Oseni Rukayat Ejide ¹, Emmanson Emmanson ²*, Kolawole Ifeoluwapo ¹,

Adejumo Prisca1, Obilor Helen3

- Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

- Department of Human Anatomy, University of Cross River State, Nigeria

- School of Nursing, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Emmanson Emmanson, Department of Human Anatomy, University of Cross River State, Nigeria. Email: emmansonemmanson35@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7285-7574

Oseni Rukayat Ejide, Emmanson Emmanson, Kolawole Ifeoluwapo, Adejumo Prisca, Obilor Helen

Original article

DOI:10.32549/OPI-NSC-129

Submitted: 16 October 2025

Revised: 17 December 2025

Accepted: 22 December 2025

Published online: 09 January 2026

License: This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 (CC BY NC ND 4.0) international license.

Cite this article

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The increasing prevalence of diabetes is a global public health concern, with foot ulcer prevention techniques, low self-care knowledge, and a lack of confidence contributing to complications like foot ulcers.

Methods: This cross-sectional study, conducted between January and December 2022, evaluated foot self-care knowledge, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviors among individuals with diabetes attending public tertiary hospitals in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Data from randomly selected 120 out-patients was collected using a multidimensional questionnaire, and multiple regression analysis was used to assess associations between variables.

Results: It was found that participants’ mean age was 44.8±14.65 years. Majority (58.3%) of them did not attend foot self-care education classes and had received a type-2 diabetes diagnosis within the previous 24 months. Many of the patients had low knowledge of foot self-care (55%), low self-care efficacy (55%) and poor self-care behavior (55%). Poor self-care behavior was predicted by low efficaciousness (p<0.0001) and low knowledge of foot self-care (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: The study concluded that the extent of knowledge significantly influenced self-care behaviors and the efficacy of foot self-care in averting diabetic foot ulcers. Improving these behaviors requires teaching appropriate knowledge through hands-on self-care treatments and gaining support from policymakers for its sustainability.

Keywords: Diabetes Foot Ulcer, Self-Care Knowledge, Efficacy, Behavior, Confidence.

INTRODUCTION

With an increasing prevalence, diabetes mellitus has become a global public health concern [1]. It raises mortality, illness, and medical expenses [1,2]. There are 537 million adults (20–79 years old) worldwide with diabetes as reported by International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [1]. Conversely, by 2060, the incidence of diabetes is expected to increase to 700% for type II and 65% for type I, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [3]. Additionally, diabetes is thought to be the cause of 6.7 million fatalities annually [1], with 1.5 million of those deaths occurring primarily in low- and middle-income nations [4].

According to IDF data from 2021, 1 in 22 adult Africans has diabetes, and 54% of Africans have diabetes but have not been diagnosed [1]. In Nigeria, the prevalence of diabetes rose from 2.2% in 1997 to over 6% in 2015, a more than 100% increase, according to World Health Organization (WHO) [5]. The IDF stated that the sub-Saharan region had the greatest estimated prevalence of diabetes, at 3,623,500 (3.7%). The prevalence rates of diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) in Nigeria vary from 11% to 32%, according to Ugwu et al. [6]. The rising rate of diabetes in Nigeria has been mostly linked to demographic shifts, including urbanization, the adoption of unsafe habits, poor diets that include sugar-sweetened beverages, inactivity, and dangerous alcohol and tobacco use [5,6]. This has also led to complications such as diabetic foot ulcers. This necessitates investigating the level of knowledge of people with diabetes mellitus (PWDM) on foot ulcer preventive self-care activities in selected hospitals in Abeokuta.

Millions of individuals worldwide are impacted by the dangerous side effect of diabetes called diabetic foot ulcers. It is lethal and can cause gangrene, infection, ischemia problems, neuropathy, macrovascular disease, and microvascular damage. According to Robles et al. [7], DFU is a challenging, expensive, and chronic health problem that increases morbidity and death. According to Oliver and Mutlouglu [8], ulcers are typically persistent and can occur in inpatient as well as outpatient environments. An array of variables, such as male gender, diabetes for over a decade, the advanced age of the patients, obesity, dry skin, insufficient circulation, underpinning nerve damage, callus formation, foot defects, improper foot hygiene, and poorly fitting shoes, are linked to the development of DFU, according to Khan, Khan, & Farooqui [9] and Oliver & Mutlouglu, [8]. Despite being controllable through education, it is the most costly and fatal event related with lower extremity amputation (LEA) and frequently associated with high morbidity and death [6]. Families and societies are consequently forced to bear a greater financial burden [10,11]. Other adverse effects include poor quality-of-life [12, 13]. In light of these burdens, it is important to assess how confident PWDM are in their ability to avoid foot ulcers in the selected hospitals. Therefore, this study assumes there is no significant association between efficacy and behavior of PWDM.

