Exploring the impact of Nurse Manager Leadership Styles on Nurses' Job Performance at Hamad Medical Corporation: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui 1, 2, *, Mehdi Halleb 1, Maha Mohamed Marzouk Ahmed 1,

Osama Helmi Mohammad Subih 1, Nabil Ajjel 1

- Department of Nursing, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar.

- Institut Universitaire de Formation des Cadres (INUFOCAD), Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

* Corresponding author: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Graduate Registered Nurse, Department of Nursing, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar. PhD Student in Education and Governance, Institut Universitaire de Formation des Cadres (INUFOCAD), Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Email: ghalgaouiabdelbasset@gmail.com

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Nurse performance is vital to patient safety and organizational effectiveness. Leadership style is a recognized determinant of performance, influencing consistency, adaptability, and professional growth. Understanding these dynamics is particularly important in multicultural healthcare environments.

Objective: This study explored the impact of nurse manager leadership styles on nurses’ job performance at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC).

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 980 registered nurses recruited through random sampling. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire including socio-demographic characteristics, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X), and the Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI). Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26, applying descriptive statistics, and Spearman’s correlation, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests.

Results: The workforce was predominantly female (72.1%), married (83.7%), and expatriate, with a mean age of 40.4 years. Transactional leadership (2.57 ±085) was the most common style, followed by transformational (2.20±1.05), while passive-avoidant leadership was minimal (1.49±0.97). Transformational leadership demonstrated strong positive associations with consistency of practice and adaptability. Transactional leadership supported compliance but was less effective in stimulating innovation, while passive-avoidant leadership was negatively correlated with performance outcomes.

Conclusion: Transformational leadership emerged as the most effective style for enhancing nurse performance, while transactional leadership sustained compliance without fostering long-term growth. Strengthening transformational leadership among nurse managers at HMC may improve clinical outcomes, adaptability, and organizational performance.

Keywords: Leadership, Nurses, Job Performance, Practice

INTRODUCTION

In the complex and ever-evolving healthcare environment, the performance of nurses is a cornerstone of quality patient care and organizational success [1–4]. Nurses are at the forefront of healthcare delivery, directly influencing patient outcomes, safety, and satisfaction through their clinical skills, critical thinking, and interpersonal interactions [5–7]. The effectiveness with which nurses execute their duties is not solely dependent on their individual competencies but is significantly shaped by the leadership they receive. Nurse managers, in particular, play a crucial role in fostering an environment that optimizes nursing performance, as their leadership styles directly influence the motivation, development, and productivity of their teams [8].

Job performance in nursing encompasses a broad range of behaviors and outcomes, including adherence to protocols, clinical proficiency, teamwork, communication, and adaptability to challenging situations. High-performing nursing teams contribute to reduced medical errors, improved patient recovery rates, and enhanced overall efficiency within healthcare institutions [9–12]. The leadership styles employed by nurse managers have a profound impact on the performance of their nursing staff. Transformational leadership, characterized by its emphasis on inspiring, empowering, and intellectually stimulating nurses, is often associated with higher levels of performance, as it encourages innovation, professional growth, and a strong sense of ownership [13–16]. This style promotes a positive work environment, which is crucial for fostering high performance. In contrast, transactional leadership, which relies on clear directives, rewards, and corrective actions, can ensure compliance with standards but may not always foster the proactive and adaptive behaviors essential for complex clinical environments [17–19]. Passive-avoidant leadership, marked by a lack of engagement and decision-making, typically has detrimental effects on performance, leading to confusion and disorganization[8]. Recent studies continue to highlight the importance of effective nursing leadership in driving performance outcomes [8,14–19].

While existing literature has explored the relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and job performance, there remains a specific research gap concerning the context of Qatar. Studie in Qatar have investigated aspects such as the generational gap between nurses and nurse managers and its potential impact on job performance [20] . However, a comprehensive understanding of how various nurse manager leadership styles directly influence the diverse aspects of nurses' job performance within the unique healthcare landscape of Qatar, considering its multicultural workforce and specific organizational structures, is still limited. There is a particular need to understand which leadership styles are most effective in promoting optimal job performance among nurses in HMC, given the specific cultural and organizational dynamics of the region.

Objective

This study aims to investigate the specific influence of nurse manager leadership styles on nurses’ job performance at HMC. Specifically, it will examine the relationship between transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles and various dimensions of nursing performance. The insights gained will be invaluable for developing targeted leadership training programs and organizational policies designed to optimize nursing performance, ultimately contributing to superior patient care and the sustained success of HMC's healthcare mission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Type and Classification of Study

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to examine the relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and nurses' job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC).

Comparisons and Predictors of Interest

The primary focus was on comparing various nurse manager leadership styles and their respective impacts on staff nurses’ job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance.

Study Duration

The study was conducted over a period of approximately four months, from November 5, 2024, to March 1, 2025.

Sample Size Justification

To ensure reliability and representativeness of the findings, a sample size calculation was conducted based on a population of approximately 12,000 nurses. Using a 95% confidence level and a ±3% margin of error, a sample size of 980 nurses was determined to be appropriate. The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula:

where Z = 1.96, p = 0.5, e = 0.03.

The value p=0.5 was selected to provide the most conservative estimate and ensure an adequate sample size in the absence of prior data, while margin of error e = ±3% was chosen to achieve high precision and reliable representativeness of the study results.

Study Population and Setting

The study targeted registered nurses employed across different departments at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Qatar. A simple random sampling procedure was used to select participants. The sampling frame consisted of the complete roster of licensed nurses at HMC, with each nurse assigned a unique identification number. Randomization was performed using Microsoft Excel’s RAND function to generate a randomly ordered list.

To mitigate potential non-response, the initial calculated sample of 980 nurses (based on a 95% confidence level and ±3% margin of error for a population of approximately 12,000 nurses) was increased by 245 nurses, resulting in 1,225 nurses being contacted. The questionnaire was distributed to these nurses via their official HMC email accounts, and 980 responses were received and included in the final study sample. This approach ensured equal probability of selection and broad representation across hospitals and nursing units within HMC.

The study was conducted exclusively within HMC facilities.

Inclusion Criteria

- Registered nurses currently employed at HMC.

- Nurses who voluntarily consented to participate.

- Nurses with a minimum of six months of experience at HMC to ensure familiarity with the organizational culture and leadership practices.

Exclusion Criteria

- Nurses on leave or absent during data collection.

- Nurses in managerial or supervisory roles.

- Contract or temporary nurses.

Data Collection

Data were collected via structured online questionnaires distributed through Google Forms. The survey instruments covered the following areas:

- Socio-demographic Data

- Collected information included age, gender, nationality, years of nursing experience, tenure at HMC, education level, hospital, and department.

- Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X)

This 45-item tool assessed leadership styles (transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire) across dimensions such as inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and contingent reward. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = "Not at all" to 4 = "Frequently, if not always") [21].

Items were grouped into their respective leadership dimensions using the MLQ scoring key. For each dimension, a mean score was calculated by summing the responses to the items composing that scale and dividing by the number of valid responses. All leadership style subscales consisted of four items each. Blank or missing responses were excluded from the calculations. Higher mean scores indicated more frequent exhibition of the corresponding leadership behaviors. Leadership dimensions were analyzed as continuous variables rather than categorizing leaders into a single leadership style. The tool demonstrated strong reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.90.

- Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI)

This 20-item instrument assessed nursing performance across clinical and interpersonal dimensions. Responses were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = "Strongly Disagree" to 6 = "Strongly Agree") [22].

NPI scores were calculated by summing the item responses within each domain and dividing by the number of items to obtain mean domain scores. An overall NPI score was computed by averaging all 9 items. Missing responses were excluded from the calculations. Higher scores indicated better perceived nursing performance.

The instrument yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80, indicating strong reliability.

Statistical Considerations and Data Analysis

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

- Primary Outcomes: Nurses’ job performance.

- Secondary Outcome: The relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and the three primary outcomes.

Data Analysis Plan

1. Descriptive Statistics

Summarized participant characteristics and key variables using means and standard deviations (mean±SD), or medians and interquartile intervals (IQR), for numerical data, while ranges, and percentages for qualitative and categorical data.

