can also help reduce maternal stress levels, thereby minimizing the risk of anxiety disorders in adolescents later in life [12].

Objective

This study aims to

1) examine the connection between teenage anxiety levels and the stress experienced by the mother during pregnancy, as well as;

2) assess the degree of association between prenatal stress and adolescent anxiety, considering possible confounding factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Sample

This study involved 143 mothers with adolescent children aged 10–19 years as respondents. Based on the Slovin formula with a 5% margin of error, the minimum required sample size for an estimated population of approximately 223 mothers was 143 participants. Participants were recruited from community health centers (Puskesmas) and Community Health Volunteer in Jombang District, East Java Province, Indonesia, through direct invitations and announcements with the assistance of community leaders. Inclusion criteria were:(1) mothers with adolescent children aged 10–19 years; (2) mothers able to recall and describe their experiences during pregnancy; and (3) willingness to participate by signing informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) mothers with a history of severe psychiatric disorders that could affect memory reliability, and (2) mothers whose adolescent children had diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders to avoid potential confounding factors. To minimize selection bias, recruitment procedures were standardized with uniform information sheets and consent forms provided to all candidates, and data collection was carried out by trained researchers. Nevertheless, the possibility of selection bias inherent to purposive sampling cannot be completely ruled out. Although convenience sampling allowed for timely data collection, it may have introduced selection bias and limited generalizability, compared to randomized sampling methods used in similar studies.

Data Collection

Data collection in this study was conducted in Jombang, a district in East Java Province, Indonesia, located in the eastern part of Java Island. The study took place from January 2025 to March 2025, focusing on maternal stress during pregnancy and its relationship with adolescent anxiety levels. A structured and systematic approach was implemented to ensure valid and reliable results.

Prior to data collection, a preliminary pilot test involving 10 participants was conducted to evaluate the clarity, comprehension, and cultural relevance of the instruments. To further improve data quality, several study team members with relevant expertise were involved in reviewing the research tools. Dessy Ekawati, holding a master’s degree in psychiatric nursing and formal training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and statistical data processing, assessed the psychological aspects and clarity of emotional stress-related items. Nurul Azmi Arfan and Esti Pratiwi Yosin, both holding master's degrees in midwifery with a specialization in maternal and adolescent development, evaluated the cultural appropriateness and contextual suitability of the instruments. Their input was utilized to refine item wording, improve sensitivity to the local context, and enhance the comprehensibility of the questionnaires.

The primary data collection was conducted by Dessy Ekawati, with support from Nurul Azmi Arfan and Esti Pratiwi Yosin, to ensure consistency and minimize procedural bias. Endang Yuswatiningsih, a master's graduate in community nursing with expertise in statistical analysis, was responsible for supervising data management and quality control. Throughout the research process, participant anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained to promote honest and accurate responses. This study is part of a broader research initiative investigating the impact of maternal psychological stress during pregnancy on emotional outcomes during adolescence.

Measures

Maternal stress during pregnancy was measured using the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ), while adolescent anxiety was assessed via the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The PDQ contains 12 items across six facets of prenatal stress, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Very often): Baby’s Health & Childbirth, Physical Changes & Pregnancy Symptoms, Relationships & Social Support, Mother’s Role & Responsibilities, Financial & Career Concerns, and Mental & Emotional Health. Total scores range from 12 to 60, and were categorized as follows: low (12–27), moderate (28–43), and high (44–60). A validity test using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed that all items had a loading factor greater than 0.40, while the reliability test with Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85 indicated good internal consistency. To ensure cultural relevance, the PDQ instrument used has been validated in the Indonesian context [13],

Teenagers' anxiety levels for the previous two weeks were evaluated using the GAD-7. It consists of seven items classified into None/Minimal Anxiety (0–4), Mild Anxiety (5–9), Moderate Anxiety (10–14), and Severe Anxiety (15–21). The items are assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Never to 3 = Nearly every day), with a total score ranging from 0 to 21. A validity test of GAD-7 using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) showed a loading factor greater than or equal to 0.60, and the reliability test with Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.91 demonstrated excellent internal consistency. To ensure cultural relevance, the GAD - 7 instrument used has been validated in the Indonesian context [14].

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of both instruments into Bahasa Indonesia were performed by the research team, composed of experts in psychiatric nursing, midwifery, and community nursing, all of whom are fluent in both English and Bahasa Indonesia. The translation followed a forward and backward translation process to ensure linguistic accuracy and cultural relevance. The pre-final versions were tested on 10 participants during a pilot phase to assess clarity, cultural appropriateness, and understanding, followed by minor linguistic adjustments where necessary.

To ensure the clarity and comprehensibility of the final versions, written instructions were provided to participants, and the operator was available to explain any unclear items during administration. This adaptation process ensured that the instruments remained valid and culturally appropriate for use in the Indonesian context.

Data Analysis

This study assessed adolescent anxiety levels using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and maternal prenatal stress using the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ). Data analysis, performed with SPSS (version 26), included descriptive statistics to characterize respondents and examine mean values, standard deviations, and data distribution. A normality test using Kolmogorov-Smirnov showed

p < 0.0001 (p < 0.05), indicating that the data were not normally distributed. Therefore, the relationship between maternal stress during pregnancy and adolescent anxiety was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation test, which is suitable for ordinal-scaled data that are not normally distributed. Additionally, to determine the influence of prenatal stress on adolescent anxiety levels, ordinal regression analysis was employed, considering that the dependent variable (adolescent anxiety level) was ordinal. Ordinal regression was used to assess the extent to which an increase in maternal prenatal stress levels contributed to a higher likelihood of adolescent anxiety. All analyses were conducted with a significance level of p < 0.05, indicating that the results obtained were statistically meaningful.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ref: 2025-014). Participants provided written informed consent, and data confidentiality was ensured. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), and data were stored securely with password-protected files.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

All mothers were under 20 years old during pregnancy (100%). Most mothers had dropped out of school or did not continue their education beyond elementary or junior high school (74.1%). The majority of mothers were housewives (63.6%) and married (86%), while single mothers were those who had experienced divorce after giving birth. Most mothers were experiencing their first pregnancy (50.3%), while those with a second or subsequent pregnancy had a history of previous miscarriage. The majority of mothers experienced mild pregnancy complications (81.1%), such as mild anemia, excessive nausea and vomiting, or low blood pressure, while the remaining mothers experienced severe complications (18.9%). Most children of mothers who experienced stress during pregnancy have now reached adolescence, with the majority aged 10-13 years (51.0%) and currently attending junior high school (73.4%). The majority of the children were male (52.4%). Most respondent families belonged to the lower socioeconomic status category (51.0%), and the majority of the children lived in urban areas (51.0%).

During pregnancy, the majority of mothers (91.6%) experienced moderate levels of stress, while a small proportion experienced low (2.1%) or high (7.0%) stress levels, as measured by the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ). Among adolescents, 2.7% reported mild anxiety, 88.1% moderate anxiety, and 9.8% severe anxiety, as measured by the GAD-7.

A majority of mothers reporting high stress levels also came from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which may reflect the compounding effect of economic hardship on prenatal stress.

