Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui 1, 2 *, Nabil Ajjel 1, Maha Mohamed Marzouk Ahmed 1,

Osama Helmi Mohammad Subih 1, Mehdi Halleb 1

1. Department of Nursing, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar.

2. Institut Universitaire de Formation des Cadres (INUFOCAD), Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

* Corresponding author: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Graduate Registered Nurse, Department of Nursing, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar. PhD Student in Education and Governance, Institut Universitaire de Formation des Cadres (INUFOCAD), Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Email: ghalgaouiabdelbasset@gmail.com

Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Nabil Ajjel, Maha Mohamed Marzouk Ahmed, Osama Helmi Mohammad Subih, Mehdi Halleb

Original article

DOI:10.32549/OPI-NSC-130

Submitted: 29 October 2025

Revised: 05 January 2026

Accepted: 06 January 2026

Published online: 09 January 2026

License: This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 (CC BY NC ND 4.0) international license.

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Job satisfaction is a key determinant of nurse retention, morale, and quality of care. Leadership styles directly shape satisfaction by influencing recognition, autonomy, and support within clinical environments. In Qatar’s multicultural nursing workforce, understanding these dynamics is critical.

Objective: This study investigated the relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC).

Method: A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 980 registered nurses recruited through simple random sampling. Data were collected using a structured online questionnaire incorporating socio-demographic data, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X), and the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire – Short Form (MSQ). Descriptive and inferential statistics, including Spearman’s correlation, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests, were employed.

Results: The sample was predominantly female (72.1%) and expatriate, with Indian (42.1%) and Filipino (33.9%) nurses forming the largest groups. Transactional leadership (mean = 2.57) was more common than transformational leadership (mean = 2.20). Overall satisfaction levels were moderate. Transformational leadership showed a strong positive correlation with both intrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.66, p < 0.001) and extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.79, p < 0.001), yielding an overall significant relationship with total job satisfaction (rho = 0.73, p < 0.001).Transactional leadership demonstrated a weak to moderate positive correlation (rho = 0.30, p < 0.001), while passive-avoidant leadership showed no meaningful association with satisfaction (rho = 0.06, p = 0.041).

Conclusion: Transformational leadership has the strongest influence on job satisfaction, while transactional and passive-avoidant styles limit long-term fulfillment. Enhancing transformational leadership at HMC may improve satisfaction, retention, and workforce stability.

Keywords: Leadership, Nurses, Job Satisfaction, Retention

INTRODUCTION

In the dynamic and demanding field of healthcare, nurses occupy a vital role. They are not merely caregivers but the backbone of healthcare institutions, providing essential treatment, compassion, and expertise to patients in need. The satisfaction of nurses is a crucial element that directly impacts their well-being, retention, and ultimately the quality of care delivered to patients.

Leadership plays a central role in shaping the experiences of nurses within healthcare organizations. Nurse managers, through their leadership styles, have the ability to empower their teams, foster a supportive work culture, and contribute to overall job satisfaction. Effective leadership can inspire motivation, strengthen commitment, and enhance the professional fulfillment of nurses. Conversely, ineffective or unsupportive leadership can create dissatisfaction, burnout, and even intentions to leave the profession, posing challenges for healthcare quality and staff retention[1,2].

Avolio and Bass have identified three primary leadership styles: transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant (laissez-faire). Transformational leaders inspire and motivate followers toward shared goals, encouraging innovation and personal growth. Transactional leaders emphasize structure, rewards, and performance management. Passive-avoidant leaders, however, tend to disengage, avoiding intervention and decision-making, often resulting in reduced productivity and workplace dissatisfaction[3,4]. Nurse managers often apply one or a combination of these styles, with varying outcomes on nurse satisfaction.

Studies conducted in Qatar and the surrounding region highlight the prevalence and influence of leadership styles in healthcare. For example, transformational leadership has been shown to be the most commonly practiced style among nursing leaders in Qatar[5]. Additionally, research in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain has demonstrated that transformational and transactional leadership approaches are positively linked to nurses’ satisfaction, commitment, and reduced turnover intentions[6,7]. These findings reinforce the importance of leadership style as a determinant of nurse satisfaction in Middle Eastern healthcare settings, including at HMC.

The relevance of this issue at HMC is further underscored by local research showing that a significant proportion of nurses and healthcare workers have reported dissatisfaction, stress, and turnover intentions, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic[8]. Such challenges highlight the pressing need to evaluate how leadership styles adopted by nurse managers influence nurses’ satisfaction within HMC.

Therefore, this study seeks to explore the perceptions of nurses regarding their managers’ leadership styles and to examine the relationship between these leadership approaches and nurses’ job satisfaction. Understanding this relationship is crucial to developing effective leadership strategies that enhance nurse satisfaction, reduce turnover, and improve the overall quality of patient care. Addressing this gap is essential to achieving Qatar’s National Health Strategy goals for workforce sustainability and excellence in healthcare delivery.

Objectives

This study aimed to describe nurses’ perceptions of their managers’ leadership styles, assess their job satisfaction levels, and examine associations between leadership approaches and satisfaction dimensions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Type and Classification of Study

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to examine the relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and nurses’ job satisfaction at HMC, Qatar.

Comparisons and Predictors of Interest

The primary focus was on comparing various nurse manager leadership styles and their respective impacts on staff nurses’ job satisfaction.