2. Inferential Statistics

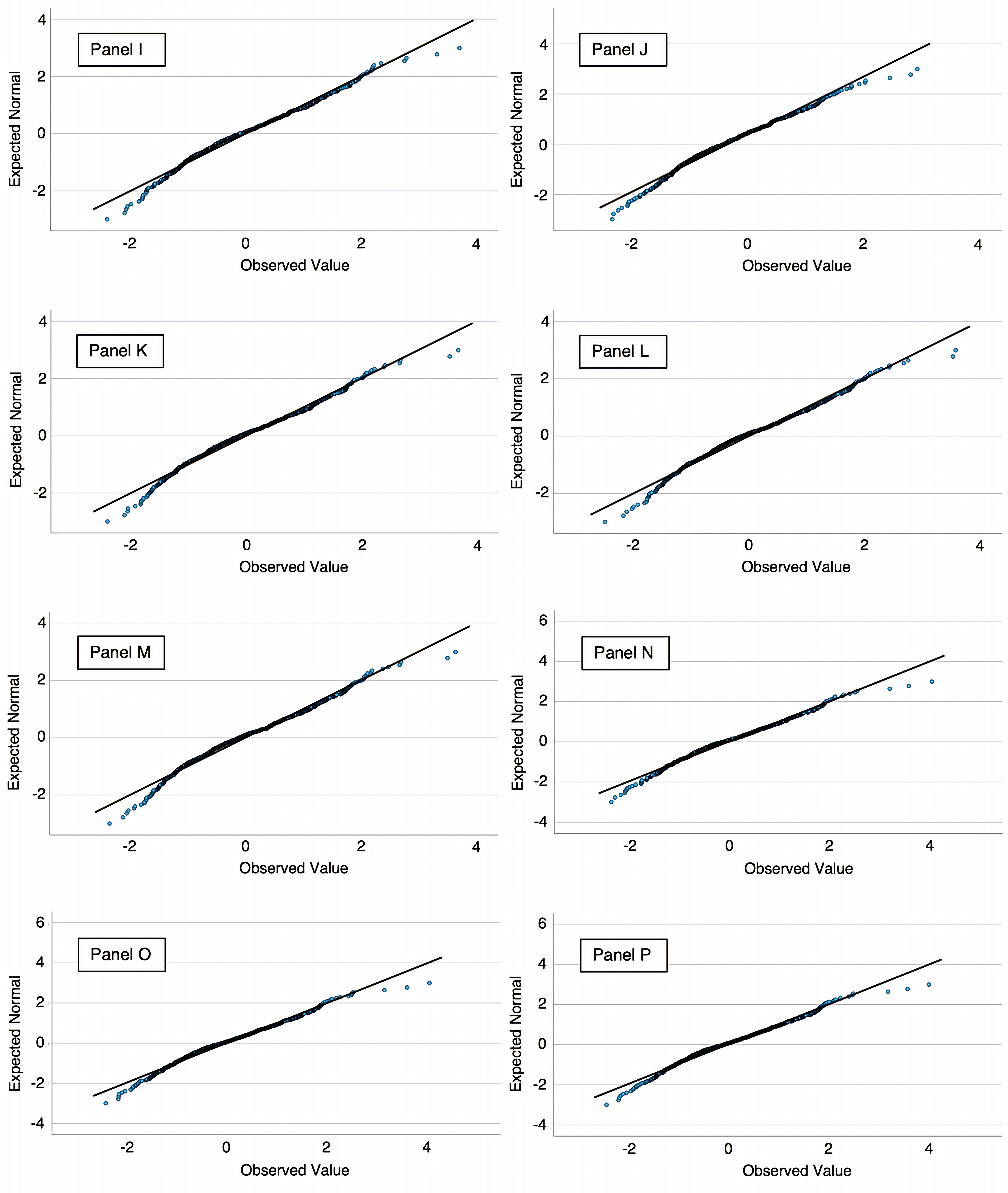

- Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated non-normal distribution (p < 0.05).

- Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient: Used to assess associations between leadership styles and outcome variables.

- Mann–Whitney U Test: Applied to compare differences in outcome variables between two independent groups

- Kruskal–Wallis H Test: Used to compare differences across three or more independent groups

- A p-value (p) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical Software

All analyses were performed using SPSS-26 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences-26).

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature of the study were explained through official internal communication channels via HMC e-mail. Participants provided electronic consent after having at least two months to review the study information before deciding to participate. Only registered nurses employed at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. No financial incentives were offered for participation.

The study was approved by the Medical Research Center (MRC) – Local Ethics Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar (Protocol No. MRC-01-24-356),with approval granted on 15/08/2024, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as well as the regulations of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), Qatar. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the study.

RESULTS

Demographic and Professional Characteristics

The study sample (N=980) exhibits a predominant representation of females (72.14%), while males account for 27.86%. The sex ratio of 0.39 males per female (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | Mean± SD | Median (IQR) |

| Gender | Male | 273 | 27.86 | ||

| Female | 707 | 72.14 | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 138 | 14.08 | ||

| Married | 820 | 83.67 | |||

| Widowed | 8 | 0.82 | |||

| Separated / Divorced | 14 | 1.43 | |||

| Nationality | Cuban | 36 | 3.67 | ||

| Egyptian | 16 | 1.63 | |||

| Filipino | 332 | 33.88 | |||

| Indian | 413 | 42.14 | |||

| Iranian | 3 | 0.31 | |||

| Jordanian | 64 | 6.53 | |||

| Lebanese | 5 | 0.51 | |||

| Palestinian | 8 | 0.82 | |||

| Somali | 3 | 0.31 | |||

| Sudanese | 51 | 5.20 | |||

| Tunisian | 49 | 5.00 | |||

| Age (years) | ≤30 years | 64 | 6.53 |

40.40 ± 7.89 |

37 (35-46) |

| ]30-45] | 657 | 67.04 | |||

| > 45 | 259 | 26.43 |

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics (N=980)

The majority of participants are married (83.67%), with a smaller proportion being single (14.08%) or widowed (0.82%). In terms of nationality, the most represented groups are Indian (42.14%) and Filipino (33.88%), collectively comprising over 75% of the total sample, while other nationalities, such as Jordanian (6.53%), Sudanese (5.20%), and Tunisian (5.0%), are present in smaller proportions. Certain nationalities, including Iranian (0.31%) and Somali (0.31%), have minimal representation. The mean age of the participants is 40.40 ±7.89 years, with a minimum age of 26 years and a maximum age of 62 years. The majority belonging to the 30-45 age group (67.04%), followed by those over 45 years (26.43%), and only a small percentage ≤30 years (6.53%).

The professional characteristics of the study sample (N=980) reveal a workforce with diverse experience levels and educational backgrounds (Table 2). The mean years of experience as a nurse is 16.85 ± 7.14 years, ranging from 3 to 39 years. The majority have 5-15 years of experience (54.29%), followed by those with more than 15 years (43.57%), and a small proportion with ≤5 years (2.14%). Experience within Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) follows a similar trend, with a mean of 9.93 ± 7.54 years, ranging from 1 to 36 years. The distribution shows that 36.73% have ≤5 years, 37.65% have 5-15 years, and 25.61% have over 15 years of experience in HMC.

Regarding education, the majority hold a Bachelor’s degree (76.63%), while 14.18% have a diploma, and 9.18% hold a Master’s degree or higher.

The participants are distributed across various hospitals, with the highest representation from Hamad General Hospital (27.55%), followed by Rumailah Hospital (11.63%), Al Wakra Hospital (11.43%), and Women’s Wellness and Research Center (8.16%). Other facilities, including specialty hospitals like the Communicable Disease Center (1.53%) and The Cuban Hospital (1.73%), have lower representation.

In terms of departmental distribution, the Surgical Department (35.51%) and Medical Department (30.20%) have the highest number of participants, followed by Critical Care/Emergency Services (22.45%) and Outpatient and Ambulatory Services (11.84%).

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | Mean± SD | Median (IQR) |

| Years of experience as a nurse | ≤5 years | 21 | 2.14 |

16.85 ± 7.14 |

15(12-22) |

| ]5-15] | 532 | 54.29 | |||

| > 15 | 427 | 43.57 | |||

| Years of experience in HMC | ≤5 years | 360 | 36.73 |

9.93 ± 7.54 |

7(4-17) |

| ]5-15] | 369 | 37.65 | |||

| > 15 | 251 | 25.61 | |||

| Educational background

|

Diploma | 139 | 14.18 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 751 | 76.63 | |||

| Master’s degree | 90 | 9.18 | |||

| Hospital

|

Hamad General Hospital | 270 | 27.55 | ||

| Ambulatory Care Center | 58 | 5.92 | |||

| Qatar Rehabilitation Institute | 17 | 1.73 | |||

| NCCCR | 19 | 1.94 | |||

| Mental Health Service | 48 | 4.90 | |||

| Communicable Disease Center | 15 | 1.53 | |||

| Al Khor Hospital | 72 | 7.35 | |||

| Rumailah Hospital | 114 | 11.63 | |||

| Al Wakra Hospital | 112 | 11.43 | |||

| Hazm Mebaireek General Hospital | 64 | 6.53 | |||

| Aisha Bint Hamad Al Attiyah Hospital | 63 | 6.43 | |||

| The Cuban Hospital | 17 | 1.73 | |||

| Women's Wellness and Research Center | 80 | 8.16 | |||

| Heart Hospital | 31 | 3.16 | |||

| Department

|

Critical Care / Emergency Services | 220 | 22.45 | ||

| Medical Department | 296 | 30.20 | |||

| Surgical Department | 348 | 35.51 | |||

| Outpatient (OPD) and Ambulatory Services | 116 | 11.84 |

Table 2. Professional Characteristics (N=980)

Nurse Manager Leadership Styles

The results indicate that transactional leadership (2.57±0.85) is more dominant than transformational leadership (2.20±1.05), suggesting that leaders in this sample primarily rely on structured management approaches, such as performance-based rewards (contingent reward, 2.56±1.05) and active monitoring (management by exception – active: 2.58±0.98), rather than fostering innovation, motivation, or individualized consideration (Table 3).