Table 1 presents the demographic data of respondents.

|

Characteristic |

Category |

n (%) |

M (SD) |

Median (IQR) |

|

Sociodemographic of Mother |

||||

|

Age at pregnancy |

13 – 19 |

15.91(2.02) |

15.91 (14.55–17.27) |

|

|

Education |

Elementary / Junior High School |

106 (74.1%) |

||

|

High School / Vocational High School |

37 (25.9%) |

|||

|

Occupation |

Housewife |

91 (63.6%) |

||

|

Fulltime |

28 (19.6%) |

|||

|

Part – time |

11 (7.7%) |

|||

|

Self – employed |

13 (9.1) |

|||

|

Marital Status |

Married |

123 (86%) |

||

|

Single Parent |

20 (14%) |

|||

|

Number of Children |

First child |

72 (50.3%) |

||

|

Second child or more |

67 (46.9%) |

|||

|

Twins |

4 (2.8) |

|||

|

History of pregnancy complication |

Mild |

116 (81.1) |

||

|

Severe |

27 (18.9) |

|||

|

Sociodemographic of Teenage |

||||

|

Adolescent age |

12 – 18 |

14.04 (1.89) |

14.04 (12.77–15.31) |

|

|

Adolescent gender |

Male |

75 (52.4%) |

||

|

Female |

68 (47.6%) |

|||

|

Education Level |

Junior High School |

105 (73.4%) |

||

|

Senior High School |

38 (26.6%) |

|||

|

Family Socioeconomic status |

Low |

73 (51%) |

||

|

Middle |

70 (49%) |

|||

|

Residence Environment |

Urban |

73 (51%) |

||

|

Rural |

70 (49%) |

|||

|

Maternal stress levels during pregnancy |

Low |

2(1.4%) |

||

|

Middle |

131(91.6%) |

|||

|

High |

10(7%) |

|||

|

Anxiety levels in adolescents |

Mild |

3 (2.1%) |

||

|

Moderate |

126 (88.1%) |

|||

|

Severe |

14 (9.8%) |

|||

Table 1. Sociodemographic, maternal stress levels during pregnancy and adolescent anxiety levels (n = 143)

Relationship Between Maternal Stress During Pregnancy and Adolescent Anxiety Levels

The Spearman test results indicate a positive and significant relationship between maternal stress during pregnancy and adolescent anxiety levels, with a correlation coefficient of 0.51 and a significance value of 0.005 (Table 2).

|

Mean (SD) |

Median (IRQ) |

Sig. (2 tailed) Spearman Correlation |

|

|

Maternal stress levels during pregnancy |

35.82 (4.51) |

35.82 (32.76–38.88) |

Correlation coefficient of 0.512 and significance value (p) of 0.005* |

|

Anxiety levels in adolescents |

12.55 (2.43) |

12.55 (10.91–14.19) |

*p < 0.05, SD = standard deviation, IRQ = interquartile range [Q1, Q3]

Table 2. Relationship Between Maternal Stress Levels During Pregnancy and Adolescent Anxiety Levels

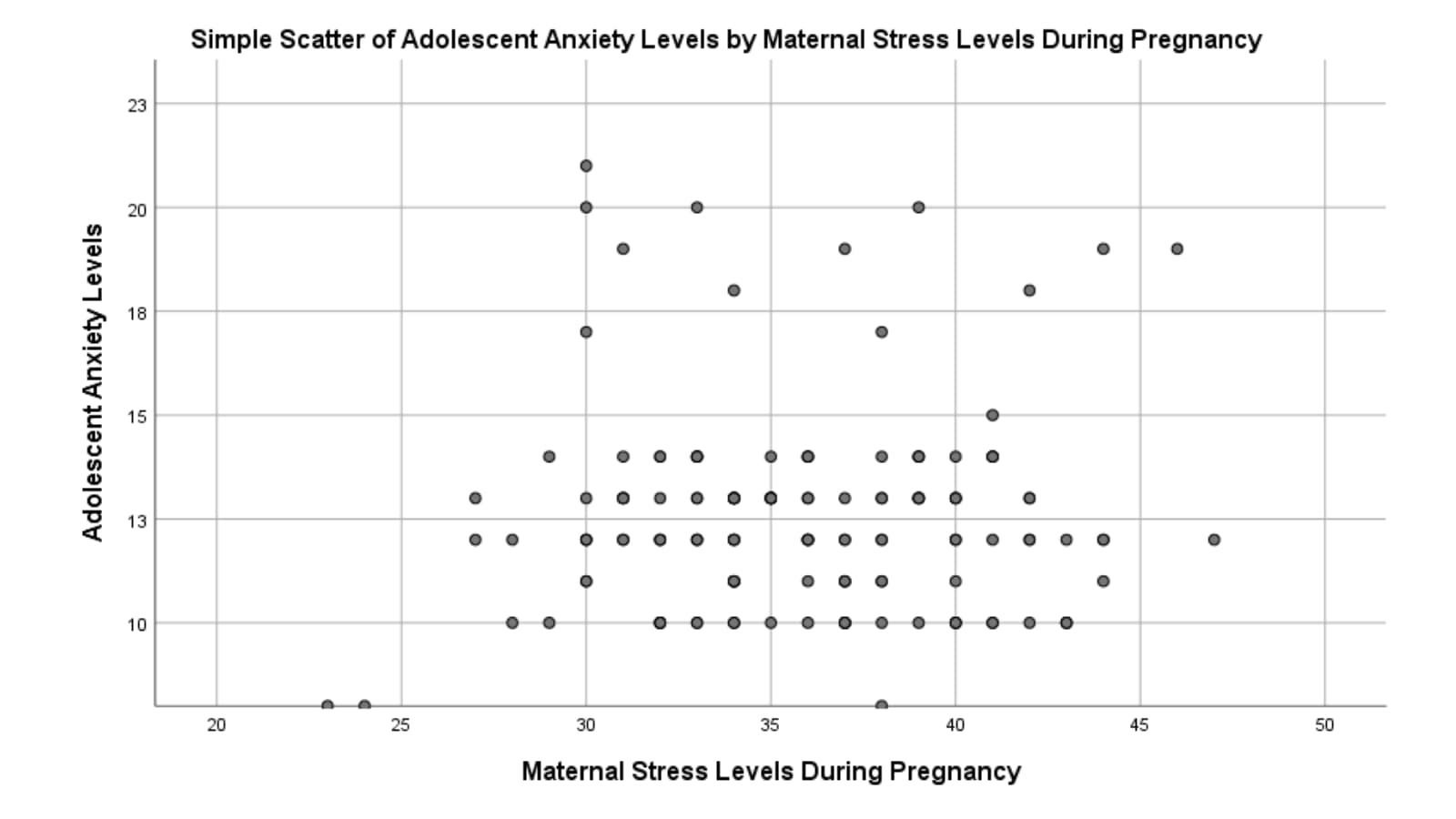

Figure 1 presents a scatter plot showing a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.51) between prenatal stress and adolescent anxiety. This correlation suggests that higher maternal stress levels during pregnancy are associated with increased adolescent anxiety levels. The results also indicate that the relationship between these two variables is moderate to strong and remains statistically significant.