Study Duration

The study was conducted over a period of approximately four months, from November 5, 2024, to March 1, 2025.

Sample Size Justification

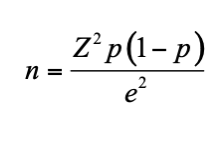

To ensure reliability and representativeness of the findings, a sample size calculation was conducted based on a population of approximately 12,000 nurses. Using a 95% confidence level and a ±3% margin of error, an estimate minimal sample size of 1067 nurses was determined to be appropriate. The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula:

where Z = 1.96, p = 0.5, e = 0.03. Since the estimate minimal sample size is large and >5% compared to the population from which it is obtained (12,000), the sample size can be reduced to 980 nurses.

The value p = 0.5 was chosen to provide the most conservative estimate and ensure adequate sample size in the absence of prior data, while a ±3% margin of error was selected to achieve high precision and reliable representativeness of the study findings.

Study Population and Setting

The study population comprised registered nurses working in various departments across Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Qatar. Participants were selected through a simple random sampling method. The sampling frame included the complete list of licensed nurses at HMC, each assigned a unique identification number. Using Microsoft Excel’s RAND function, the list was randomly ordered to facilitate unbiased selection.

To account for an anticipated non-response rate, the initial calculated sample of 980 nurses determined based on a 95% confidence level and a ±3% margin of error for a population of approximately 12,000 nurses was increased by 245, resulting in a total of 1,225 nurses being invited to participate. Questionnaires were distributed via official HMC email accounts, and 980 completed responses were obtained, forming the final study sample. This strategy ensured a representative sample across different hospitals and nursing units within HMC.

The study was carried out exclusively within HMC facilities.

Inclusion Criteria

- Registered nurses currently employed at HMC.

- Nurses who voluntarily consented to participate.

- Nurses with a minimum of six months of experience at HMC to ensure familiarity with the organizational culture and leadership practices.

Exclusion Criteria

- Nurses on leave or absent during data collection.

- Nurses in managerial or supervisory roles.

- Contract or temporary nurses.

Data Collection

Data were collected via structured online questionnaires distributed through Google Forms. The survey instruments covered the following areas:

- Socio-demographic Data

Collected information included age, gender, nationality, years of nursing experience, tenure at HMC, education level, hospital, and department. Age was categorized into three groups (≤30 years, 31–45 years, and >45 years) to reflect early, mid-, and late-career stages. Similarly, years of nursing experience and years of experience within HMC were grouped as ≤5 years, 6–15 years, and >15 years to allow meaningful comparisons between groups and ensure adequate sample sizes for statistical analysis.

- Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X)

This 45-item tool assessed leadership styles (transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire) across dimensions such as inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and contingent reward. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Frequently, if not always”) [9]. Items were grouped into their respective leadership dimensions using the MLQ scoring key. For each dimension, a mean score was calculated by summing the responses to the items composing that scale and dividing by the number of valid responses. All leadership style subscales consisted of four items each. Blank or missing responses were excluded from the calculations. Higher mean scores indicated more frequent exhibition of the corresponding leadership behaviors. Leadership dimensions were analyzed as continuous variables rather than categorizing leaders into a single leadership style.

The tool demonstrated strong reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.90.

- Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Short Form)

This 20-item scale measured job satisfaction across facets such as supervision, pay, promotion, coworkers, and communication. Responses ranged from 1 (“Not Satisfied”) to 5 (“Extremely Satisfied”)[10]. The instrument showed good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha range of 0.70 to 0.90.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

- Primary Outcomes: Nurses’ job satisfaction.

- Secondary Outcome: The relationship between nurse manager leadership styles and the three primary outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and key variables such as means, standard deviations, medians, ranges, and percentages. Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated non-normal distribution (p < 0.05). Therefore, non-parametric statistical tests were applied, including Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis H for group comparisons.

Correlation between leadership styles and job satisfaction was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) due to non-normal distribution. The statistical tests with p-value < 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS-26 software.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature of the study were explained through official internal communication channels via HMC e-mail. Participants provided electronic consent after having at least two months to review the study information before deciding to participate. Only registered nurses employed at HMC who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. No financial incentives were offered for participation.

The study was approved by the Medical Research Center (MRC) – Local Ethics Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar (Protocol No. MRC-01-24-356), with approval granted on 15/08/2024, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as well as the regulations of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), Qatar. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the study.

RESULTS

Demographic and Professional Characteristics

The study sample of 980 nurses demonstrated a pronounced gender imbalance, with females constituting nearly three-quarters of the workforce (Table 1). Marriage was the predominant status, and Indian and Filipino nationals together comprised more than three-quarters of the participants, highlighting the concentration of the workforce among specific nationalities. Age distribution indicated that the majority of nurses were mid-career professionals aged 30–45 years (67.04%), whereas younger nurses (≤30 years) formed a small minority (6.53%).