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | S D | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |

| Idealized Attributes or Idealized Influence (Attributes) | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.19 | 1.14 | 2.25 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Idealized Behaviors or Idealized Influence (Behaviors) | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.35 | 1.15 | 2.50 | 1.75 | 3.25 |

| Inspirational Motivation | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.34 | 1.22 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 3.25 |

| Intellectual Stimulation | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.21 | 1.11 | 2.25 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Individual Consideration | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.94 | 0.96 | 2.00 | 1.25 | 2.75 |

| Transformational | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.20 | 1.05 | 2.35 | 1.55 | 3.00 |

| Contingent Reward | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.56 | 1.05 | 2.75 | 2.00 | 3.25 |

| Mgmt by Exception (Active) | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.58 | 0.98 | 2.75 | 2.00 | 3.25 |

| Transactional | 0.25 | 4.00 | 2.57 | 0.85 | 2.62 | 2.00 | 3.12 |

| Mgmt by Exception (Passive) | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.55 | 1.01 | 1.25 | 0.75 | 2.25 |

| Laissez-Faire | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.43 | 1.05 | 1.25 | 0.50 | 2.25 |

| Passive Avoidant | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.49 | 0.97 | 1.37 | 0.75 | 2.12 |

| Extra Effort | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.17 | 1.20 | 2.33 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Effectiveness | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.25 | 1.22 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Satisfaction | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.28 | 1.31 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Outcomes of Leadership | 0.00 | 400 | 2.23 | 1.20 | 2.42 | 1.05 | 3.16 |

Table 3. Nurse Manager Leadership Styles

Within transformational leadership, the highest subscale is idealized influence behaviors (2.35±1.15), indicating that some leaders demonstrate strong role-modeling behaviors. However, individual consideration (1.94±0.96) is the lowest, suggesting that leaders may not provide enough mentorship or personalized support to the nurses.

The passive-avoidant leadership style (1.49±0.97) has the lowest overall scores, particularly laissez-faire leadership (1.43±1.05), indicating that leaders in this sample are generally engaged and do not frequently avoid decision-making. However, the management by exception – passive score (1.55±1.01) suggests that some leaders may still wait until problems arise before taking corrective action.

Regarding leadership outcomes, the scores for effectiveness (2.25±1.22) and satisfaction (2.28±1.31) indicate moderate levels of perceived leader effectiveness and staff satisfaction. Overall outcomes of leadership (2.23±1.20) reflect a tendency towards average performance across the sample, with some variability.

Nurses' Job Performance

The results of the Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI) and its three subscales reveal interesting insights into the nursing workforce’s performance (Table 4).

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | |

| Physical / mental decrement | 1.00 | 6.00 | 2.91 | 1.11 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 3.66 |

| Consistent practice | 1.00 | 6.00 | 4.73 | 1.29 | 5.00 | 4.25 | 5.75 |

| Behavioral change | 1.00 | 6.00 | 3.61 | 1.33 | 3.50 | 3.00 | 4.50 |

| Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI) | 1.00 | 5.78 | 3.88 | 0.94 | 3.88 | 3.44 | 4.44 |

Table 4. Nurses' Job Performance

The subscale "Physical/Mental Decrement" had a mean score of 2.91±1.11, suggesting that nurses report a moderate level of physical and mental strain, though it is not perceived as a severe issue overall. The "Consistent Practice" subscale scored the highest, with a mean of 4.73±1.29, indicating that nurses generally perceive themselves as maintaining consistent and stable practices in their roles. The "Behavioral Change" subscale, with a mean of 3.61±1.33, suggests that there is moderate evidence of behavioral changes in nursing practice. Lastly, the overall NPI score of 3.88±0.94 indicates a generally positive view of nursing performance, reflecting a moderate level overall.

Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses' Job Performance

Female nurses had significantly higher job performance than male nurses (mean rank: 536.67 vs. 370.92, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

| Characteristics | Categories | Mean Rank | Test | p-value (test) |

| Gender

|

Male | 370,92 | 63861,5 | < 0.001 (MW)*

|

| Female

|

536,67 | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 551.12 |

9.513

|

0.009 (KW)*

|

| Married | 472.37 | |||

| Widowed | 457.50 | |||

| Nationality | Cuban | 268.22 | 150.584

|

< 0.001 (KW)*

|

| Egyptian | 389.00 | |||

| Filipino | 576.75 | |||

| Indian | 498.81 | |||

| Iranian | 715.83 | |||

| Jordanian | 298.00 | |||

| Lebanese | 717.70 | |||

| Palestinian | 754.00 | |||

| Somali | 649.17 | |||

| Sudanese | 486.15 | |||

| Tunisian | 198.83 | |||

| Age (years) | ≤30 years | 568.97 | 29.617

|

< 0.001 (KW)*

|

| ]30-45] | 456.10 | |||

| > 45 | 558.38 | |||

| Years of experience as a nurse

|

≤5 years | 509.26 | 1.273

|

0.529 (KW)*

|

| ]5-15] | 481.21 | |||

| > 15 | 501.15 | |||

| Years of experience in HMC

|

≤5 years | 472.97 | 0.003 | 11.533 (KW)* |

| ]5-15] | 472.07 | |||

| > 15 | 542.74 | |||

| Educational background | Diploma | 425.49 | 9.391

|

0.009 (KW)*

|

| Bachelor’s degree | 498.19 | |||

| Master’s degree | 526.72 | |||

| Hospital | Hamad General Hospital | 527.88 | 61.003 | < 0.001(KW)* |

| Al Khor Hospital | 375.75 | |||

| Rumailah Hospital | 428.29 | |||

| Al Wakra Hospital | 458.57 | |||

| Hazm Mebaireek General Hospital | 500.56 | |||

| Aisha Bint Hamad Al Attiyah Hospital | 462.40 | |||

| The Cuban Hospital | 263.56 | |||

| Women's Wellness and Research Center | 481.40 | |||

| Heart Hospital | 607.08 | |||

| Ambulatory Care Center | 531.40 | |||

| Qatar Rehabilitation Institute | 583.32 | |||

| NCCCR | 683.03 | |||

| Mental Health Service | 493.17 | |||

| Communicable Disease Center | 703.83 | |||

| Department | Critical Care / Emergency Services | 492.86 | 43.713 | < 0.001(KW)* |

| Medical Department | 488.47 | |||

| Surgical Department | 440.61 | |||

| Outpatient (OPD) and Ambulatory Services | 640.84 |

Note: MW = Mann–Whitney U test; KW = Kruskal–Wallis H test; *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 5. Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses' Job Performance.

Single nurses reported the highest performance, followed by married and widowed nurses (551.12 vs. 472.37 vs. 457.50, p = 0.009). Significant differences were observed across nationalities, with Palestinian nurses showing the highest performance and Tunisian nurses the lowest (754.00 vs. 198.83, p < 0.001).

Regarding age, nurses aged ≤30 years had the highest performance, followed by those >45 years and those aged 30–45 years (568.97 vs. 558.38 vs. 456.10, p < 0.001). Years of experience as a nurse were not significantly associated with performance, although nurses with ≤5 years of experience had higher performance than those with >15 years or 5–15 years (509.26 vs. 501.15 vs. 481.21, p = 0.529).

Years of experience at HMC were significantly associated with performance, with nurses having >15 years of experience showing the highest performance and those with 5–15 years the lowest (542.74 vs. 472.07, p = 0.003). Educational background influenced performance, with nurses holding a Master’s degree reporting the highest and those with a diploma the lowest (526.72 vs. 425.49, p = 0.009).

Job performance differed significantly across hospitals, with the Mental Health Service reporting the highest and ABAH the lowest performance (703.83 vs. 263.56, p < 0.001). Finally, departmental differences were significant, with the Surgical Department showing the highest performance and the Medical Department the lowest (640.84 vs. 440.61, p < 0.001).

Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Performance

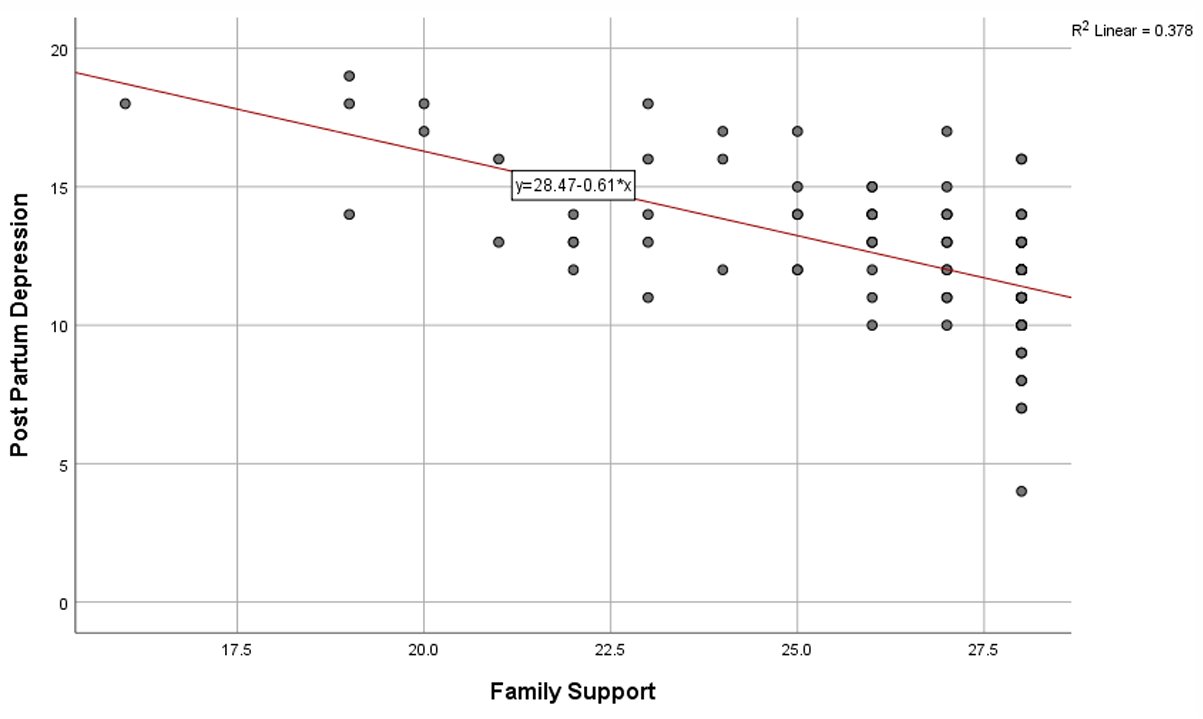

Table 6 explores the relationships between leadership styles and various aspects of nursing performance, including physical/mental decrement, consistent practice, behavioral change, and overall performance measured by the Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI).