Figure 1 Scatter Plot of Adolescent Anxiety Levels by Maternal Stress Levels During Pregnancy

The crosstabulation table shows the distribution of respondents based on maternal stress levels during pregnancy and adolescent anxiety levels. The majority of adolescents with moderate anxiety levels came from mothers with moderate stress levels (Middle), totaling 118 out of 131 individuals. Among mothers with high stress levels (High), the distribution of adolescent anxiety varied more, with 8 adolescents experiencing moderate anxiety and 2 experiencing severe anxiety (Table 3).

|

Maternal stress levels during pregnancy |

Anxiety levels in adolescents |

Total |

||

|

Mild |

Moderete |

Severe |

||

|

Low |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Middle |

1 |

118 |

12 |

131 |

|

High |

0 |

8 |

2 |

10 |

|

Total |

3 |

126 |

14 |

143 |

Table 3. Crosstabulation of Maternal stress levels during pregnancy and Anxiety levels in adolescents

The Effect of Prenatal Stress on Adolescent Anxiety Levels

The ordinal regression analysis results indicate that the overall model is significant, with a Chi-Square value of 27.894 and p < 0.05, meaning that maternal stress during pregnancy significantly affects adolescent anxiety levels. The Nagelkerke R²value of 0.456 suggests that the model explains 45.6% of the variability in adolescent anxiety levels, indicating a moderate to strong relationship.

The model fit test shows that the Pearson value and Deviance value are both greater than 0.05, indicating a good model fit with the data. The parameter estimation results show that the threshold for category 2 (-3.876, p < 0.0001) is significant, meaning that higher maternal stress during pregnancy increases the likelihood of higher adolescent anxiety levels. Additionally, the variable of maternal stress during pregnancy (1.562, p < 0.0001) is also significant, confirming a direct and significant effect of maternal stress during pregnancy on adolescent anxiety levels.

In Table 4 we reported the results of the Ordinal Regression test.

|

Table 4a. Model Summary for Ordinal Regression |

|||||||||||

|

Model Component |

Value |

df |

Sig. (p-value) |

||||||||

|

Model Fit (Chi-Square) |

27.894 |

2 |

<0.0001 ** |

||||||||

|

Pearson Goodness-of-Fit |

χ² = 4.216 |

– |

0.081 |

||||||||

|

Deviance Goodness-of-Fit |

χ² = 5.678 |

– |

0.067 |

||||||||

|

Nagelkerke R² |

0.456 |

– |

– |

||||||||

|

Table 4b. Parameter Estimates for Predictors of Adolescent Anxiet |

|||||||||||

|

Variable / Threshold |

B |

SE |

Wald χ² |

df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

95% CI for Exp(B) |

||||

|

Threshold [Moderate Anxiety] |

–3.876 |

1.102 |

12.39 |

1 |

0.001 ** |

– |

– |

||||

|

Maternal Stress During Pregnancy |

1.562 |

0.496 |

9.91 |

1 |

0.002 ** |

4.77 |

1.60 – 5.05 |

||||

|

Threshold: cutoff value between anxiety categories. ** indicates significant contribution to the model. |

|||||||||||

Table 4. Results of Ordinal Regression Analysis

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that prenatal stress has a significant relationship with adolescent anxiety, aligning with the nature vs. nurture debate in child psychological development [15]. The nature factor influences children's predisposition to anxiety through genetic inheritance from parents, while the nurture factor shapes children's emotional development through environmental influences during pregnancy, including maternal stress [16]. According to a study by Van Den Bergh et al., (2005), stress experienced by the mother during pregnancy might change the responses of the fetal neurological system, especially in the limbic system, which is essential for controlling emotions [4]. Changes in the limbic system make children exposed to prenatal stress more susceptible to anxiety during adolescence [17]. Our findings are consistent with Rogers et al. (2020), who found a strong association between maternal perinatal mental health and long-term emotional outcomes in children [18].

The sociodemographic characteristics of mothers in this study reinforce the connection between nature and nurture in adolescent anxiety development. Young maternal age, low education levels, and economic pressure increase stress during pregnancy, which subsequently affects child development. Genetic factors may contribute to the inheritance of anxiety tendencies, which are then exacerbated by environmental stress [19]. A study by Sebők-Welker et al., (2024) found that mothers with low education levels have limited stress management skills, worsening the impact of prenatal stress on their children [20]. This further highlights the significant role of the prenatal environment in children's mental health.

Social and economic support plays a crucial role in clarifying the interaction between nature and nurture in adolescent anxiety development. Some children may have a more sensitive stress response system due to genetic factors, making them more vulnerable to anxiety. A supportive social environment can help mitigate the negative effects of genetic predisposition and prenatal stress [21]. According to a study by Nóblega et al., (2024), mothers from low socioeconomic backgrounds who endure prenatal stress likely to have a greater negative effect on the emotional development of their children [22]. The majority of children in this study lived in urban areas, which, according to Raman et al., (2021), is associated with higher exposure to environmental stressors such as academic and social pressures, further exacerbating their anxiety [23].

The findings of this study support the theory that the interaction between biological (nature) and environmental (nurture) factors significantly determines adolescent anxiety development. A study by Jensen, (2025) found that children whose mothers experienced prenatal stress were more likely to develop anxiety, particularly if they also had a family history of anxiety disorders [24]. Genetic factors provide an initial vulnerability to anxiety, but environmental experiences during pregnancy and childhood determine whether this predisposition develops into a more severe psychological disorder. The findings indicate that maternal stress during pregnancy is not just an individual issue but also contributes to children's future psychological well-being.

However, this study has several limitations. This study did not control for postnatal maternal anxiety or childhood trauma, which may also influence adolescent outcomes. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling may limit external validity. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. Future research should address these limitations. Longitudinal studies are essential to establish causal links and to examine whether prenatal stress directly leads to persistent anxiety symptoms across developmental stages. Such research could offer deeper insight into the mechanisms linking prenatal conditions to long-term mental health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The use of purposive sampling facilitated the selection of respondents who could recall and describe their pregnancy experiences; however, it limits the generalizability of the findings, as the sample may not represent the broader population of mothers with adolescent children. This method also increases the risk of selection bias, as those who agreed to participate may have had particularly strong emotional experiences, potentially influencing the results. Future studies are recommended to use random or stratified sampling to enhance external validity. Additionally, the data relied on maternal recall of prenatal stress without objective verification such as medical records. This introduces the potential for recall bias, especially considering the time elapsed since pregnancy. Although participants were screened for major psychiatric disorders, no specific assessment of memory reliability was conducted. To address this, future research should consider prospective designs or data triangulation. The study was also limited to a specific geographic and cultural context, which may affect the applicability of the findings to populations with different sociocultural backgrounds. Lastly, the use of self-report measures introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, where participants may adjust their responses to align with perceived expectations.

CONCLUSION

According to this study, teenage anxiety levels are substantially correlated with maternal stress during pregnancy. These findings reinforce previous research suggesting that prenatal stress can influence children's emotional development through neuroendocrine responses and psychosocial factors. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents, such as young maternal age, low education levels, and unfavorable socioeconomic status, contribute to high stress levels during pregnancy, ultimately affecting children's anxiety in adolescence. The study's findings highlight the long-term effects of maternal psychological states during pregnancy on the emotional health of offspring. These findings suggest that early interventions aimed at reducing maternal stress during pregnancy may play a key role in preventing anxiety disorders and promoting long-term mental health in children.

Research Ethics and Conflict of Interest

This study was approved by the Institute of Science and Health Technology Insan Cendekia Medika Jombang's Research Ethics Committee (reference number 2025-014) on January 15, 2025. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

We extend our deepest gratitude to the mothers who sincerely recalled their pregnancy experiences and to the adolescents who were willing to share their stories and participate in this research. Without their openness, patience, and participation, this study would not have been possible.

Author Contributions

Concept and study design, manuscript writing and critical manuscript revision: DE, NAA, EPY, EY; data analysis and interpretation: DE, NAA. Final approval before publication: DE, NAA, EPY, EY.