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

Frequency (n) |

Percent (%) |

Mean± SD |

|

Gender |

Male |

273 |

27.86 |

|

|

Female |

707 |

72.14 |

||

|

Marital Status |

Single |

138 |

14.08 |

|

|

Married |

820 |

83.67 |

||

|

Widowed |

8 |

0.82 |

||

|

Separated / Divorced |

14 |

1.43 |

||

|

Nationality |

Cuban |

36 |

3.67 |

|

|

Egyptian |

16 |

1.63 |

||

|

Filipino |

332 |

33.88 |

||

|

Indian |

413 |

42.14 |

||

|

Iranian |

3 |

0.31 |

||

|

Jordanian |

64 |

6.53 |

||

|

Lebanese |

5 |

0.51 |

||

|

Palestinian |

8 |

0.82 |

||

|

Somali |

3 |

0.31 |

||

|

Sudanese |

51 |

5.20 |

||

|

Tunisian |

49 |

5.00 |

||

|

Age (years) |

≤30 years |

64 |

6.53 |

40.40 ± 7.89 |

|

]30-45] |

657 |

67.04 |

||

|

> 45 |

259 |

26.43 |

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics (N=980)

Hospital and departmental distribution demonstrated a concentration of staff in a limited number of facilities and clinical areas. Hamad General Hospital employed the largest share (27.55%), followed by Rumailah (11.63%), Al Wakra (11.43%), and the Women’s Wellness & Research Center (8.16%). The Surgical and Medical departments collectively accounted for more than 65% of participants, whereas Critical Care, Emergency, and Outpatient/ Ambulatory units had smaller staff representation.

These demographic patterns suggest that the HMC nursing workforce is highly experienced and predominantly composed of expatriate professionals, highlighting the importance of culturally adaptive leadership strategies.

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

Frequency (n) |

Percent (%) |

Mean± SD |

|

Years of experience as a nurse |

≤5 years |

21 |

2.14 |

16.85 ± 7.14 |

|

]5-15] |

532 |

54.29 |

||

|

> 15 |

427 |

43.57 |

||

|

Years of experience in HMC |

≤5 years |

360 |

36.73 |

9.93 ± 7.54 |

|

]5-15] |

369 |

37.65 |

||

|

> 15 |

251 |

25.61 |

||

|

Educational background |

Diploma |

139 |

14.18 |

|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

751 |

76.63 |

||

|

Master’s degree |

90 |

9.18 |

||

|

Hospital |

Hamad General Hospital |

270 |

27.55 |

|

|

Ambulatory Care Center |

58 |

5.92 |

||

|

Qatar Rehabilitation Institute |

17 |

1.73 |

||

|

NCCCR |

19 |

1.94 |

||

|

Mental Health Service |

48 |

4.90 |

||

|

Communicable Disease Center |

15 |

1.53 |

||

|

Al Khor Hospital |

72 |

7.35 |

||

|

Rumailah Hospital |

114 |

11.63 |

||

|

Al Wakra Hospital |

112 |

11.43 |

||

|

Hazm Mebaireek General Hospital |

64 |

6.53 |

||

|

Aisha Bint Hamad Al Attiyah Hospital |

63 |

6.43 |

||

|

The Cuban Hospital |

17 |

1.73 |

||

|

Women’s Wellness and Research Center |

80 |

8.16 |

||

|

Heart Hospital |

31 |

3.16 |

||

|

Department |

Critical Care / Emergency Services |

220 |

22.45 |

|

|

Medical Department |

296 |

30.20 |

||

|

Surgical Department |

348 |

35.51 |

||

|

Outpatient (OPD) and Ambulatory Services |

116 |

11.84 |

Table 2. Professional Characteristics (N=980)

Nurse Manager Leadership Styles

The analysis of nurse manager leadership styles revealed that transactional leadership was more prominent (mean = 2.57, SD = 0.85; Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 3.12) compared to transformational leadership (mean = 2.20, SD = 1.05; Q1 = 1.55, Q3 = 3.00). This suggests that managers primarily use structured management approaches, emphasizing performance-based rewards and active monitoring (Table 3).

|

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

S D |

Median |

Q1 |

Q3 |

|

Idealized Attributes or Idealized Influence (Attributes) |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.19 |

1.14 |

2.25 |

1.50 |

3.00 |

|

Idealized Behaviors or Idealized Influence (Behaviors) |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.35 |

1.15 |

2.50 |

1.75 |

3.25 |

|

Inspirational Motivation |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.34 |

1.22 |

2.50 |

1.50 |

3.25 |

|

Intellectual Stimulation |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.21 |

1.11 |

2.25 |

1.50 |

3.00 |

|

Individual Consideration |

0.00 |

4.00 |

1.94 |

0.96 |

2.00 |

1.25 |

2.75 |

|

Transformational |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.20 |

1.05 |

2.35 |

1.55 |

3.00 |

|

Contingent Reward |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.56 |

1.05 |

2.75 |

2.00 |

3.25 |

|

Mgmt by Exception (Active) |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.58 |

0.98 |

2.75 |

2.00 |

3.25 |

|

Transactional |

0.25 |

4.00 |

2.57 |

0.85 |

2.62 |

2.00 |

3.12 |

|

Mgmt by Exception (Passive) |

0.00 |

4.00 |

1.55 |

1.01 |

1.25 |

0.75 |

2.25 |

|

Laissez-Faire |

0.00 |

4.00 |

1.43 |

1.05 |

1.25 |

0.50 |

2.25 |

|

Passive Avoidant |

0.00 |

4.00 |

1.49 |

0.97 |

1.37 |

0.75 |

2.12 |

|

Extra Effort |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.17 |

1.20 |

2.33 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

|

Effectiveness |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.25 |

1.22 |

2.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

|

Satisfaction |

0.00 |

4.00 |

2.28 |

1.31 |

2.50 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

|

Outcomes of Leadership |

0.00 |

400 |

2.23 |

1.20 |

2.42 |

1.05 |

3.16 |

Table 3. Nurse Manager Leadership Styles.