Transformational leadership shows a moderate positive correlation with consistent practice (rho = 0.323, p <0.001) and a weak positive correlation with nursing performance (rho = 0.146, p < 0.001). However, there are no significant relationships with physical/mental decrement (rho = 0.017, p = 0.597) or behavioral change (rho = 0.022, p = 0.489). These results suggest that transformational leadership encourages consistent practice and slightly enhances overall performance but does not appear to directly influence nurses' physical or mental well-being or their immediate behavioral adjustments.

|

|

Physical/mental decrement | Consistent practice | Behavioral change | Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI) | |

| Transformational

|

Spearman Coefficient | 0.017 | 0.323 | 0.022 | 0.146 |

| p-value | 0.597 | < 0.001 | 0.489 | <0.001 | |

| Transactional

|

Spearman Coefficient | -0.277 | -0.055 | -0.339 | -0.230 |

| p-value | < 0.001 | 0.083 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Passive Avoidant

|

Spearman Coefficient | 0.038 | -0.073 | -0.087 | -0.121 |

| p-value | 0.233 | 0.022 | 0.006 | < 0.001 | |

Table 6. Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Performance.

Transactional leadership presents a negative correlation with physical/mental decrement (rho = -0.277, p < 0.001), behavioral change (rho = -0.339, p < 0.001), and nursing performance (rho = -0.230, p < 0.001). The correlation with consistent practice is not significant (rho = -0.055, p = 0.083). These findings imply that transactional leadership may be associated with declines in behavioral adaptability and overall performance, potentially reflecting a rigid, reward-punishment dynamic that does not foster flexibility or proactive nursing behaviors.

Passive-avoidant leadership demonstrates weak negative correlations with consistent practice (rho = -0.073, p = 0.022), behavioral change (rho = -0.087, p = 0.006), and nursing performance (rho = -0.121, p < 0.001), though no significant relationship is found with physical/mental decrement (rho = 0.038, p = 0.233). This suggests that passive-avoidant leadership slightly undermines effective nursing practices and performance, likely due to a lack of guidance and support.

In summary, transformational leadership has the most positive influence, especially on consistent practice and overall nursing performance. In contrast, transactional leadership seems linked to negative outcomes, particularly regarding behavioral flexibility and performance, while passive-avoidant leadership also has small but significant negative effects.

DISCUSSION

Demographic and Professional Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the sample provide important context for interpreting job performance outcomes. The high representation of women (72.14%) is consistent with the global nursing workforce [23,24], though the smaller proportion of men (27.86%) may affect team diversity and performance styles [25]. The predominance of married nurses (83.67%) suggests stability, yet also underscores the dual stressors of family and professional responsibilities, which can affect concentration and efficiency [26,27]. The reliance on expatriate staff, especially Indian (42.14%) and Filipino (33.88%) nurses, reflects regional workforce trends but introduces cultural adaptation challenges that may shape performance consistency [28]. The average age (40.40 years) and extensive experience (16.85±7.14 years) demonstrate a mature workforce capable of sustaining performance. However, the limited presence of younger nurses (≤5 years’ experience, 2.14%) may hinder succession planning and innovation. The predominance of bachelor’s degrees (76.63%) indicates solid educational preparation, though the limited advanced degrees (9.18%) highlight opportunities to strengthen specialized competencies.

Nurse Manager Leadership Styles

Leadership findings confirmed transactional leadership (2.57±085) as the dominant style, with contingent rewards (2.56±1.05) and active monitoring (2.58±0.98) driving structured compliance. While these strategies ensure adherence to standards, they may not stimulate the innovation and adaptability increasingly demanded in modern healthcare settings [15,18]. The low emphasis on individual consideration (1.94±0.96) suggests a lack of personalized development, limiting opportunities for performance growth [8]. By contrast, transformational leadership has been consistently linked to enhanced job performance across diverse contexts [14,16]. Although passive-avoidant leadership (1.49±0.97) was rare, its occasional presence risks undermining performance through delayed intervention. These results suggest that adopting transformational leadership at HMC could strengthen consistency, adaptability, and clinical performance.

Nurses' Job Performance

The high consistent practice scores (4.73±1.29) highlight nurses’ reliability in adhering to established protocols, a strength in error-prone healthcare settings. However, moderate behavioral change (3.61±1.33) signals resistance to adapting workflows, possibly due to rigid transactional leadership or fear of reprisal for deviations. The overall performance score (NPI = 3.88) suggests competence but not excellence, aligning with environments prioritizing compliance over innovation. Notably, physical/mental decrement (2.91±1.11) indicates that strain, while not severe, may hinder proactive initiatives. In a similar context in Iran, nurse performance was also reported at a moderate level, with the general performance aspect receiving the highest average score and the mental aspect the lowest [29].

Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses' Job Performance

Job performance varied markedly across demographics. Females outperformed males (p < 0.001), aligning with a study conducted in the same context in Jordan, a Middle Eastern country, which linked female nurses to higher job performance [30]. This gender gap may reflect both enduring social norms around caring roles and targeted soft-skills training that disproportionately benefits female practitioners.

Single nurses showed higher performance (mean rank = 551.12) than married or widowed peers, possibly due to fewer familial responsibilities or greater focus on career progression. This contrasts with studies conducted in Jordan and Turkey, which found no significant relationship between marital status and job performance [30,31]. Nationality-based differences were stark: Palestinian nurses (mean rank = 754.00) excelled, while Tunisians (mean rank = 198.83) underperformed. This may reflect disparities in training quality, language proficiency, or workplace integration. Younger nurses (≤30 years) outperformed older colleagues (p < 0.001), suggesting adaptability to new protocols or technologies. Paradoxically, nurses with >15 years of HMC experience also performed well, indicating that institutional knowledge complements innovation. In the same context, a study conducted in Jordan found that age and experience were related to job performance [30].

Master’s-trained nurses (mean rank = 526.72) outperformed diploma holders, underscoring the value of advanced education in clinical decision-making. Hospitals like the Mental Health Service (mean rank = 703.83). Surgical departments (mean rank = 640.84) reported superior performance, likely due to specialized workflows or interdisciplinary collaboration. These findings advocate for competency-based training and equitable recognition of diverse backgrounds.

Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Performance

Transformational leadership moderately enhanced consistent practice (rho = 0.323, p < 0.001) but had no impact on behavioral change, suggesting it fosters reliability over innovation. The findings partially align with those reported by Mohammed Qtait on 2023, who conducted a systematic review of 12 quantitative studies investigating the relationship between leadership styles and nurse performance, reports that transformational leadership had the strongest positive correlation enhancing nursing care quality, job satisfaction, motivation, and patient outcomes [8].

Transactional leadership correlated negatively with performance (rho = -0.230, p < 0.001), particularly behavioral change (rho = -0.339, p < 0.001), implying rigid reward-punishment systems hinder adaptability. However, Qtait’s review found a moderate positive correlation between transactional leadership and nurse performance, indicating some benefits under structured systems [8].

Passive-avoidant leadership also undermined performance (rho = -0.121, p < 0.001), in line with Qtait’s conclusion that laissez-faire leadership had weak or no positive impact [8]. This consistent finding emphasizes that ambiguity, lack of guidance, and disengagement by leaders can significantly reduce nurse motivation and clarity in roles.

Recommendations

The findings of this study highlight the critical need to strengthen transformational leadership competencies among nurse managers at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC). It is recommended that HMC invest in ongoing leadership development programs that emphasize communication, motivation, and professional empowerment to promote inspiring and participative managerial behaviors. Transformational leadership, by encouraging autonomy and creativity, can significantly enhance both individual and collective nursing performance, fostering consistency in clinical practice and adaptability in complex healthcare settings.

Furthermore, leadership competency assessments should be integrated into managerial performance evaluations to ensure that adopted leadership styles align with organizational goals and contribute to nurse productivity and job satisfaction. Organizational culture should also move toward reducing overreliance on transactional leadership, which focuses primarily on control and rewards, and instead foster more collaborative, innovative, and supportive leadership approaches.