REFERENCES

[1] Chauhan A, Potdar J. Maternal Mental Health During Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Cureus 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30656.

[2] Graham AM, Doyle O, Tilden EL, Sullivan EL, Gustafsson HC, Marr M, et al. Effects of maternal psychological stress during pregnancy on offspring brain development: Considering the role of inflammation and potential for preventive intervention. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2021;7:461. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BPSC.2021.10.012.

[3] Wu Y, De Asis-Cruz J, Limperopoulos C. Brain structural and functional outcomes in the offspring of women experiencing psychological distress during pregnancy. Mol Psychiatry 2024 297 2024;29:2223–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02449-0.

[4] Van Den Bergh BRH, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29:237–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007.

[5] Jagtap A, Jagtap B, Jagtap R, Lamture Y, Gomase K. Effects of Prenatal Stress on Behavior, Cognition, and Psychopathology: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.47044.

[6] Pascal R, Casas I, Genero M, Nakaki A, Youssef L, Larroya M, et al. Maternal Stress, Anxiety, Well-Being, and Sleep Quality in Pregnant Women throughout Gestation. J Clin Med 2023;12:7333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12237333.

[7] Zhang L, Huang R, Lei J, Liu Y, Liu D. Factors associated with stress among pregnant women with a second child in Hunan province under China’s two-child policy: a mixed-method study. BMC Psychiatry 2024;24:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05604-7.

[8] Karnwal R, Sharmila K. Perspective View of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Pregnant Women: A Review. J Ecophysiol Occup Heal 2024;24:7–19. https://doi.org/10.18311/jeoh/2024/35771.

[9] Awad-Sirhan N, Simó-Teufel S, Molina-Muñoz Y, Cajiao-Nieto J, Izquierdo-Puchol MT. Factors associated with prenatal stress and anxiety in pregnant women during COVID-19 in Spain. Enferm Clin 2022;32:S5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2021.10.006.

[10] Morales-Munoz I, Ashdown-Doel B, Beazley E, Carr C, Preece C, Marwaha S. Maternal postnatal depression and anxiety and the risk for mental health disorders in adolescent offspring: Findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2023;57:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674221082519.

[11] Tung I, Hipwell AE, Grosse P, Battaglia L, Cannova E, English G, et al. Prenatal Stress and Externalizing Behaviors in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol Bull 2023;150:107–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/BUL0000407,.

[12] Wardoyo H, Moeloek ND, Basrowi RW, Ekowati M, Samah K, Mustopo WI, et al. Mental Health Awareness and Promotion during the First 1000 Days of Life: An Expert Consensus. Healthc 2024;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12010044.

[13] Santoso JB. Pengembangan Skala Revised Prenatala Distress Questionnaire (NuPDQ) Versi Bahasa Indonesia. J Ilm Psikol MANASA 2018;7:62–71.

[14] Budikayanti A, Larasari A, Malik K, Syeban Z, Indrawati LA, Octaviana F. Screening of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Patients with Epilepsy: Using a Valid and Reliable Indonesian Version of Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Neurol Res Int 2019;2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5902610,.

[15] Shackman AJ, Gee DG. Maternal Perinatal Stress Associated With Offspring Negative Emotionality, But the Underlying Mechanisms Remain Elusive. Am J Psychiatry 2023;180:708–11. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20230630.

[16] Jami ES, Hammerschlag AR, Bartels M, Middeldorp CM. Parental characteristics and offspring mental health and related outcomes: a systematic review of genetically informative literature. Transl Psychiatry 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01300-2.

[17] Canini M, Pecco N, Caglioni M, KatušićA, Išasegi IŽ, Oprandi C, et al. Maternal anxiety-driven modulation of fetal limbic connectivity designs a backbone linking neonatal brain functional topology to socio-emotional development in early childhood. J Neurosci Res 2023;101:1484–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.25207.

[18] Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ, Rossen L, Spry EA, MacDonald JA, et al. Association between Maternal Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Child and Adolescent Development: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:1082–92. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2020.2910,.

[19] Lopez M, Ruiz MO, Rovnaghi CR, Tam GKY, Hiscox J, Gotlib IH, et al. The social ecology of childhood and early life adversity. Pediatr Res 2021;89:353–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01264-x.

[20] Sebők-Welker T, Posta E,Ágrez K, Rádosi A, Zubovics EA, Réthelyi MJ, et al. The Association Between Prenatal Maternal Stress and Adolescent Affective Outcomes is Mediated by Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Behavioral Inhibition System Sensitivity. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2024;55:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01499-9.

[21] Hasriantirisna H, Nanda KR, Munawwarah. M S. Effects of Stress During Pregnancy on Maternal and Fetal Health: A Systematic Review. Adv Healthc Res 2024;2:103–15. https://doi.org/10.60079/ahr.v2i2.339.

[22] Nóblega M, Retiz O, Nuñez del Prado J, Bartra R. Maternal Stress Mediates Association of Infant Socioemotional Development with Perinatal Mental Health in Socioeconomically Vulnerable Peruvian Settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024;21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070844.

[23] Raman TL, Aziz NAA, Yaakob SSN. The effects of different natural environment influences on health and psychological well-being of people: A case study in selangor. Sustain 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158597.

[24] Jensen P. From nature to nurture–How genes and environment interact to shape behaviour. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2025;285:106582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2025.106582.

CHALLENGES TO CANCER PATIENT ADVOCACY IN NURSING PRACTICE: A NARRATIVE REVIEW

Vincenza Giordano 1*, Assunta Guillari 2, Aniello Lanzuise 3, Rita Nocerino 2, Michele Virgolesi 1, Martina Micera 4, Teresa Rea 1

- Department of Public Health, University of Naples Federico II (NA)

- Department of Translational Medical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II (NA)

- Health Management, Colli Hospital (NA)

- Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital (RM)

* Corresponding author: Vincenza Giordano, Department of Public Health, University of Naples Federico II (NA). Email: enza-giordano@hotmail.it

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Advocacy by nurses caring for cancer patients is essential to ensure that their rights and wishes are respected throughout their care pathway. However, the ability of nurses to provide effective advocacy is limited by various organisational and managerial obstacles, potentially affecting the quality of care and patient well-being.

Objective: Description of the barriers to nursing advocacy in oncology, providing a critical summary of the available evidence to identify the main challenges and propose strategies for improvement.

Materials and Methods: A narrative review was conducted using databases such as PubMed, CINAHL and Cochrane Library between June and September 2024, using the Population, Intervention, Outcome (PIO) methodology.

Results: Four articles were deemed to be relevant to the study objective. The main issues that emerged from the narrative review were barriers to advocacy (lack of effective communication and work overload; fragmented continuity of care), improvement strategies (training and psychological support) and patients' experiences in the transition from distress to empowerment.

Conclusions: Various barriers hinder nursing advocacy in oncology, such as excessive workload, fragmentation of care and difficulties in addressing patients' emotional needs. This review underscores that the introduction of dedicated professionals, such as case managers, can provide organisational and coordinated support, helping to mitigate some of the barriers identified. Tackling the barriers to nursing advocacy is critical to ensuring high-quality, patient-centred cancer care. Strengthening organisational support, continuing education for nurses and the adoption of innovative care models are essential.

Keywords: Cancer patients, Neoplastic diseases, Nursing advocacy, Patient rights, Quality of life, Patient well-being, Patient healthcare.