Within the transactional domain, contingent reward (mean = 2.56, SD = 1.05; Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 3.25) and management by exception active (mean = 2.58, SD = 0.98; Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 3.25) were the most utilized strategies.

Among transformational leadership subscales, idealized influence behaviors (mean = 2.35, SD = 1.15; Q1 = 1.75, Q3 = 3.25) scored highest, indicating that some leaders act as strong role models. Conversely, individual consideration (mean = 1.94, SD = 0.96; Q1 = 1.25, Q3 = 2.75) was lowest, suggesting limited mentorship or personalized support for staff.

Passive-avoidant leadership had the lowest overall scores (mean = 1.49, SD = 0.97; Q1 = 0.75, Q3 = 2.12), particularly laissez-faire leadership (mean = 1.43, SD = 1.05; Q1 = 0.50, Q3 = 2.25), showing that managers generally remain engaged and avoid ignoring decision-making responsibilities. Management by exception passive (mean = 1.55, SD = 1.01; Q1 = 0.75, Q3 = 2.25) indicated occasional reactive behaviors. Leadership outcomes were moderate, with effectiveness (mean = 2.25, SD = 1.22; Q1 = 1.00, Q3 = 3.00) and satisfaction (mean = 2.28, SD = 1.31; Q1 = 1.00, Q3 = 3.00) reflecting satisfactory performance from the staff perspective.

The dominance of transactional leadership may reflect the organizational focus on compliance and efficiency rather than on empowerment or innovation.

Nurses’ Satisfaction

The results indicate that nurses experience moderate job satisfaction across both intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions as well as in the overall satisfaction measured by the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) – Short Form. For intrinsic satisfaction, 57.55% of participants fall into the average category (Table 4), while 20.41% report low satisfaction, with a mean score of 2.93 ± 0.93 (Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 2.00). The quartile values indicate that most respondents cluster tightly around the lower end of the moderate range, suggesting limited variability in perceived intrinsic motivators. In contrast, extrinsic satisfaction shows that 57.14% of respondents are moderately satisfied, but a slightly higher percentage (22.86%) report low satisfaction, with a mean score of 2.74 ± 1.01 (Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 2.00). Similar to intrinsic satisfaction, the Q1 and Q3 values suggest that extrinsic satisfaction is concentrated at the lower boundary of moderate satisfaction, reinforcing the need for improvements in external factors such as pay and recognition.

Regarding overall satisfaction (MSQ), 71.84% of respondents are in the average category, 8.57% report low satisfaction, and 19.59% report high satisfaction, with a mean score of 2.87 ± 0.94 (Q1 = 2.00, Q3 = 2.00). The quartile distribution again shows that the majority of nurses fall at the lower end of the moderate satisfaction range. The moderate satisfaction levels indicate room for improvement, particularly in extrinsic factors such as pay and recognition.

|

|

Range |

Frequency |

Percent |

Min |

Max |

Mean±SD |

Median [Q1, Q3] |

|

Intrinsic Satisfaction |

Low Satisfaction |

200 |

20.41 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.93 (0.93) |

3.00 [2.41, 3.58] |

|

Average Satisfaction |

564 |

57.55 |

|||||

|

High Satisfaction |

216 |

22.04 |

|||||

|

Extrinsic Satisfaction |

Low Satisfaction |

224 |

22.86 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.74 (1.01) |

2.83 [2.00, 3.50] |

|

Average Satisfaction |

560 |

57.14 |

|||||

|

High Satisfaction |

196 |

20.00 |

|||||

|

General Satisfaction of MSQ |

Low level of satisfaction |

84 |

8.57 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.87 (0.94) |

2.95 [2.25, 3.55] |

|

Average level of satisfaction |

704 |

71.84 |

|||||

|

High level of satisfaction |

192 |

19.59 |

Table 4. Nurses’ Satisfaction

Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses’ Satisfaction

In Table 5, female nurses reported significantly higher job satisfaction than male nurses (mean rank: 506.43 vs 449.23, p = 0.005). Single nurses showed the highest satisfaction, followed by married and widowed nurses (550.57 vs. 473.29 vs 373.50, p = 0.006). Significant differences were observed across nationalities, with Somali nurses reporting the highest satisfaction and Cuban nurses the lowest (665.17 vs 254.44, p < 0.001). No significant differences were found by age, although nurses aged ≤30 years had slightly higher satisfaction than those >45 years and those aged 30–45 years (524.38 vs 513.45 vs 478.15, p = 0.144). Similarly, years of nursing experience showed no significant differences, but nurses with ≤5 years of experience reported higher satisfaction than those with >15 years or 5–15 years (589.64 vs 494.45 vs. 483.42, p = 0.224).

Years of experience within HMC was significantly associated with satisfaction, with nurses having >15 years reporting the highest and those with 5–15 years reporting the lowest satisfaction (537.60 vs 422.53, p < 0.001).