Finally, creating a psychologically and physically supportive work environment is essential to reduce stress and fatigue among nurses, both of which can negatively affect long-term job performance

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study possesses several methodological strengths that enhance its scientific credibility. First, the use of a large and randomly selected sample (N = 980) provides strong representativeness and statistical reliability. The application of validated international instruments, namely the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X) for assessing leadership styles and the Nursing Performance Instrument (NPI) for measuring clinical performance, adds to the study’s methodological rigor. Moreover, the use of robust statistical analyses including Spearman’s correlation, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests enabled comprehensive exploration of relationships between leadership styles and various aspects of job performance, providing a multidimensional understanding of these dynamics. Despite its strengths, the study also presents certain limitations. The most significant is its cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer causality between leadership style and nurse performance. It remains unclear whether transformational leadership directly improves performance, or whether nurses who perform better perceive their leaders as more transformational. Additionally, self-reported data may have introduced response bias, as participants could overestimate their performance due to social desirability or professional pride. Studies would provide a broader and more causal understanding of these leadership–performance relationships.

CONCLUSION

This study clearly demonstrates that nurse manager leadership styles have a significant and differentiated impact on nurses’ job performance within Hamad Medical Corporation. The results reveal that transformational leadership exerts the most substantial positive effect, enhancing consistency in clinical practice, adaptability to change, and overall professional performance. Nurses who perceive their leaders as visionary, supportive, and encouraging are more motivated, committed, and productive. These findings align with international literature showing that transformational leaders foster collaboration, reduce clinical errors, and improve both patient outcomes and staff well-being. In contrast, transactional leadership, while effective in maintaining compliance and operational discipline, tends to have limited influence on creativity and long-term professional growth. Its focus on control and reward systems may sustain performance in routine tasks but fails to nurture the initiative and innovation required in dynamic healthcare environments. On the other hand, passive-avoidant leadership emerges as the least effective style, being associated with disorganization, lack of motivation, and decreased performance due to minimal managerial involvement or guidance.

The implications for nursing leadership are profound. Developing a structured and culturally adaptive transformational leadership model should be a strategic priority for HMC. Such an approach can strengthen clinical performance, enhance innovation, reduce turnover, and promote a collaborative culture focused on quality and patient safety. Ultimately, this study underscores that effective leadership in nursing transcends task management it is fundamentally about mobilizing human potential to achieve excellence, empowerment, and resilience within healthcare organizations.

Local Ethics Committee approval

The study was approved by the Medical Research Center (MRC) – Local Ethics Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar (Protocol No. MRC-01-24-356) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as well as the regulations of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), Qatar. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the study.

Conflicts of interest

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards. All participants provided informed consent. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

This research received funding from the Medical Research Center at HMC.The authors thank the

Author contributions

Conception and design: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui

Data collection: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui

Data analysis and interpretation: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Osama Helmi Mohammad Subih, Maha Mohamed Marzouk Ahmed, Mehdi Halleb, Nabil Ajjel.

Drafting of the manuscript: all authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Mehdi Halleb

Final approval: all authors

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of Hamad Medical Corporation for their collaboration.

REFERENCES

- DeLucia PR, Ott TE, Palmieri PA. Performance in Nursing. Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics. SAGE Publications; 2009;5:1–40. https://doi.org/10.1518/155723409X448008

- El-Gazar HE, Zoromba MA. Nursing Human Resource Practices and Hospitals’ Performance Excellence: The Mediating Role of Nurses’ Performance. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:e2021022. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92iS2.11247

- Gurses AP, Carayon P, Wall M. Impact of Performance Obstacles on Intensive Care Nurses’ Workload, Perceived Quality and Safety of Care, and Quality of Working Life. Health Services Research. 2009;44:422–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00934.x

- Shahnavazi A, Bouraghi H, Eshkiki MF, Shahnavazi H. The Effect of Perceived Organizational Climate on the Performance of Nurses in Private Hospitals [Internet]. Journal of Clinical Research in Paramedical Sciences. Brieflands; 2021 Dec. https://doi.org/10.5812/jcrps.108532

- Bae JY, Bae SH. The Effect of Clinical Nurses’ Critical Thinking Disposition and Communication Ability on Patient Safety Competency. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. Korean Academy of Fundamentals of Nursing; 2022;29:159–69. https://doi.org/10.7739/jkafn.2022.29.2.159

- Saputri CA. The Role of Nursing Interventions in Patient Satisfaction and Outcomes. AHR. 2023;1:75–87. https://doi.org/10.60079/ahr.v1i2.359

- Wieke Noviyanti L, Ahsan A, Sudartya TS. Exploring the Relationship between Nurses’ Communication Satisfaction and Patient Safety Culture. Journal of Public Health Research. SAGE Publications; 2021;10:jphr.2021.2225. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2225

- Qtait M. Systematic Review of Head Nurse Leadership Style and Nurse Performance. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2023;18:100564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2023.100564

- Alrabadi N, Shawagfeh S, Haddad R, Mukattash T, Abuhammad S, Al-rabadi D, et al. Medication errors: a focus on nursing practice. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2021;12:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/jphsr/rmaa025

- Asante BL, Zúñiga F, Favez L. Quality of care is what we make of it: a qualitative study of managers’ perspectives on quality of care in high-performing nursing homes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1090. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07113-9

- Christopher-Dwyer K, Scanlon KG, Crimlisk JT. Critical Care Resource Nurse Team: A Patient Safety and Quality Outcomes Model. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2022;41:46. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000501

- Howell EA, Sofaer S, Balbierz A, Kheyfets A, Glazer KB, Zeitlin J. Distinguishing High-Performing From Low-Performing Hospitals for Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Focus on Quality and Equity. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:1061–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004806

- Bass BM, Riggio RE. Transformational Leadership. Psychology Press; 2006.

- Hasan AA, Ahmad SZ, Osman A. Transformational leadership and work engagement as mediators on nurses’ job performance in healthcare clinics: work environment as a moderator. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). 2023;36:537–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-10-2022-0097

- Wang H-F, Chen Y-C, Yang F-H, Juan C-W. Relationship between transformational leadership and nurses’ job performance: The mediating effect of psychological safety. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal. 2021;49:1–12. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.9712

- Wijayanti K, Aini Q. The Influence of Transformational Leadership Style to Nurse Job Satisfaction and Performance in Hospital. Journal of World Science. 2022;1:485–99. https://doi.org/10.58344/jws.v1i7.69

- Al-Rjoub S, Alsharawneh A, Alhawajreh MJ, Othman EH. Exploring the Impact of Transformational and Transactional Style of Leadership on Nursing Care Performance and Patient Outcomes. Journal of Healthcare Leadership. Dove Medical Press; 2024;16:557–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S496266

- Mekonnen M, Bayissa Z. The Effect of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles on Organizational Readiness for Change Among Health Professionals. SAGE Open Nursing. SAGE Publications Inc; 2023;9:23779608231185923. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608231185923

- Suwarno B. Analysis Head Nurses’ Leadership Styles to Staff Inpatient Nurses’ Job Performance in Hospital. International Journal of Science, Technology & Management. 2023;4:317–26. https://doi.org/10.46729/ijstm.v4i2.770

- Abujaber AA, Nashwan AJ, Santos MD, Al-Lobaney NF, Mathew RG, Alikutty JP, et al. Bridging the generational gap between nurses and nurse managers: a qualitative study from Qatar. BMC Nurs. 2024;23:623. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02296-y

- Avolio BJ, Bass BM. Multifactor leadership questionnaire: manual and sample set. Third edition. Place of publication not identified: Mind Garden, Inc.; 2004.

- Sagherian K, Steege LM, Geiger-Brown J, Harrington D. The Nursing Performance Instrument: Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses in Registered Nurses. J Nurs Res. 2018;26:130–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000215

- Kharazmi E, Bordbar N, Bordbar S. Distribution of nursing workforce in the world using Gini coefficient. BMC Nursing. 2023;22:151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01313-w

- State of the world’s nursing report 2025 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sept 22]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240110236. Accessed 22 Sept 2025

- Shen J, Guo Y, Chen X, Tong L, Lei G, Zhang X. Male nurses’ work performance: A cross sectional study. 2022;101:e29977. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029977

- Al-Hasnawi AA, Aljebory MKA. Relationship between nurses’ performance and their demographic characteristics. Journal Port Science Research. 2023;6:11–5. https://doi.org/10.36371/port.2023.1.3

- Hwang E, Yu Y. Effect of Sleep Quality and Depression on Married Female Nurses’ Work–Family Conflict. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021;18:7838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157838

- Turjuman F, Alilyyani B. Emotional Intelligence among Nurses and Its Relationship with Their Performance and Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study. Alamri M, editor. Journal of Nursing Management. 2023;2023:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5543299

- Niri M al-SM, Khademian Z, Rivaz M. Nurses’ Performance as a Mediator Between Nurses’ Fatigue and Patient Safety Culture: A Structural Equation Model Analysis. Nursing Open. 2025;12:e70168. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.70168

- Al-Harazneh R, Abu shosha GM, Al-Oweidat IA, Nashwan AJ. The influence of job security on job performance among Jordanian nurses. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2024;20:100681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2024.100681

- Ari HO. Determining the Relationship Between Work Stress and Job Performance: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Healthcare Workers. Journal of Nursing Management. 2025;2025:5051149. https://doi.org/10.1155/jonm/5051149

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

SELF-CARE KNOWLEDGE, BEHAVIORAL PRACTICES, AND PREVENTIVE STRATEGIES FOR DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS AMONG INDIVIDUALS WITH DIABETES IN TERTIARY HOSPITALS IN NIGERIA: A CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY

Oseni Rukayat Ejide ¹, Emmanson Emmanson ²*, Kolawole Ifeoluwapo ¹,

Adejumo Prisca1, Obilor Helen3

- Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

- Department of Human Anatomy, University of Cross River State, Nigeria

- School of Nursing, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Emmanson Emmanson, Department of Human Anatomy, University of Cross River State, Nigeria. Email: emmansonemmanson35@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7285-7574

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The increasing prevalence of diabetes is a global public health concern, with foot ulcer prevention techniques, low self-care knowledge, and a lack of confidence contributing to complications like foot ulcers.