According to Sari et al. [14], poor foot self-care is the main factor contributing to DFU, while appropriate foot self-care can cut the risk of DFU, hospital stays, and amputations by 50%. Client-focused education on self-efficacy in FSC practices should be promoted in a time- and cost-effective manner, as continuous physician supervision is not always possible [15]. For this reason, Adeyemi et al. [16] proposed that appropriate foot care methods and patient education can avoid or lower the risk for DFU in the interim. Previous studies [9,14,17,18] revealed low to moderate foot care practice, inadequate understanding of DFU, and attitudes toward foot care prevention. People with diabetes mellitus in Sub-Saharan Africa also showed fair but insufficient awareness of diabetic foot care [19]; this is comparable to what is available in other parts of the world. Research on effective FSC behavior is still limited, and incidence of DFU, limb loss, and DFU-related premature death have increased in Nigeria. Similar to what was found by Ojewale, Okoye, and Ani [20], their study on FSC behavior and self-efficacy among PWDM in the University College Hospital, Nigeria, revealed a scarcity of investigations. Consequently, research on PWDM self-care knowledge, efficacy, and behavior is crucial. It is therefore important to explore the foot self-care behavior of PWDM in selected hospitals. In line with this, the study tested the hypothesis that there is no significant association between age, gender, educational status and behavior of FSC among PWDM, and that there is no significant association between knowledge of FSC and the behavior of PWDM. Thus, with the goal to prevent foot ulcers, this study assessed PWDM’s self-care knowledge, efficacy, and behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study which assessed the FSC knowledge, self-care efficacy and behavior of PWDM toward DFU prevention in Federal Medical Hospital (FMC), and State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta, Nigeria, between January and December 2022.

Target population

This included PWDM (type 1 and 2) in the selected hospitals.

Study population

PWDM who attended outpatient clinics, who were estimated to be 200 monthly in FMC, and 120 monthly in the State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta, respectively.

Inclusion criteria

Adult PWDM male and female aged 18 years and above managed for at least three months, that attended OPD clinic of FMC and State Hospital, Ijaiye, Abeokuta and gave consent to participate were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

PWDM with existing DFU, those critically ill, and those on admission were excluded from the study.

Sample size estimation

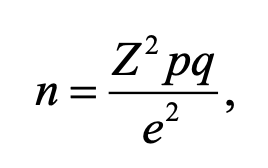

The minimum sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for estimating proportions in large populations:

where:

n0 = initial sample size, Z = standard normal deviation at 95% confidence (1.96), p = estimated proportion of the population with the attribute, q = 1 – p, e = desired margin of error.

Since no prior prevalence estimate of foot-care knowledge among individuals with diabetes in Abeokuta was available, the study used p = 50%. This value is conventionally used when there is insufficient prior data, as it maximizes sample size and increases precision. The margin of error was set at e = 10%. Based on previous values the estimated sample size is:

Additionally, a 20% attrition rate (AR) was included:

![]()

Thus, the final sample size used in this study was 120. Particularly, we adopted a relatively large margin of error (e=10%) and an attrition rate of 20%, as this is an explorative study.

Sampling technique

Two out of the three hospitals in Abeokuta; Federal Medical Center, Abeokuta and State Hospital, Ijaiye were selected using random sampling technique. A total of 120 participants were later recruited from the 2 hospitals.

Instrument for data collection

Data was obtained from respondents using structured and validated questionnaires, the questionnaire was in three sections. Section A addressed demographic data and knowledge of FSC. Section B assessed FSC behavior activities using a validated 26-item self-report tool adapted form of Nottingham Assessment of Functional Foot-care (NAFFS) [21]. While section C addressed the question on foot care efficacy using an adapted 12-item Foot Care Confidence Scale (FCCS) by Sloan Helen L. (2002) [22].