INTRODUCTION

Nursing advocacy is defined as the active commitment of nurses to represent, protect and promote the rights, preferences and needs of patients, representing “the process through which nurses seek to protect the rights of patients, ensuring that their needs are met and that they receive safe, high-quality care” [1]. This involves a patient-centred approach, aimed at ensuring that patients receive high-quality care and that their decisions are respected within the healthcare system. Advocacy is based on communication skills, empathy and negotiation, as well as the ability to identify situations in which patients may be vulnerable or at risk of neglect [2]. In oncology, patients face complex and prolonged treatment pathways characterised by invasive treatment, debilitating side effects and significant emotional burden. Therefore, advocacy is particularly important for this type of patient, who requires a personalised approach and continuous support due to the changing nature of both the disease and its treatment [3]. Nurses are called upon to actively intervene to prevent patients from being subjected to injustice or neglect and to facilitate informed decision-making, an aspect that is essential to ensuring quality care. Nursing advocacy is not merely clinical support; it is an approach rooted in empathy, communication and the ability to negotiate solutions that respect the dignity and wishes of the patient. This includes support throughout the entire patient care process [2]. However, despite the recognised importance of this aspect, barriers to nursing advocacy remain widespread, including organisational pressure, lack of time and the weight of the doctor-nurse hierarchy. These factors limit the ability of nurses to provide continuous, personalised support [4].

Oncology is a complex field, and these challenges are even tougher because of the need to coordinate multidisciplinary care, which involves doctors, specialists, social workers, and psychologists. This complexity demands a high level of coordination and effective interprofessional communication, which isn't always achieved in the best way. The fragmentation of roles and responsibilities can create difficulties in information sharing and planning care, increasing the risk of problems that could compromise the patient's treatment pathway [4]. On top of that, the emotional strain of caring for cancer patients in the later stages of the disease, combined with the need to provide psychological support to patients and their families, makes it hard to balance defending patients' rights and managing professional stress [5].

Several studies [2,6] have explored nursing advocacy in a variety of clinical settings, demonstrating that it is essential for promoting a holistic approach that includes patient education, interprofessional communication and psychological support. While the importance of this topic is widely recognised, there are no specific systematic reviews describing the barriers to fully understanding nursing advocacy in oncology. This narrative review therefore aims to bridge this gap by providing a detailed overview of the barriers that limit nursing advocacy in oncology. The identification and description of these needs is essential for developing targeted strategies that improve the effectiveness of nursing care, with consequent benefits for the quality of care and the well-being of cancer patients.

Objective

To describe the barriers that hinder nursing advocacy in the oncology sector, providing a critical summary of the available evidence to identify the main challenges and suggest possible strategies for improvement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This narrative review was conducted in accordance with guidelines for the preparation of narrative reviews for peer-reviewed journals [7-9].

Study design

The research aims to answer the following question, formulated according to the Population, Intervention, Outcome (PIO) methodology: “What are the barriers that limit nursing advocacy for cancer patients, and how do they affect the quality of care and patient well-being?”

The PIO sets out the population to be analysed, the measures to be taken and the outcomes (Table 1).

|

P |

Cancer Patients |

|

I |

Barriers to nursing advocacy |

|

O |

Quality of patient care and well-being |

Table 1. Query according to the PIO method.

Research strategy

The study was conducted using various scientific databases, consulted between June 2024 and September 2024. The databases chosen for this work include PubMed, CINAHL, APA PsycArticles, and APA PsycInfo. During the research phase, specific keywords were used to narrow down the field of research and identify the most relevant studies, thus optimising the review process. The keywords used for the various searches were: "Cancer", "Barriers to advocacy", "Quality of Care", "Patient well-being". For each Medical Subject Headings term (MeSH), possible synonyms were identified. The keywords, together with their synonyms, have been combined using Boolean operators "AND" and "OR" to optimise the search and narrow down the most relevant results.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

During the first phase of research and selection of studies, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. The following were included: (a) quantitative and qualitative primary studies; (b) studies investigating barriers that limit nursing advocacy for cancer patients and affect the quality of care and well-being of cancer patients; (c) articles in Italian and English language. The following were excluded: (a) secondary studies, reviews, meta-analyses or meta-syntheses; (b) studies investigating the barriers that limit nursing advocacy and affect the quality of care and well-being of non-cancer patients.

RESULTS

The survey produced a total of 542 articles, of which 536 came from databases (249 from PubMed, 218 from CINAHL and 69 from APA PsycArticles and APA PsycInfo) and 6 articles from free research. Finally, four articles were included in the review: one qualitative study, one RCT, and two cohort studies. The extraction and summary of the articles is shown in Table 2.

|

Author and type of study |

Population |

Study objective |

Results |

|

Horner et al., 2012 Randomised Controlled Trial |

N= 251 patients (intervention group exposed to the nursing navigator: n=133 patients with lung, breast and colorectal cancer |

Investigate the impact of an oncology nursing navigation programme on closing the care gap |

Patients who received support from the oncology nurse navigator rated the quality of care and continuity of care as better than those without a navigator, with fewer gaps in the care pathway. |

|

Reiser et al., 2021 Prospective cohort study |

n= 118 women with metastatic breast cancer |

Explore the impact of a nursing project to enhance coordination of supportive care in women with MBC, identifying barriers to advocacy. |

The programme demonstrated that targeted nursing assessment can overcome barriers, improve symptom management and reduce anxiety through nursing advocacy. |

|

Fillion et al., 2006 Observational cohort study |

n=158 patients with head and neck tumours (cohort exposed to professional navigators (n=83) and a historical cohort (n=75). |

Assess the impact of a case manager on the continuity of care and empowerment of cancer patients, identifying barriers that restrict access to support services and patient care. |

The navigator cohort reported better continuity of care, fewer cancer-related problems and improved quality of emotional life, highlighting the role of the navigator in overcoming barriers and supporting patient advocacy. |

|

Chan et al., Qualitative study |

n= 93 (47 women; 46 men) |

Exploring patients' perceptions of nurse-patient communication and barriers to psychosocial care in the oncology setting. |

The main barriers include high workloads and insufficient time, which hinder psychosocial support and continuity of care. |

Table 2. Data extraction

The studies selected were conducted in several countries, including Hong Kong, Canada, western Pennsylvania, and Washington. All in all, these studies involved 620 cancer patients. In qualitative studies, the average age of participants ranged from 58 years for women with metastatic breast cancer to 60-70 years for men with prostate cancer undergoing radical treatment. In quantitative studies, which included cancer patients hospitalised in hospital wards and patients with head and neck cancer, the average age of participants was between 55 and 63 years.

The main issues that emerged were barriers to advocacy (lack of effective communication and excessive workload; fragmentation of continuity of care), strategies for improvement (education and psychological support) and patients' experiences of moving from distress to empowerment.

Barriers to advocacy

Nursing advocacy is an essential component of cancer patient care, providing not only clinical support, but also emotional and informational guidance. However, a number of factors hinder the full exercise of this function, compromising the quality of care and the overall patient experience. Through analysis of the literature, several themes emerged: lack of effective communication and excessive workload, fragmentation of continuity of care, improvement strategies, education and psychological support, and patients' experiences as they move from distress to empowerment.

The themes were identified through a topical analysis of the studies included in the narrative review, which made it possible to identify recurring conceptual categories by comparing the responses and results of the studies. These were then grouped into main categories, representing the key areas of concern and the proposed strategies.