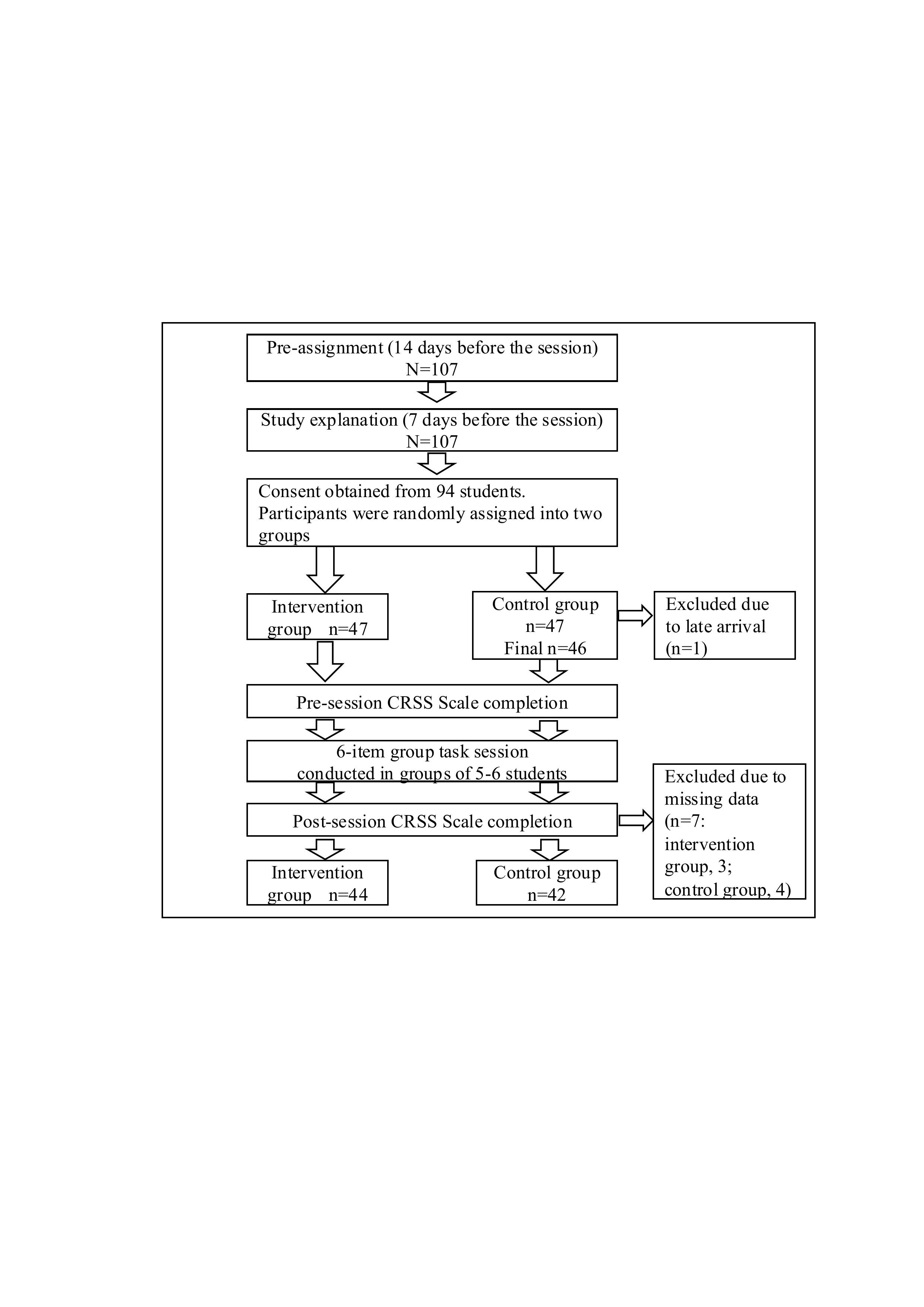

Methods: This cross-sectional study, conducted between January and December 2022, evaluated foot self-care knowledge, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviors among individuals with diabetes attending public tertiary hospitals in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Data from randomly selected 120 out-patients was collected using a multidimensional questionnaire, and multiple regression analysis was used to assess associations between variables.

Results: It was found that participants’ mean age was 44.8±14.65 years. Majority (58.3%) of them did not attend foot self-care education classes and had received a type-2 diabetes diagnosis within the previous 24 months. Many of the patients had low knowledge of foot self-care (55%), low self-care efficacy (55%) and poor self-care behavior (55%). Poor self-care behavior was predicted by low efficaciousness (p<0.0001) and low knowledge of foot self-care (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: The study concluded that the extent of knowledge significantly influenced self-care behaviors and the efficacy of foot self-care in averting diabetic foot ulcers. Improving these behaviors requires teaching appropriate knowledge through hands-on self-care treatments and gaining support from policymakers for its sustainability.

Keywords: Diabetes Foot Ulcer, Self-Care Knowledge, Efficacy, Behavior, Confidence.

INTRODUCTION

With an increasing prevalence, diabetes mellitus has become a global public health concern [1]. It raises mortality, illness, and medical expenses [1,2]. There are 537 million adults (20–79 years old) worldwide with diabetes as reported by International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [1]. Conversely, by 2060, the incidence of diabetes is expected to increase to 700% for type II and 65% for type I, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [3]. Additionally, diabetes is thought to be the cause of 6.7 million fatalities annually [1], with 1.5 million of those deaths occurring primarily in low- and middle-income nations [4].

According to IDF data from 2021, 1 in 22 adult Africans has diabetes, and 54% of Africans have diabetes but have not been diagnosed [1]. In Nigeria, the prevalence of diabetes rose from 2.2% in 1997 to over 6% in 2015, a more than 100% increase, according to World Health Organization (WHO) [5]. The IDF stated that the sub-Saharan region had the greatest estimated prevalence of diabetes, at 3,623,500 (3.7%). The prevalence rates of diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) in Nigeria vary from 11% to 32%, according to Ugwu et al. [6]. The rising rate of diabetes in Nigeria has been mostly linked to demographic shifts, including urbanization, the adoption of unsafe habits, poor diets that include sugar-sweetened beverages, inactivity, and dangerous alcohol and tobacco use [5,6]. This has also led to complications such as diabetic foot ulcers. This necessitates investigating the level of knowledge of people with diabetes mellitus (PWDM) on foot ulcer preventive self-care activities in selected hospitals in Abeokuta.

Millions of individuals worldwide are impacted by the dangerous side effect of diabetes called diabetic foot ulcers. It is lethal and can cause gangrene, infection, ischemia problems, neuropathy, macrovascular disease, and microvascular damage. According to Robles et al. [7], DFU is a challenging, expensive, and chronic health problem that increases morbidity and death. According to Oliver and Mutlouglu [8], ulcers are typically persistent and can occur in inpatient as well as outpatient environments. An array of variables, such as male gender, diabetes for over a decade, the advanced age of the patients, obesity, dry skin, insufficient circulation, underpinning nerve damage, callus formation, foot defects, improper foot hygiene, and poorly fitting shoes, are linked to the development of DFU, according to Khan, Khan, & Farooqui [9] and Oliver & Mutlouglu, [8]. Despite being controllable through education, it is the most costly and fatal event related with lower extremity amputation (LEA) and frequently associated with high morbidity and death [6]. Families and societies are consequently forced to bear a greater financial burden [10,11]. Other adverse effects include poor quality-of-life [12, 13]. In light of these burdens, it is important to assess how confident PWDM are in their ability to avoid foot ulcers in the selected hospitals. Therefore, this study assumes there is no significant association between efficacy and behavior of PWDM.

According to Sari et al. [14], poor foot self-care is the main factor contributing to DFU, while appropriate foot self-care can cut the risk of DFU, hospital stays, and amputations by 50%. Client-focused education on self-efficacy in FSC practices should be promoted in a time- and cost-effective manner, as continuous physician supervision is not always possible [15]. For this reason, Adeyemi et al. [16] proposed that appropriate foot care methods and patient education can avoid or lower the risk for DFU in the interim. Previous studies [9,14,17,18] revealed low to moderate foot care practice, inadequate understanding of DFU, and attitudes toward foot care prevention. People with diabetes mellitus in Sub-Saharan Africa also showed fair but insufficient awareness of diabetic foot care [19]; this is comparable to what is available in other parts of the world. Research on effective FSC behavior is still limited, and incidence of DFU, limb loss, and DFU-related premature death have increased in Nigeria. Similar to what was found by Ojewale, Okoye, and Ani [20], their study on FSC behavior and self-efficacy among PWDM in the University College Hospital, Nigeria, revealed a scarcity of investigations. Consequently, research on PWDM self-care knowledge, efficacy, and behavior is crucial. It is therefore important to explore the foot self-care behavior of PWDM in selected hospitals. In line with this, the study tested the hypothesis that there is no significant association between age, gender, educational status and behavior of FSC among PWDM, and that there is no significant association between knowledge of FSC and the behavior of PWDM. Thus, with the goal to prevent foot ulcers, this study assessed PWDM's self-care knowledge, efficacy, and behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study which assessed the FSC knowledge, self-care efficacy and behavior of PWDM toward DFU prevention in Federal Medical Hospital (FMC), and State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta, Nigeria, between January and December 2022.