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

Mean Rank |

Statistic |

p-value (Test) |

|

Gender |

Male |

449.23 |

85239.5 |

0.005(MW)* |

|

Female |

506.43 |

|||

|

Marital Status |

Single |

550.57 |

10.32 |

0.006(KW)* |

|

Married |

473.29 |

|||

|

Widowed |

373.50 |

|||

|

Nationality |

Cuban |

254.44 |

35.18 |

< 0.001(KW)* |

|

Egyptian |

375.50 |

|||

|

Filipino |

494.46 |

|||

|

Indian |

502.89 |

|||

|

Iranian |

604.50 |

|||

|

Jordanian |

543.19 |

|||

|

Lebanese |

598.90 |

|||

|

Palestinian |

515.75 |

|||

|

Somali |

665.17 |

|||

|

Sudanese |

442.23 |

|||

|

Tunisian |

518.79 |

|||

|

Age (years) |

≤30 years |

524.38 |

3.87 |

0.144(KW) |

|

]30-45] |

478.15 |

|||

|

> 45 |

513.45 |

|||

|

Years of experience as a nurse |

≤5 years |

589.64 |

2.99 |

0.224(KW) |

|

]5-15] |

483.42 |

|||

|

> 15 |

494.45 |

|||

|

Years of experience in HMC

|

≤5 years |

527.33 |

34.35 |

< 0.001(KW)* |

|

]5-15] |

422.53 |

|||

|

> 15 |

537.60 |

|||

|

Educational background |

Diploma |

529.18 |

11.51 |

0.003(KW)* |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

474.27 |

|||

|

Master’s degree |

566.21 |

|||

|

Hospital |

Hamad General Hospital |

515.00 |

52.14 |

< 0.001(KW)* |

|

Al Khor Hospital |

378.97 |

|||

|

Rumailah Hospital |

503.45 |

|||

|

Al Wakra Hospital |

479.68 |

|||

|

Hazm Mebaireek General Hospital |

505.44 |

|||

|

Aisha Bint Hamad Al Attiyah Hospital |

445.29 |

|||

|

The Cuban Hospital |

280.97 |

|||

|

Women’s Wellness and Research Center |

536.80 |

|||

|

Heart Hospital |

594.37 |

|||

|

Ambulatory Care Center |

525.71 |

|||

|

Qatar Rehabilitation Institute |

607.68 |

|||

|

NCCCR |

624.71 |

|||

|

Mental Health Service |

343.33 |

|||

|

Communicable Disease Center |

501.30 |

|||

|

Department |

Critical Care / Emergency Services |

529.34 |

35.339 |

< 0.001(KW)* |

|

Medical Department |

430.85 |

|||

|

Surgical Department |

479.99 |

|||

|

Outpatient (OPD) and Ambulatory Services |

600.57 |

Note: MW = Mann–Whitney U test; KW = Kruskal–Wallis H test; *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 5. Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses’ Satisfaction.

Educational background also influenced satisfaction, with nurses holding a Master’s degree reporting the highest satisfaction, followed by diploma and Bachelor’s degree holders (566.21 vs 529.18 vs. 474.27, p = 0.003). Job satisfaction differed significantly across hospitals, with QRI reporting the highest and ABAH the lowest (624.71 vs 280.97, p < 0.001). Finally, departmental differences were significant, with Outpatient (OPD) and Ambulatory Services showing the highest satisfaction and the Medical Department the lowest (600.57 vs 430.85, p < 0.001).

Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Satisfaction

The analysis reveals distinct relationships between leadership styles and job satisfaction dimensions (Table 6).

|

Intrinsic Satisfaction |

Extrinsic Satisfaction |

Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Short Form) |

||

|

Transformational

|

Spearman Coefficient (rho) |

0.66 |

0.79 |

0.73 |

|

p-value |

< 0.001* |

< 0.001* |

< 0.001* |

|

|

Transactional

|

Spearman Coefficient (rho) |

0.27 |

0.33 |

0.30 |

|

p-value |

< 0.001* |

< 0.001* |

< 0.001* |

|

|

Passive Avoidant

|

Spearman Coefficient (rho) |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

|

p-value |

0.007* |

0.142 |

0.041* |

|

Note: *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 6. Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Satisfaction.

Transformational leadership shows the strongest positive correlations with all forms of satisfaction: intrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.66, p < 0.001), extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.79, p < 0.001), and overall job satisfaction measured by the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) (rho = 0.73, p < 0.001). This suggests that employees who perceive their leaders as inspiring, supportive, and visionary tend to experience higher satisfaction both from the work itself and from external rewards.

Transactional leadership also shows positive but more moderate correlations: intrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.27, p < 0.001), extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.33, p < 0.001), and overall satisfaction (rho = 0.30, p < 0.001). This implies that while reward-based leadership influences job satisfaction, its impact is less pronounced than that of transformational leadership, particularly affecting extrinsic satisfaction. In contrast, passive-avoidant leadership has minimal associations with job satisfaction. The correlations are very weak for intrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.08, p = 0.007) and overall satisfaction (rho = 0.065, p = 0.041), and non-significant for extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.04, p = 0.142). This indicates that passive leadership, marked by inaction and avoidance of responsibility, has little to no effect on employee satisfaction.