Lack of Effective Communication and Work Overload

Communication between nurses and patients is a key element of advocacy, but it can be compromised by organisational and management factors. The qualitative study by Chan et al. (2018) [3] highlighted how excessive workloads and fragmented care management pose significant obstacles, with direct repercussions on patient perception. The interviews conducted revealed a general reluctance to approach nurses for non-urgent issues, as they were seen as being too busy: "The nurses are just too busy... they don't have time to talk to patients". This results in limited opportunities to address psychological and emotional needs, as highlighted by another patient: "I don't talk to the nurses about my concerns... it's not their job to help me with psychological problems" [3]. This scenario points to a vicious circle in which a lack of time and resources hampers the building of a trusted relationship, which is essential to ensuring patient-centred care.

Fragmentation of Continuity of Care

A significant additional obstacle is the fragmentation of continuity of care. Horner et al. (2013) [10] noted an average delay of 42.93 days between diagnosis and the start of treatment in patients without a nursing reference point, demonstrating how the absence of a dedicated figure can negatively influence the clinical pathway. Furthermore, the absence of coordination led to a 30% increase in missed appointments, reflecting organisational difficulties that impact on patients' ability to adhere to treatment.

Improvement Strategies

Confronted with these barriers, a number of strategies have been developed to enhance nursing advocacy and improve the patient experience.

The development of Nursing Navigation Programmes is one of the first strategies. Studies such as those by Fillion et al. (2009) [11] and Horner et al. (2013) [10] have explored the role of specialised figures, such as the Professional Navigator (PNO) and the Oncology Nursing Navigator (ONN), in coordinating and managing care.

Il Professional Navigator (PNO), supports patients throughout their cancer journey, ensuring continuity of care and reducing logistical barriers. The study by Fillion et al. (2009) [11] highlighted how PNO significantly improves the organisation of care, with a 25% reduction in hospital admissions and a positive impact on quality of life: 60% of patients supported by PNO reported a reduction in anxiety, compared to 48% of the historical cohort.

At the same time, the Oncology Nursing Navigator (ONN), with a particular focus on oncology nursing care, has shown a significant impact in reducing delays in treatment (from 42.93 to 15.15 days) and improving treatment compliance (Horner et al., 2013) [10]. The presence of an ONN allowed for a reduction in missed appointments and guaranteed constant patient support, limiting the risk of interruptions in treatment.

Education and Psychological Support

As well as coordinating care, psychological support and health education are key to boosting patients' confidence in their treatment. Reiser et al. (2019) [6] have developed a nursing education programme specifically for women with metastatic breast cancer, demonstrating how targeted support can reduce feelings of isolation (42% of participants) and improve their quality of life.

Patient experiences moving from Discomfort to Empowerment

Patient experiences clearly reflect the important role of effective advocacy. Chan et al. (2018) [3] found that physical treatments are also perceived as a form of psychological comfort: "The fact that the nurse takes care of my physical pain makes me feel better mentally as well". However, the lack of structured emotional support has meant that many patients have lowered their expectations when it comes to discussing their psychological needs with nursing staff. Furthermore, studies such as those by Fillion et al. (2009) [11] and Reiser et al. (2019) [6] have demonstrated that integrating navigation programmes and nursing support can enhance patient empowerment, helping them make more informed decisions and improving compliance with treatment.

Study assessment

The quality of the narrative review was assessed using the SANRA Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) (Table 3), a validated method for making sure narrative reviews are methodologically sound [12].

|

First Author, year |

Justification of the article's significance for readers |

Statement of clear objectives or formulation of questions |

Description of Literature Research |

Referencing |

Scientific Reasoning |

Appropriate data presentation |

Score |

|

Hornet et al., 2012 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

Reiser et al., 2021 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

Fillion et al., 2006 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

Chan et al., 2018 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

|

Note: The six items that make up the scale are assessed using whole numbers from 0 (low score) to 2 (high score), with 1 as the midpoint. The maximum score for the overall sum is 12 |

|||||||

Table 3. SANRA Scale

An analysis of the selected articles highlights a moderate variability in the methodological quality of the narrative reviews. The overall scores range from a minimum of 8 to a maximum of 11 out of 12, suggesting an overall good level, but with room for improvement in some key areas.

In particular, the articles by Reiser et al. (2021) [6] and Fillion et al. (2006) [11] obtained the highest score (11/12), demonstrating good methodological consistency. Both clearly set out the importance of the topic, outline specific objectives and demonstrate sound scientific reasoning, although the description of the literature review remains limited (score 1), indicating a possible lack of transparency in the criteria for selecting sources. Horner et al. (2012) [10] display a similar profile but with a slightly lower score (10/12), penalised by a less convincing initial justification of the article's importance (score 1), suggesting that the article may not have clearly explained its added value for the reader. The article with the lowest score is that of Chan et al. (2018) (8/12) [3], which stands out negatively for its lack of well-defined objectives and weak scientific reasoning (scores of 1). Despite its good presentation of data (score 2), the article appears to suffer from poor methodological structure and limited description of the literature consulted, which are fundamental elements for the rigour of a narrative review. Assessment using the SANRA scale [12] reveals variability in the quality of the studies included, with some articles characterised by a more robust methodological structure and others by significant shortcomings. The strength of the conclusions depends on this diversity: studies with higher scores provide a more reliable basis, while those with lower scores should be interpreted with caution. Therefore, the final conclusions of the review must be interpreted taking into account the overall methodological quality, which represents a potential limit to the generalisability of the results.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to describe the barriers that hinder nursing advocacy in the oncology context, providing a critical summary of the available evidence to identify the main challenges and propose possible strategies for improvement.

This narrative review has revealed that nursing advocacy in oncology is impeded by a series of barriers that overlap between individual, organisational and systemic dimensions. These include a lack of effective communication and excessive workloads, which have emerged as cross-cutting obstacles limiting nurses' ability to provide appropriate emotional support and establish empathetic relationships with patients [3-4]. These critical issues have a negative impact on the perception of patients, who see nurses as too busy to address their psychological needs, thus compromising the relationship of trust. Berben et al. [14] confirm this evidence, emphasising how complex nursing interventions focused on quality of life can improve perceived well-being and communication.

The fragmented nature of continuity of care is another significant obstacle. Horner et al. (2013) [14] highlight delays in treatment and difficulty in adhering to therapy when there is no regular nursing reference point. Tomaschewski-Barlem et al. (2017) [13] confirm this finding, suggesting that work environments that promote professional autonomy and collaboration between different professions facilitate better continuity of care.

Among strategies for improvement, the introduction of specialised professionals such as Professional Navigators (PNO) and Oncology Nurse Navigators (ONN) has proven useful in reducing fragmentation of care and providing significant emotional and psychological support [11,12,17,18], confirming the importance of holistic support offered by experienced professionals who are able to address not only clinical aspects, but also relational and social aspects. Likewise, Pautasso et al. (2018) [19] and McMullen et al. (2013) [20] document real benefits in terms of symptom management, care coordination, and psychological well-being.

Guided consultations by experienced nurses are another promising strategy. Drach-Zahavy et al. [15] and Grassi et al. [16] demonstrate that these approaches improve continuity of care, psycho-emotional management and patient satisfaction, underscoring the key role of nurses in the multidisciplinary team.