Validity of the instrument

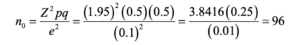

The instrument was subjected to face and construct validity by thorough scrutiny by the researcher’s supervisor and expert clinician caring for PWDM and DFU. The multidimensional validated questionnaire containing sections on FCCS and NAFFS was subjected to forward and backward translation to Yoruba and English to ensure their validity. The items in each section of the instrument were further subjected to content validity testing by submitting the instrument to five experts and using Lawshe’s formula to ensure the content validity ratio (CVR) for each item in each section of the instrument, resulting in the content validity index (CVI) for each section. According to Ayre and Sally (2013) [23], the CVR (content validity ratio) proposed by Lawshe (1975) [24] is a linear transformation of a proportional level of agreement on how many “experts” within a panel rate an item “essential” calculated in the following way:

CVR is the content validity ratio, ne is the number of panel members indicating an item “essential,” and N is the number of panel members.Just like r, CVR ranges between -1 through 0 to +1.

The closer to +1 is CVR for an item; the more valid is the item in the scale while CVR values closer to 0 imply lack of content validity. However, CVI is computed by dividing sum of CVR values by the total number of items. CVI is interpreted for the scale the same way CVR values are interpreted for the items. Table 1 displayed the CVIs for the relevant sections of the multidimensional instrument:

|

Instrument |

Number of Items |

Content Validity Index (CVI) |

Comment |

|

Foot Self-care Knowledge scale |

7 |

0.84 |

Valid |

|

FCCS |

12 |

0.76 |

Valid |

|

NAFFS |

26 |

0.86 |

Valid |

Table 1. Validity table

Reliability of the instrument

The reliability of the knowledge part of the questionnaire in section A was established using the Kuder Richardson formula- 20, KR20 conducted on SPSS Version 23 because of the dichotomous nature of the items in the section of the multidimensional instrument. Though the other 2 validated instruments, FCCS and NAFFS reportedly had Cronbach’s alpha reliability indices of 0.92 and 0.91 respectively, but all these instruments were revalidated by administering them on a sample of 30 respondents similar to but entirely different from those recruited for the main study. The reliability index obtained for the instruments was > 0.9 (Table 2).

|

Instrument |

Number of items |

Cronbach Alpha/KR20 |

Comment |

|

Foot Self-care Knowledge scale |

7 |

0.972 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

|

FCCS |

12 |

0.996 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

|

NAFFS |

26 |

0.997 |

Sufficiently Reliable |

Table 2. Reliability indices for the variables in the multidimensional instrument

Method of data collection

After gaining approval from the two institutions’ ethical committee, the individual’s informed consent, and permission from the head of the OPD at both, the instruments for data collection were given to study participants on clinic days over the course of four months (July to October, 2023), two research assistants attended a two-day training session where they learned about the objectives of the study, the content of foot care and DFU prevention guidelines/standards, FSC behavior and self-efficacy tools, and how to distribute the questionnaires. They were selected from among the registered nurses who care for patients with diabetes and DFU at Sacred Heart Hospital, Lantoro. Targeting their clinic hours on Mondays and Wednesdays, the study settings (FMC and State Hospital, Ijaye, respectively) were visited in the morning. As soon as the surveys were completed, they were gathered. People who were illiterate were helped to complete the surveys by having them translated into their native tongue.

Method of data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables.

Responses to attitudinal or perception-based questions were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree). Where applicable, composite scores were computed, and the scale reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Inferential statistics, including chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t-tests or ANOVA for comparing group means, were applied where appropriate.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data were entered and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty questionnaires were administered to the respondents, same received and used for analysis.