Overall, these findings highlight the significant role of transformational leadership in fostering job satisfaction, while transactional leadership has a moderate influence, and passive-avoidant leadership remains largely ineffective. These results confirm that transformational leadership is the most powerful predictor of nurse satisfaction, emphasizing the need for leadership development programs at HMC

DISCUSSION

Demographic and Professional Characteristics

The study sample predominantly comprised female nurses (72.14%), reflecting global trends in nursing gender distribution. The underrepresentation of males (27.86%) highlights ongoing gender disparities in the profession, which may influence workplace dynamics and care delivery. The high proportion of married participants (83.67%) suggests a stable workforce, though potential stressors related to work-life balance warrant consideration. The dominance of Indian (42.14%) and Filipino (33.88%) nationalities aligns with Qatar’s reliance on expatriate healthcare workers, raising questions about cultural adaptation and retention strategies. The mean age of 40.40 years and extensive experience (16.85 ± 7.14 years), indicate a mature, seasoned workforce. However, the low representation of nurses with ≤5 years of experience (2.14%) may signal challenges in recruiting younger professionals. The predominance of Bachelor’s degrees (76.63%) reflects standardization in nursing education, yet the limited advanced degrees (9.18%) suggests opportunities for career development. The concentration of nurses in surgical and medical departments (65.71%) underscores the demand for acute care expertise, while lower representation in specialized units (e.g., Communicable Disease Center) may reflect niche-staffing needs.

Nurse Manager Leadership Styles

The predominance of transactional leadership (mean = 2.57) over transformational styles (mean = 2.20), while passive-avoidant leadership was minimal overall (mean = 1.49) suggests a managerial focus on structured, compliance-driven approaches in this healthcare setting. The reliance on contingent rewards (mean = 2.56) and active monitoring (mean = 2.58) aligns with environments prioritizing task completion over innovation, which may reflect high-pressure clinical demands requiring strict adherence to protocols. However, the low emphasis on individual consideration (mean = 1.94) a core transformational trait indicates missed opportunities for personalized mentorship and emotional support, factors critical for nurse retention and job satisfaction. The moderate to low use of management by exception passive (mean = 1.55) suggests some leaders delay addressing issues until problems escalate, potentially eroding trust. These findings mirror studies where transactional leadership ensures baseline efficiency but fails to inspire long-term commitment [3]. The moderate effectiveness (mean = 2.25) and satisfaction (mean = 2.28) scores further underscore the limitations of overly transactional approaches in fostering intrinsic motivation.

Similar patterns have been observed in studies conducted across the Middle East. In this study, transactional leadership dominates, while other studies highlight differences between transformational and transactional leadership styles in healthcare settings. Passive-avoidant leadership remains very rare. A study conducted in Jordan found that respondents perceived transactional leadership as the most prevalent style among their nurse managers, followed by transformational leadership, with passive-avoidant leadership being the least common [11]. Conversely, two studies conducted in Saudi Arabia reported that transformational leadership was the most dominant style [12,13].

Nurses’ Satisfaction

Moderate intrinsic (mean = 2.93) and extrinsic (mean = 2.74) satisfaction scores reveal unmet needs in both personal fulfillment and external rewards. The 20.41% reporting low intrinsic satisfaction suggests gaps in professional growth opportunities, such as limited access to training or leadership roles. Extrinsic dissatisfaction (22.86% low satisfaction) may stem from inflexible schedules, inadequate compensation, or insufficient recognition issues exacerbated by transactional leadership’s focus on extrinsic rewards.

In the same regional context, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia also found generally low levels of job satisfaction [14]. In contrast, a study in a public hospital in Poland using the same Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) reported higher satisfaction scores, ranging from 3.05 to 3.43, indicating a higher overall level of job satisfaction. In that study, dimensions such as recognition, independence, and working conditions were rated more favorably, and overall satisfaction with work and life was significantly higher [15]. These differences may reflect organizational or leadership factors, such as limited development opportunities or reliance on transactional leadership in our context. Enhancing training access, recognition, and flexibility may help improve satisfaction and address these gaps.

Comparison of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Their Association with Nurses’ Satisfaction

Job satisfaction disparities highlight systemic inequities. Females reported higher satisfaction than males (p = 0.005), potentially due to alignment with societal caregiving roles or workplace inclusivity efforts. A study conducted in Poland within a similar context also found a relationship between gender and job satisfaction [15]. Single nurses (mean rank = 550.57) were more satisfied than married or widowed peers, possibly due to fewer work-life conflicts. Somali nurses (mean rank = 665.17) reported the highest satisfaction, while Tunisians (mean rank = 49) expressed profound dissatisfaction, underscoring the impact of cultural integration and institutional support. A cross‐sectional survey in Saudi Arabia found significant associations between nationality and lower job satisfaction, particularly when orientation and language support were lacking[16]. Younger nurses (≤30 years) and those with ≤5 years of experience showed higher satisfaction, suggesting optimism or alignment with early-career expectations. Nurses with >15 years at HMC were more satisfied (p < 0.001), likely due to career stability or leadership roles. Master’s-degree or more holders (mean rank = 566.21) reported greater satisfaction than diploma and bachelor nurses, emphasizing the role of education in professional fulfillment. Hospitals like QRI (mean rank = 624.71) and outpatient departments (mean rank = 600.57) scored highly, possibly due to manageable workloads or patient interaction. Addressing these variations requires culturally sensitive policies and career development pathways. A meta‐analysis study reported that the negative impact of nurse burnout on outcomes was not moderated by age, sex, or experience implying demographic factors alone may not drive overall well-being in broader contexts[17].