The experience of cancer patients, from discomfort to empowerment, stands out as a central theme. Chan et al. (2018) [3] observe that patients also see physical care as psychological comfort, but the lack of space for discussion about emotional issues can lead to isolation. Nursing navigation programmes [6,11] demonstrate that active patient involvement encourages empowerment and improves treatment adherence. The lack of specific training in advocacy is a well-documented cross-cutting barrier [21-24], and the integration of dedicated training in nursing curricula is a priority.

As a whole, the comparison with external studies complements and validates the findings, highlighting critical issues and suggesting practical solutions. The introduction of specialised figures, the enhancement of nurse training and the promotion of collaborative environments emerge as key interventions to make nursing advocacy more effective and focused on the needs of cancer patients.

Limitations and strong points

This review brings to light both significant aspects that offer opportunities for improvement and critical issues that limit its full implementation. One of the strengths that emerged is the clear identification of multidimensional barriers that include psychological, social, management and institutional aspects. A wide range of databases were included in the search, such as PubMed, CINAHL, APA PsycArticles and APA PsycInfo, ensuring broad coverage of relevant sources. This interdisciplinary approach has been beneficial in providing a comprehensive insight into the topic. Moreover, the combination of qualitative and quantitative studies allowed for the integration of experiential perspectives with measurable data, enriching the overall understanding of the challenges related to nursing advocacy. Another strong point is the focus on oncology, which is a complex field in which nursing advocacy plays a crucial role in improving the quality of care and the lives of patients. Furthermore, the review highlighted applicable operational solutions, such as the introduction of specialised roles (e.g. case managers) and proactive support programmes, which demonstrate the potential to address management barriers and improve overall care. Nevertheless, the review has some limitations. Although the narrative review method offers a broad and flexible overview, it can introduce bias in the selection and interpretation of studies, thereby limiting the generalisability of the results. A further limitation is the small number of studies included and the heterogeneity of the healthcare contexts, making it difficult to apply the findings uniformly to different healthcare systems, including the Italian one.

Finally, this narrative review was based mainly on articles published in peer-reviewed journals, excluding grey literature (e.g., theses, conference proceedings and technical reports). However, it is acknowledged that grey literature could offer further insights into barriers to nursing advocacy, in particular in settings that are less documented in the academic literature. Future studies may integrate these elements to provide a more comprehensive view of the phenomenon.

Implications for clinical practice

The implications drawn from the literature review point to the need to systematically address the barriers that limit the efficacy of nursing advocacy in the oncology setting. The most significant barriers identified include excessive workloads, fragmented continuity of care and a lack of psychological and educational support, all of which have a negative impact on the quality of care and patient well-being.

An initial priority is to improve organisational and working conditions for nursing personnel. Strategies that provide for a more even redistribution of the workload and the enhancement of human resources can mean that nurses are able to devote time to providing emotional and psychological support to patients, thereby overcoming the perception that their role is limited to physical care alone, as highlighted in the study by Chan et al. (2018) [3].

A second crucial aspect is the adoption of innovative, patient-centred care models, such as the introduction of dedicated professionals, such as the Professional Navigator and the Oncology Nurse Navigator, described in the studies by Fillion et al. (2009) [11] and Horner et al. (2013) [10]. In facilitating coordination between patients and multidisciplinary teams, these professionals are better able to improve continuity of care and reduce organisational gaps that often hinder advocacy. For example, the provision of a nursing navigator has been shown to reduce the time between diagnosis and the start of treatment and to improve treatment compliance, while providing greater emotional and psychological support for cancer patients.

Last but not least, investment in continuing education for nurses is a key step towards empowering them in their role as advocates. Training should be focused on advanced communication skills and managing the complex emotional needs of cancer patients, as recommended by the study by Reiser et al. (2019) [6]. These training initiatives not only improve the quality of care, but also increase patient confidence in the treatment process, helping to improve their quality of life.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this narrative review highlights the complex and multidimensional nature of the barriers that stand in the way of nursing advocacy in oncology. The evidence collected reveals how organisational, managerial and psychological elements limit the ability of nurses to fully establish themselves as defenders of patients' rights. Recognising these critical issues clears the way for targeted action, in particular through the adoption of specialised roles – such as Nurse Navigator and Professional Navigator – and specific training, enabling more effective coordination and consolidating advocacy practices. Furthermore, consideration of socio-cultural factors emerges as an essential factor in developing intervention strategies that are increasingly in line with the reality of different care contexts. Addressing these barriers systematically is, therefore, a fundamental step towards a model of care that integrates and enhances the role of nurses as advocates, helping to make cancer care more cohesive and focused on patients' needs.

Funding statement

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

All Authors equally contributed.

REFERENCES

- Bu X, Jezewski MA. Developing a mid-range theory of patient advocacy through concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2007 Jan;57(1):101-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04096.x.

- Vaartio H, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S, Suominen T. Nursing advocacy: how is it defined by patients and nurses, what does it involve and how is it experienced? Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(3):282-292. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00406.x

- Chan EA, Wong F, Cheung MY, Lam W. Patients' perceptions of their experiences with nurse-patient communication in oncology settings: A focused ethnographic study. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199183

- Negarandeh R, Oskouie F, Ahmadi F, Nikravesh M, Hallberg IR. Patient advocacy: barriers and facilitators. BMC Nurs. 2006;5:3. doi:10.1186/1472-6955-5-3

- Granek L, Nakash O, Ariad S, Shapira S, Ben-David M. Mental health distress: oncology nurses’ strategies and barriers in identifying distress in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(1):43–51. doi: 10.1188/19.CJON.43-51

- Reiser V, Rosenzweig M, Welsh A, Ren D, Usher B. The Support, Education, and Advocacy (SEA) Program of Care for Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Nurse-Led Palliative Care Demonstration Program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019 Oct;36(10):864-870. doi: 10.1177/1049909119839696

- Silva, A.R., Padilha, M.I., Petry, S., Silva, E., Silva, V., Woo, K., Galica, J., Wilson, R., & Luctkar-Flude, M. (2022). Reviews of Literature in Nursing Research: Methodological Considerations and Defining Characteristics. Advances in Nursing Science, 45(3), 197-208. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000418.

- Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, & Malterud K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 48, e12931. doi:10.1111/eci.12931.

- Aveyard H, & Bradbury-Jones C. (2019). An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: Findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 105. doi:10.1186/s12874-019-0751-7.

- Horner K, Ludman EJ, McCorkle R, Canfield E, Flaherty L, Min J, et al. An oncology nurse navigator program designed to eliminate gaps in early cancer care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013 Feb;17(1):43-48. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.43-48. PMID: 23372095

- Fillion L, de Serres M, Cook S, Goupil RL, Bairati I, Doll R. Professional patient navigation in head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25(3):212-221. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.001.

- Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. The SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4:5. doi: 10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8

- Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, Lunardi VL, Barlem ELD, Silveira RSD, Ramos AM, Piexak DR. Patient advocacy in nursing: barriers, facilitators and potential implications. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2017;26:e0100014. doi: 10.1590/0104-07072017000100014

- Berben L, Geerits D, Deliens L, Beeckman D, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, et al. Providing a nurse-led complex nursing intervention focused on quality of life assessment on advanced cancer patients: The INFO-QoL pilot trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021 Aug;53:101982. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101982. PMID: 33984605.

- Drach-Zahavy A, Goldblatt H, Maissel O, Tal-Or D, Admi H. Experiences and perspectives of patients and clinicians in nurse-led consultations in oncology: A multi-methods study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022 Dec;61:102205. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102205. PMID: 36240680.