Target population

This included PWDM (type 1 and 2) in the selected hospitals.

Study population

PWDM who attended outpatient clinics, who were estimated to be 200 monthly in FMC, and 120 monthly in the State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta, respectively.

Inclusion criteria

Adult PWDM male and female aged 18 years and above managed for at least three months, that attended OPD clinic of FMC and State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta and gave consent to participate were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

PWDM with existing DFU, those critically ill, and those on admission were excluded from the study.

Sample size estimation

The minimum sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for estimating proportions in large populations:

where:

n0 = initial sample size, Z = standard normal deviation at 95% confidence (1.96), p = estimated proportion of the population with the attribute, q = 1 – p, e = desired margin of error.

Since no prior prevalence estimate of foot-care knowledge among individuals with diabetes in Abeokuta was available, the study used p = 50%. This value is conventionally used when there is insufficient prior data, as it maximizes sample size and increases precision. The margin of error was set at e = 10%. Based on previous values the estimated sample size is:

Additionally, a 20% attrition rate (AR) was included:

![]()

Thus, the final sample size used in this study was 120. Particularly, we adopted a relatively large margin of error (e=10%) and an attrition rate of 20%, as this is an explorative study.

Sampling technique

Two out of the three hospitals in Abeokuta; Federal Medical Center, Abeokuta and State Hospital, Ijaiye were selected using random sampling technique. A total of 120 participants were later recruited from the 2 hospitals.

Instrument for data collection

Data was obtained from respondents using structured and validated questionnaires, the questionnaire was in three sections. Section A addressed demographic data and knowledge of FSC. Section B assessed FSC behavior activities using a validated 26-item self-report tool adapted form of Nottingham Assessment of Functional Foot-care (NAFFS) [21]. While section C addressed the question on foot care efficacy using an adapted 12-item Foot Care Confidence Scale (FCCS) by Sloan Helen L. (2002) [22].

Validity of the instrument

The instrument was subjected to face and construct validity by thorough scrutiny by the researcher’s supervisor and expert clinician caring for PWDM and DFU. The multidimensional validated questionnaire containing sections on FCCS and NAFFS was subjected to forward and backward translation to Yoruba and English to ensure their validity. The items in each section of the instrument were further subjected to content validity testing by submitting the instrument to five experts and using Lawshe's formula to ensure the content validity ratio (CVR) for each item in each section of the instrument, resulting in the content validity index (CVI) for each section. According to Ayre and Sally (2013) [23], the CVR (content validity ratio) proposed by Lawshe (1975) [24] is a linear transformation of a proportional level of agreement on how many “experts” within a panel rate an item “essential” calculated in the following way:

CVR is the content validity ratio, ne is the number of panel members indicating an item “essential,” and N is the number of panel members.Just like r, CVR ranges between -1 through 0 to +1.

The closer to +1 is CVR for an item; the more valid is the item in the scale while CVR values closer to 0 imply lack of content validity. However, CVI is computed by dividing sum of CVR values by the total number of items. CVI is interpreted for the scale the same way CVR values are interpreted for the items. Table 1 displayed the CVIs for the relevant sections of the multidimensional instrument:

|

Instrument |

Number of Items |

Content Validity Index (CVI) |

Comment |

|

Foot Self-care Knowledge scale |

7 |

0.84 |

Valid |

|

FCCS |

12 |

0.76 |

Valid |

|

NAFFS |

26 |

0.86 |

Valid |

Table 1. Validity table

Reliability of the instrument

The reliability of the knowledge part of the questionnaire in section A was established using the Kuder Richardson formula- 20, KR20 conducted on SPSS Version 23 because of the dichotomous nature of the items in the section of the multidimensional instrument. Though the other 2 validated instruments, FCCS and NAFFS reportedly had Cronbach’s alpha reliability indices of 0.92 and 0.91 respectively, but all these instruments were revalidated by administering them on a sample of 30 respondents similar to but entirely different from those recruited for the main study. The reliability index obtained for the instruments was > 0.9 (Table 2).

|

Instrument |

Number of items |

Cronbach Alpha/KR20 |

Comment |

|

Foot Self-care Knowledge scale |

7 |

0.972 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

|

FCCS |

12 |

0.996 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

|

NAFFS |

26 |

0.997 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

Table 2. Reliability indices for the variables in the multidimensional instrument

Method of data collection

After gaining approval from the two institutions' ethical committee, the individual's informed consent, and permission from the head of the OPD at both, the instruments for data collection were given to study participants on clinic days over the course of four months (July to October, 2023), two research assistants attended a two-day training session where they learned about the objectives of the study, the content of foot care and DFU prevention guidelines/standards, FSC behavior and self-efficacy tools, and how to distribute the questionnaires. They were selected from among the registered nurses who care for patients with diabetes and DFU at Sacred Heart Hospital, Lantoro. Targeting their clinic hours on Mondays and Wednesdays, the study settings (FMC and State Hospital, Ijaye, respectively) were visited in the morning. As soon as the surveys were completed, they were gathered. People who were illiterate were helped to complete the surveys by having them translated into their native tongue.

Method of data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables.

Responses to attitudinal or perception-based questions were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree). Where applicable, composite scores were computed, and the scale reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Inferential statistics, including chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t-tests or ANOVA for comparing group means, were applied where appropriate.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data were entered and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty questionnaires were administered to the respondents, same received and used for analysis.

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

Mean |

SD |

|

Age (years) |

21–30 |

28 (23.3) |

||

|

31–40 |

24 (20.0) |

|||

|

41–50 |

21 (17.5) |

|||

|

51–60 |

26 (21.7) |

44.8 |

14.65 |

|

|

61–70 |

17 (14.2) |

|||

|

>70 |

4 (3.3) |

|||

|

Gender ᵃ |

Female |

85 (70.8) |

1.29 |

0.46 |

|

Male |

35 (29.2) |

|||

|

Marital status ᵇ |

Single |

30 (25.0) |

2.13 |

0.90 |

|

Married |

55 (45.8) |

|||

|

Separated/Divorced |

24 (20.0) |

|||

|

Widowed |

11 (9.2) |

|||

|

Educational status ᶜ |

No formal education |

28 (23.3) |

2.55 |

1.13 |

|

Primary |

31 (25.8) |

|||

|

Secondary |

28 (23.3) |

|||

|

Tertiary |

33 (27.5) |

|||

|

Occupation ᵈ |

Unemployed |

28 (23.3) |

2.53 |

1.08 |

|

Farming |

28 (23.3) |

|||

|

Trading |

37 (30.8) |

|||

|

Civil servant |

27 (22.5) |

|||

|

Type of diabetes ᵉ |

Type 1 |

50 (41.7) |

1.58 |

0.50 |

|

Type 2 |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Duration since diagnosis ᶠ |

1–24 months |

87 (72.5) |

1.47 |

0.87 |

|

25–48 months |

17 (14.2) |

|||

|

49–72 months |

9 (7.5) |

|||

|

>72 months |

7 (5.8) |

|||

|

Previous foot–care education ᵍ |

Yes |

50 (41.7) |

1.58 |

0.50 |

|

No |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Foot-care frequency ʰ |

Once a week |

16 (13.3) |

2.75 |

1.59 |

|

2–6 times/week |

22 (18.3) |

|||

|

Once a day |

8 (6.7) |

|||

|

>1 time/day |

4 (3.3) |

|||

|

Not applicable |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Knowledge of foot care ⁱ |

No idea |

72 (60.0) |

0.48 |

0.65 |

|

Moderate idea |

38 (31.7) |

|||

|

Expert idea |

10 (8.3) |

|||

|

Performs foot care independently ʲ |

Yes |

87 (72.5) |

1.28 |

0.45 |

|

No |

33 (27.5) |

|||

|

**If No, who helps? **ᵏ |

Family |

31 (25.8) |

2.02 |

0.98 |

|

Friends |

2 (1.7) |

|||

|

Not applicable |

87 (72.5) |

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of 120 respondents (Source: Field survey, 2023)

Table 3 showed the demographic distribution of the respondents. The majority 28 (23.1%) of them are in the age group of 21-30 years, while the 4 (3.3%) that were above 70 years were the least in the distribution with the mean age of 44.8±14.65 years. About three-quarters 85 (70.8%) are female, while 35 (29.2%) are male. The majority were married, 55 (45.8%), and 30 (25%) are single. Most of the respondents had higher education 33 (27.5%), while both illiterates and secondary school completers were 28 (23.3%), respectively. Traders were more than other categories at 37 (30.8%) followed by civil servants at 27 (22.5%).