Correlation between Nurse Manager Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Satisfaction

Transformational leadership’s exceptionally strong correlation with overall satisfaction (rho = 0.73, p < 0.001), and especially extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.79, p < 0.001), is consistent with Specchia et al.’s systematic review of 12 studies, which identified 9 out of 9 studies showing a positive relationship between transformational behaviors and nurses’ job satisfaction[18]. Gebreheat et al.’s integrative review similarly found that 17 out of 17 studies reported a positive impact of transformational leadership on nurses’ job satisfaction[19]. That It is likely due to its emphasis on recognition and shared goals.

Conversely, transactional leadership’s moderate correlation with overall satisfaction (rho = 0.30, p < 0.001), intrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.27, p < 0.001) and extrinsic satisfaction (rho = 0.33, p < 0.001) mirrors Specchia et al.’s finding that four studies observed positive correlations, three found no significant relationship, and one even reported a negative link between transactional behaviors and satisfaction[18]. While contingent rewards can satisfy baseline needs reflected in our moderate extrinsic coefficient, they lack the deeper emotional resonance necessary to engender long-term commitment or intrinsic fulfillment.

Finally, passive-avoidant leadership exhibited negligible associations with all satisfaction metrics (overall rho = 0.06, p = 0.041; intrinsic rho = 0.08, p = 0.007; extrinsic rho = 0.04, p = 0.142), reinforcing Specchia et al.’s observation that three studies documented a negative correlation between passive-avoidant behaviors and nurse satisfaction[18]. When managers abdicate decision-making and fail to provide feedback or recognition, role ambiguity and diminished trust arise, eroding both extrinsic perceptions (no rewards or performance guidance) and intrinsic drivers (no inspiration or support).

Recommendations

The study underscores the critical importance of nurse manager leadership styles in shaping nurses’ job satisfaction at HMC. Based on the findings, several recommendations are proposed to enhance satisfaction and overall workplace well-being.

Firstly, HMC should invest in comprehensive leadership training programs that prioritize transformational leadership development. Such programs should focus on building leaders’ ability to inspire, empower, and communicate effectively with their teams. Emphasizing qualities such as empathy, recognition, and individualized consideration can strengthen nurses’ intrinsic motivation and sense of belonging, which are key determinants of satisfaction.

Secondly, the organization should foster open communication and participatory decision-making. When nurses are given opportunities to contribute to clinical and administrative decisions, their sense of value and autonomy increases two crucial components of job satisfaction. Leadership practices should therefore promote a culture of inclusion, transparency, and trust across all nursing departments.

In addition, regular satisfaction assessments should be integrated into the organization’s quality improvement framework to monitor workforce morale and identify emerging concerns early. Findings from these assessments can inform policy adjustments, recognition systems, and workload management strategies. Finally, HMC should establish mentorship and peer-support programs where experienced leaders and senior nurses can provide guidance and career support, further enhancing job satisfaction and retention among younger or less experienced staff.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is characterized by several notable strengths that enhance its credibility and contribution to nursing leadership research. A major strength lies in its large and diverse sample (N = 980), which ensures representativeness across multiple hospitals and departments within HMC. The use of validated instruments, including the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X) for assessing leadership and the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) – Short Form for measuring job satisfaction, ensures psychometric reliability and international comparability.

Furthermore, the study employs rigorous statistical techniques such as Spearman’s correlation, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests to analyze associations between leadership styles and satisfaction outcomes. This comprehensive analytical framework provides robust evidence of the differential effects of transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership on satisfaction levels. Finally, by situating the research within Qatar’s multicultural healthcare context, the study contributes original insights into how leadership behaviors influence satisfaction in a diverse, expatriate workforce a perspective that is often underrepresented in global nursing literature.

Despite its valuable findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, meaning that while correlations between leadership styles and satisfaction are established, it cannot be conclusively stated that leadership style directly causes changes in satisfaction levels. Longitudinal studies would be needed to track the evolution of satisfaction over time in response to leadership interventions. Additionally, the use of self-administered questionnaires introduces potential response bias, as participants may have provided socially desirable answers rather than fully objective reflections of their experiences. Common-method bias may also have occurred because both leadership styles and job satisfaction were measured through self-report instruments administered in the same session. The homogeneity of the sample, composed largely of expatriate nurses, limits the generalizability of results to settings with different cultural or workforce compositions. Furthermore, the linguistic and cultural diversity of participants may have affected interpretation or understanding of questionnaire items. The study was conducted exclusively at HMC, meaning institutional factors such as policies, resources, or management structures may have influenced outcomes. Finally, there was limited control for potential confounders, as unmeasured factors such as workload, unit-specific culture, or individual personality traits may also have impacted job satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that nurse manager leadership styles significantly influence nurses’ job satisfaction at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC). Transformational leadership emerged as the strongest positive predictor of intrinsic, extrinsic, and overall job satisfaction, suggesting that leaders who inspire, support, and engage their staff foster higher levels of professional fulfillment. Transactional leadership was associated with moderate positive effects, primarily on extrinsic satisfaction, while passive-avoidant leadership showed minimal or negligible impact on all satisfaction dimensions.