- Grassi L, Caruso R, Galli F, Nanni MG, Riva S, Sabato S, et al. The effect of consultations performed by specialised nurses or physicians on patient outcomes: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2024 Feb;80(2):215–229. doi:10.1111/jan.15931.PMID: 38945063.

- Bettencourt E., et al. The Role of Case Management in Enhancing Cancer Patient Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2020; 15(4): 345–354. DOI: 10.1016/j.jon.2020.04.005.

- Katerenchuk J, Salas AS. An integrative review on the oncology nurse navigator role in the Canadian context. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2023;33(4):385-99. doi: 10.5737/23688076334385.

- Pautasso FF, Zelmanowicz ADM, Flores CD, Caregnato RCA. Role of the nurse navigator: integrative review. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2018;39:e2017-010. doi: 10.1590/1983-1447.2018.2017-0104

- McMullen L. (2013). Oncology nurse navigators and the continuum of cancer care. Seminars in oncology nursing, 29(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2013.02.005

- Laari, L., & Duma, S. E. (2023). Barriers to nurses health advocacy role. Nursing ethics, 30(6), 844-856. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330221146241

- Laari, L., & Duma, S. E. (2023). Health advocacy role performance of nurses in underserved populations: A grounded theory study. Nursing open, 10(9), 6527–6537. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1907

- Benjamin, L. S., Shanmugam, S. R., Karavasileiadou, S., Hamdi, Y. S. A., Moussa, S. F., & Gouda, A. D. K. (2024). Facilitators and Barriers for Advocacy among Nurses-A Cross-Sectional Study. The Malaysian Journal of Nursing (MJN), 16(1), 178-188. https://doi.org/10.31674/mjn.2024.v16i01.018

- Oliveira, C., & Tariman, J. D. (2017). Barriers to the patient advocacy role: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Practice Applications & Reviews of Research, 7(2), 7-12. https://doi.org/10.13178/jnparr.2017.0702.0704

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

SUBSET OF NANDA-I NURSING DIAGNOSES FOR INTENSIVE CARE: DELPHI TECHNIQUE AND FOCUS GROUP

Mirko Masciullo 1, Flavio Marti 1,2*, Antonello Cocchieri 3, Lucia Mitello1, Andrea Fidanza 1, Anna Rita Marucci 1

- Department of Health Profession, San Camillo Forlanini Hospital, 00152 Rome, Italy

- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, 00189 Rome, Italy

- Section of Hygiene, Woman and Child Health and Public Health, Gemelli IRCCS University Hospital Foundation, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, 00168 Rome, Italy

* Corresponding author: Flavio Marti, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, San Camillo Forlanini Hospital, 00152 Rome, Italy – ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9569-3329 - Email: flavio.marti@uniroma1.it

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The NANDA-I taxonomy classifies nursing diagnoses to standardise communication and illustrate the impact of nursing on health outcomes. To improve usability in clinical practice, subsets of diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes have been developed for specific healthcare settings. These subsets facilitate documentation and decision making while supporting, rather than replacing, the clinical judgment of the nurse.

Objective: The study aims to develop a Subset of NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses that nurses consider relevant in an intensive care setting.

Materials and Methods: A two-round Delphi study was carried out at the A.O. San Camillo Forlanini of Rome to identify the most appropriate diagnoses to constitute the Subset. Using the Delphi technique, two anonymous online questionnaires were submitted to a group of 10 experts. The nurses involved expressed their level of consensus on each of the most used NANDA-I diagnoses in intensive care.

Results: Nurses evaluated a total of 51 NANDA-I nursing diagnoses using 5-level Likert scales, including 47 diagnoses in the Subset. The most representative ones were: "(00004) Risk of infection", "(00047) Risk of compromised skin integrity", "(00030) Compromised gas exchange", "(00091) Compromised mobility in bed", "(00198) Model of disturbed sleep", "(00249) Risk of pressure injury in adults".

Conclusion: Among the included diagnoses, "Risk of infection" received unanimous agreement, confirming its essential role in intensive care. Other highly rated diagnoses, such as "Risk of compromised skin integrity," "Impaired gas exchange," and "Deficit in Self-Care: Bathroom," aligns with findings from previous studies. Some diagnoses, including "Compromised mobility in bed" and "Disturbed sleep pattern," were less commonly used in other ICUs, but were considered highly relevant by Delphi participants. The results highlight the focus of nurses on infection prevention, hygiene, gas exchange, pain management, mobilisation, and prevention of pressure injury. In particular, diagnoses related to stress, family conditions, and emotional needs received a lower consensus, suggesting the need for future research on holistic nursing care.

Keywords: nursing diagnoses, standardised nursing terminology, intensive care units, NANDA-International.

INTRODUCTION

The NANDA-I taxonomy was developed to classify nursing diagnoses related to interventions and outcomes that define the nursing process, allowing the integration of a common language within the nursing profession to improve communication, standardise care and improve patient outcomes. [1]. Standardised nursing terminology arises from the need to accurately and uniformly describe patient care. These terminologies facilitate communication by accurately describing the nursing process and illustrating the impact of nursing on health outcomes [2]. The use of standardised and validated language in clinical practice remains less widespread than expected, in part due to the challenges of integrating a common language into routine nursing documentation [1]. To simplify the use of standardised nursing languages, subsets of diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes have been developed to describe nursing actions in specific healthcare settings [3]. Subsets include specific nursing diagnoses for a specific healthcare context or condition. They are very useful tools for directing appropriate interventions and outcomes based on the clinical judgment of the nurse, who can thus focus on each individual care need of the patient [4]. The concept of Subset was introduced to respond to the need of professionals to have standardised terminology available but at the same time less confusing and easy to use. It is important, however, to specify that a Subset does not replace the nurse's judgment in any way, but rather facilitates the documentation phase of care [5].

Objective: The study aims to develop a Subset of NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses that nurses consider relevant in an intensive care setting. The most commonly used NANDA-I diagnoses in Intensive Care, identified in a recent scoping review [6], were evaluated by a group of Intensive Care nurses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A two-round Delphi study was carried out to identify relevant nursing diagnoses following Skulmoski's methodology [7]. The main purpose of the Delphi technique is to generate consensus among a group of experts through a process of questionnaires interspersed with controlled [8]. It involves a structured group interaction, where members interact anonymously using questionnaires, thus preserving open discussions from influencing results [9]. Multistage interactions are envisaged to reduce the range of responses as much as possible and obtain consensus from the majority of experts [10].

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria required having at least 24 months of experience in an intensive care unit of the A.O. San Camillo Forlanini in Rome.

Sample size

A group of 10 nurses were recruited, with two representatives for each of the five Intensive Care Units (ICU) of the A.O. San Camillo Forlanini of Rome (Shock and Trauma ICU, Cardiovascular ICU, Thoracic ICU, Post-surgical ICU and Neurosurgical ICU). Studies suggest an optimal Delphi group size of 10 and 15 participants [10].

Focus Group

In September 2023, the 10 study participants joined an online focus group via Google Meet. The group received a briefing on the Delphi technique and study procedures. During this session (Round 1), the first anonymous questionnaire was administered through Google Forms. The questionnaire asked to evaluate nursing diagnoses according to the NANDA-I 2020-2023 taxonomy most used in intensive care settings. After completing the questionnaire, an open discussion between participants was held to indicate further NANDA-I nursing diagnoses that should be included in the second questionnaire