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

Mean |

SD |

|

Age (years) |

21–30 |

28 (23.3) |

||

|

31–40 |

24 (20.0) |

|||

|

41–50 |

21 (17.5) |

|||

|

51–60 |

26 (21.7) |

44.8 |

14.65 |

|

|

61–70 |

17 (14.2) |

|||

|

>70 |

4 (3.3) |

|||

|

Gender ᵃ |

Female |

85 (70.8) |

1.29 |

0.46 |

|

Male |

35 (29.2) |

|||

|

Marital status ᵇ |

Single |

30 (25.0) |

2.13 |

0.90 |

|

Married |

55 (45.8) |

|||

|

Separated/Divorced |

24 (20.0) |

|||

|

Widowed |

11 (9.2) |

|||

|

Educational status ᶜ |

No formal education |

28 (23.3) |

2.55 |

1.13 |

|

Primary |

31 (25.8) |

|||

|

Secondary |

28 (23.3) |

|||

|

Tertiary |

33 (27.5) |

|||

|

Occupation ᵈ |

Unemployed |

28 (23.3) |

2.53 |

1.08 |

|

Farming |

28 (23.3) |

|||

|

Trading |

37 (30.8) |

|||

|

Civil servant |

27 (22.5) |

|||

|

Type of diabetes ᵉ |

Type 1 |

50 (41.7) |

1.58 |

0.50 |

|

Type 2 |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Duration since diagnosis ᶠ |

1–24 months |

87 (72.5) |

1.47 |

0.87 |

|

25–48 months |

17 (14.2) |

|||

|

49–72 months |

9 (7.5) |

|||

|

>72 months |

7 (5.8) |

|||

|

Previous foot–care education ᵍ |

Yes |

50 (41.7) |

1.58 |

0.50 |

|

No |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Foot-care frequency ʰ |

Once a week |

16 (13.3) |

2.75 |

1.59 |

|

2–6 times/week |

22 (18.3) |

|||

|

Once a day |

8 (6.7) |

|||

|

>1 time/day |

4 (3.3) |

|||

|

Not applicable |

70 (58.3) |

|||

|

Knowledge of foot care ⁱ |

No idea |

72 (60.0) |

0.48 |

0.65 |

|

Moderate idea |

38 (31.7) |

|||

|

Expert idea |

10 (8.3) |

|||

|

Performs foot care independently ʲ |

Yes |

87 (72.5) |

1.28 |

0.45 |

|

No |

33 (27.5) |

|||

|

**If No, who helps? **ᵏ |

Family |

31 (25.8) |

2.02 |

0.98 |

|

Friends |

2 (1.7) |

|||

|

Not applicable |

87 (72.5) |

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of 120 respondents (Source: Field survey, 2023)

Table 3 showed the demographic distribution of the respondents. The majority 28 (23.1%) of them are in the age group of 21-30 years, while the 4 (3.3%) that were above 70 years were the least in the distribution with the mean age of 44.8±14.65 years. About three-quarters 85 (70.8%) are female, while 35 (29.2%) are male. The majority were married, 55 (45.8%), and 30 (25%) are single. Most of the respondents had higher education 33 (27.5%), while both illiterates and secondary school completers were 28 (23.3%), respectively. Traders were more than other categories at 37 (30.8%) followed by civil servants at 27 (22.5%).

As shown further in Table 3, more than half 70 (58.3%) of the respondents had T2DM with majority 87 (72.5%) diagnosed within the past 24 months. Findings also revealed that 50 (41.7%) of the respondents had prior attendance at FSC education while 70 (58.3%) had no such experience. A few, 16 (13.3%), 22 (18.3%), 8 (6.7%) and 4 (3.3%) of the participants attended once a month, every other month, whenever chanced, and when reminded respectively, while this was not applicable to 70 (58.3%) of them. The majority, 72 (60.0%) of the participants had no idea know what foot care is, 38 (31.7%) had moderate idea while 10 (8.3%) claimed to have expertise idea. Finally, 87 (72.5%) performed foot care by themselves while 33 (27.5%) did not.