The study also identified significant variations in job satisfaction across hospitals, departments, nationalities, and educational levels, highlighting the role of organizational context and workforce diversity in shaping nurses’ experiences. These findings suggest that targeted interventions promoting transformational leadership behaviors such as mentorship, recognition, and participatory decision-making may enhance nurse satisfaction, retention, and overall workforce stability at HMC.

However, this study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences, and reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias and common-method bias. Additionally, linguistic and cultural differences among participants may have influenced responses. Therefore, while the results provide valuable insights for HMC, their generalizability to other healthcare settings is limited, and further research using longitudinal or multi-site designs is recommended.

Local Ethics Committee approval

The study was approved by the Medical Research Center (MRC) – Local Ethics Committee of Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar (Protocol No. MRC-01-24-356), with approval granted on 15/08/2024, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as well as the regulations of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), Qatar. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout the study.

Conflicts of interest

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards. All participants provided informed consent. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

This research received funding from the Medical Research Center at HMC.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui

Data collection: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui

Data analysis and interpretation: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui

Drafting of the manuscript: all authors

Critical revision of the manuscript: Abdelbasset Ghalgaoui, Nabil Ajjel

Final approval: all authors

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of Hamad Medical Corporation for their collaboration.

REFERENCES

- 1. Çamveren H, Arslan Yürümezoğlu H, Kocaman G. Why do young nurses leave their organization? A qualitative descriptive study. International Nursing Review. 2020;67:519–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12633

- 2. Labrague LJ, Nwafor CE, Tsaras K. Influence of toxic and transformational leadership practices on nurses’ job satisfaction, job stress, absenteeism and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28:1104–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13053

- 3. Avolio B. Full Range Leadership Development. 2nd edition. Los Angeles, Calif London: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2010.

- 4. Avolio BJ, Bass BM, editors. Developing Potential Across a Full Range of Leadership TM: Cases on Transactional and Transformational Leadership. New York: Psychology Press; 2001. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410603975

- 5. Al-Thawabiya A, Singh K, Al-Lenjawi BA, Alomari A. Leadership styles and transformational leadership skills among nurse leaders in Qatar, a cross-sectional study. Nursing Open. 2023;10:3440–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1636

- 6. AL-Dossary RN. Leadership Style, Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment Among Nurses in Saudi Arabian Hospitals. Journal of Healthcare Leadership. Dove Medical Press; 2022;14:71–81. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S365526

- 7. Pattali S, Sankar JP, Al Qahtani H, Menon N, Faizal S. Effect of leadership styles on turnover intention among staff nurses in private hospitals: the moderating effect of perceived organizational support. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10674-0

- 8. Nashwan AJ, Abujaber AA, Villar RC, Nazarene A, Al-Jabry MM, Fradelos EC. Comparing the Impact of COVID-19 on Nurses’ Turnover Intentions before and during the Pandemic in Qatar. Journal of Personalized Medicine. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021;11:456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11060456

- 9. Avolio BJ, Bass BM. Multifactor leadership questionnaire: manual and sample set. Third edition. Place of publication not identified: Mind Garden, Inc.; 2004.

- 10. Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW, Lofquist LH. Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire–short form. Educational and Psychological Measurement [Internet]. 1977 [cited 2025 July 1]; https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft08880-000. Accessed 1 July 2025

- 11. Suliman M, Aljezawi M, Almansi S, Musa A, Alazam M, Ta’an WF. Effect of nurse managers’ leadership styles on predicted nurse turnover. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2020;27:20–5. https://doi.org/10.7748/nm.2020.e1956

- 12. Areej Mohammed Asiri, Sabah Mahmoud Mahran, Naglaa Abdelaziz Elseesy. A study of staff nurses’ perceptions of nursing leadership styles and work engagement levels in Saudi general hospitals. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences. IASE; 2023;10:55–61. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2023.01.008

- 13. Alluhaybi A, Usher K, Durkin J, Wilson A. Clinical nurse managers’ leadership styles and staff nurses’ work engagement in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2024;19:e0296082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296082

- 14. Al Bazroun MI, Aljarameez F, Alhamza R, Ahmed GY, Alhybah F, Al Mutair A. Factors influencing job satisfaction and anticipated turnover among intensive care nurses in Saudi Arabia. British Journal of Healthcare Management. Mark Allen Group; 2023;29:1–10. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2021.0146

- 15. Tomaszewska K, Kowalczuk K, Majchrowicz B, Kłos A, Kalita K. Areas of professional life and job satisfaction of nurses. Front Public Health [Internet]. Frontiers; 2024 [cited 2025 May 13];12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1370052

- 16. Almansour H, Gobbi M, Prichard J, Ewings S. The association between nationality and nurse job satisfaction in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67:420–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12613

- 17. Li LZ, Yang P, Singer SJ, Pfeffer J, Mathur MB, Shanafelt T. Nurse Burnout and Patient Safety, Satisfaction, and Quality of Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2443059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43059

- 18. Specchia ML, Cozzolino MR, Carini E, Di Pilla A, Galletti C, Ricciardi W, et al. Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Results of a Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021;18:1552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041552

- 19. Gebreheat G, Teame H, Costa EI. The Impact of Transformational Leadership Style on Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: An Integrative Review. SAGE Open Nursing. SAGE Publications Inc; 2023;9:23779608231197428. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608231197428