As shown further in Table 3, more than half 70 (58.3%) of the respondents had T2DM with majority 87 (72.5%) diagnosed within the past 24 months. Findings also revealed that 50 (41.7%) of the respondents had prior attendance at FSC education while 70 (58.3%) had no such experience. A few, 16 (13.3%), 22 (18.3%), 8 (6.7%) and 4 (3.3%) of the participants attended once a month, every other month, whenever chanced, and when reminded respectively, while this was not applicable to 70 (58.3%) of them. The majority, 72 (60.0%) of the participants had no idea know what foot care is, 38 (31.7%) had moderate idea while 10 (8.3%) claimed to have expertise idea. Finally, 87 (72.5%) performed foot care by themselves while 33 (27.5%) did not.

Respondents’ knowledge of foot self-care

|

Item |

No |

Yes |

|

|

People with diabetes should check their feet at least once a day |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should inspect their toes, nails, and cut it straight |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

The feet should be washed, and lotion applied to moisturize them |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should warm their feet with lantern |

66(55%) |

54(45%) |

|

|

Before putting on shoes, people with diabetes should inspect the interior of them |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

|

|

Foot corn/callus should be removed with razor blade |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should wear shoes that are not too tight |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

Table 4. Knowledge of 120 respondents on foot self-care (Source: Field survey, 2023)

From table 4 the majority 77 (64.2%) of the participants declined that, PWDM should check their foot once daily, inspect their toes, nails, and cut it straight and the feet should be washed, and lotion applied to moisturize them. A little above half 66 (55.0%) disagreed with the statement that PWDM should warm their feet with lantern. Additionally, 44 (36.7%) of the respondents indicated that PWDM should wear shoes that are not too tight, remove corns and calluses from their feet with a razor blade, and check the inside of their shoes before wearing them.

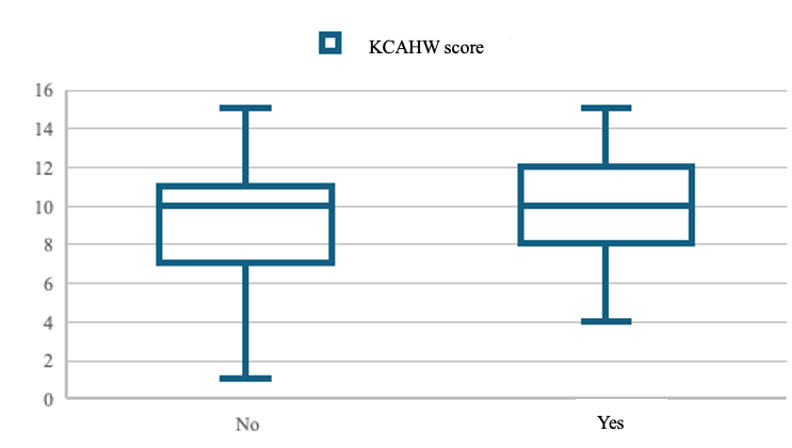

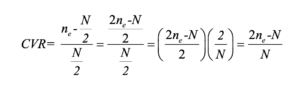

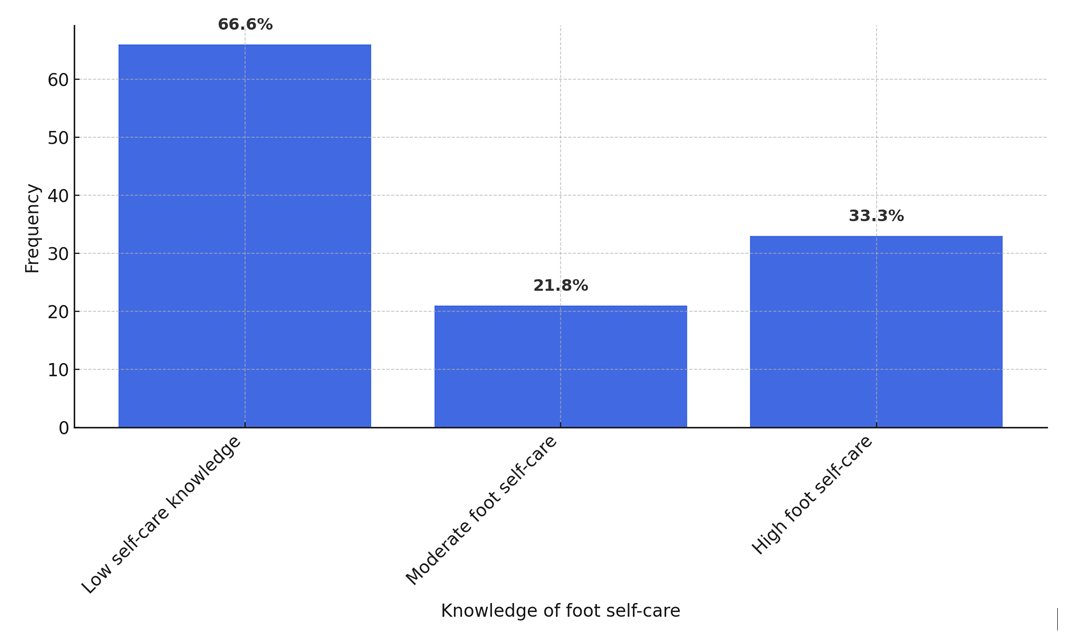

Summary of respondents’ knowledge about foot self-care

Overall, the mean knowledge score was 9.63+3.08. As shown in Figure 1, 55% of the respondents had low level of knowledge of foot care, 17.5% of them had moderate knowledge while only 27.5% of them had high knowledge of foot self-care.

Figure 1. Respondents’ level of knowledge about foot self-care

Self-efficacy to practice foot ulcer preventive activities among patients

|

|

Strongly not confident |

Moderately not confident |

Confident |

Moderately confident |

Strongly confident |

|

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

|

|

I can protect my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I can examine my feet every day to check for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness, or dryness even if I'm not in pain or uncomfortable. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I can determine when to use a pumice stone to smooth corns and/or calluses on my feet. I can dry between my toes after washing my feet. I can determine when my toenails need to be clipped by a podiatrist. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

Prior to dipping my feet into the water, I may check the water's temperature. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

Even when I'm not in pain or uncomfortable, I may examine my feet daily to look for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness, or dryness. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I am able to judge when to use a pumice stone on my foot to remove calluses and/or corns. After washing my feet, I can pat dry between my toes. I am able to tell when a podiatrist is necessary to trim my toenails. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

43 (35.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I could take a look at the water's temperature before putting my feet in it. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

44 (36.7%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

If I was told to do so, I can wear shoes and socks every time I walk (includes walking indoors) |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (8.3%) |

44 (36.7%) |

0 (0%) |

|

When I go shopping for new shoes, I can choose shoes that are good for my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (8.3%) |

44 (36.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

I can call my doctor about problems with my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

44 (36.7%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

I can check the insides of my shoes for problems that can harm my feet before putting them on |

55 (45.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

11 (9.2%) |

33 (27.5%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

I can routinely apply lotion on my feet if directed to do so |

55 (45.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

11 (9.2%) |

22 (18.3%) |

21 (17.5%) |

Table 5: Measure of confidence (Self-efficacy), N=120

As shown in Table 5, 66 (55.0%), 0 (0.0%), 11 (9.2%), 32 (26.7%) and 11 (9.2%) of the participants responded that, they were strongly not confident, moderately not confident, confident, moderately confident and strongly confident respectively to each of items ‘I can protect my feet’, ‘even without pain/discomfort, I can look at my feet daily to check for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness or dryness’, ‘After washing my feet, I can dry between my toes’, ‘I can judge when my toenails need to be trimmed by a podiatrist’, ‘I can trim my toenails straight across’, and ‘I can figure out when to use a pumice stone to smooth corns and/or calluses on my feet’. Majority of the participants agreed they were strongly not confident, moderately not confident, confident, moderately confident and strongly confident respectively to item which stated, "I can test the water's temperature before putting my feet into it". Overall, the mean self-efficacy score was 28.47±18.19.

|

Behavior Item |

Response Options |

f (%) |

|

Examination & Hygiene |

||

|

How often do you examine your feet? |

Once a week |

11 (9.2) |

|

2–6 times a week |

55 (45.8) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check your shoes before you put them on? |

Once a week |

11 (9.2) |

|

2–6 times a week |

55 (45.8) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check your shoes when you take them off? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wash your feet? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check feet are dry after washing? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you dry between toes? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you use moisturizing cream on your feet? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you apply cream between toes? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Are your toenails cut? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Footwear Habits |

||

|

Do you wear unfastened slippers? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

10 (8.3) |

|

|

Never |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Do you wear sneakers? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

10 (8.3) |

|

|

Never |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes with straps, Velcro, or lace-up closures? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes with pointy toes? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you dress in mules or flip-flops? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Is it customary to break in new shoes gradually? |

Always |

22 (18.3) |

|

Most of the time |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Rarely/Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear synthetic socks (e.g., nylon)? |

Most of the time |

22 (18.3) |

|

Sometimes |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes without socks/tights? |

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

Rarely |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Often |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

How often do you replace socks/tights? |

< 4 times/week |

33 (30.3) |

|

4–6 times/week |

21 (19.3) |

|

|

Daily |

33 (30.3) |

|

|

> once/day |

22 (20.2) |

|

|