Respondents’ knowledge of foot self-care

|

Item |

No |

Yes |

|

|

People with diabetes should check their feet at least once a day |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should inspect their toes, nails, and cut it straight |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

The feet should be washed, and lotion applied to moisturize them |

77(64.2%) |

43(35.8%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should warm their feet with lantern |

66(55%) |

54(45%) |

|

|

Before putting on shoes, people with diabetes should inspect the interior of them |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

|

|

Foot corn/callus should be removed with razor blade |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

|

|

People with diabetes should wear shoes that are not too tight |

76(63.3%) |

44(36.7%) |

Table 4. Knowledge of 120 respondents on foot self-care (Source: Field survey, 2023)

From table 4 the majority 77 (64.2%) of the participants declined that, PWDM should check their foot once daily, inspect their toes, nails, and cut it straight and the feet should be washed, and lotion applied to moisturize them. A little above half 66 (55.0%) disagreed with the statement that PWDM should warm their feet with lantern. Additionally, 44 (36.7%) of the respondents indicated that PWDM should wear shoes that are not too tight, remove corns and calluses from their feet with a razor blade, and check the inside of their shoes before wearing them.

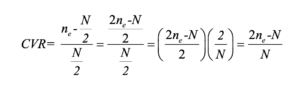

Summary of respondents’ knowledge about foot self-care

Overall, the mean knowledge score was 9.63+3.08. As shown in Figure 1, 55% of the respondents had low level of knowledge of foot care, 17.5% of them had moderate knowledge while only 27.5% of them had high knowledge of foot self-care.

Figure 1. Respondents’ level of knowledge about foot self-care

Self-efficacy to practice foot ulcer preventive activities among patients

|

|

Strongly not confident |

Moderately not confident |

Confident |

Moderately confident |

Strongly confident |

|

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

f (%) |

|

|

I can protect my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I can examine my feet every day to check for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness, or dryness even if I’m not in pain or uncomfortable. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I can determine when to use a pumice stone to smooth corns and/or calluses on my feet. I can dry between my toes after washing my feet. I can determine when my toenails need to be clipped by a podiatrist. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

Prior to dipping my feet into the water, I may check the water’s temperature. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

Even when I’m not in pain or uncomfortable, I may examine my feet daily to look for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness, or dryness. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

11 (9.2%) |

32 (26.7%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I am able to judge when to use a pumice stone on my foot to remove calluses and/or corns. After washing my feet, I can pat dry between my toes. I am able to tell when a podiatrist is necessary to trim my toenails. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

43 (35.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

|

I could take a look at the water’s temperature before putting my feet in it. |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

44 (36.7%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

If I was told to do so, I can wear shoes and socks every time I walk (includes walking indoors) |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (8.3%) |

44 (36.7%) |

0 (0%) |

|

When I go shopping for new shoes, I can choose shoes that are good for my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

10 (8.3%) |

44 (36.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

I can call my doctor about problems with my feet |

66 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

44 (36.7%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

I can check the insides of my shoes for problems that can harm my feet before putting them on |

55 (45.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

11 (9.2%) |

33 (27.5%) |

10 (8.3%) |

|

I can routinely apply lotion on my feet if directed to do so |

55 (45.8%) |

11 (9.2%) |

11 (9.2%) |

22 (18.3%) |

21 (17.5%) |

Table 5: Measure of confidence (Self-efficacy), N=120

As shown in Table 5, 66 (55.0%), 0 (0.0%), 11 (9.2%), 32 (26.7%) and 11 (9.2%) of the participants responded that, they were strongly not confident, moderately not confident, confident, moderately confident and strongly confident respectively to each of items ‘I can protect my feet’, ‘even without pain/discomfort, I can look at my feet daily to check for cuts, scratches, blisters, redness or dryness’, ‘After washing my feet, I can dry between my toes’, ‘I can judge when my toenails need to be trimmed by a podiatrist’, ‘I can trim my toenails straight across’, and ‘I can figure out when to use a pumice stone to smooth corns and/or calluses on my feet’. Majority of the participants agreed they were strongly not confident, moderately not confident, confident, moderately confident and strongly confident respectively to item which stated, “I can test the water’s temperature before putting my feet into it”. Overall, the mean self-efficacy score was 28.47±18.19.

|

Behavior Item |

Response Options |

f (%) |

|

Examination & Hygiene |

||

|

How often do you examine your feet? |

Once a week |

11 (9.2) |

|

2–6 times a week |

55 (45.8) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check your shoes before you put them on? |

Once a week |

11 (9.2) |

|

2–6 times a week |

55 (45.8) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check your shoes when you take them off? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wash your feet? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you check feet are dry after washing? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you dry between toes? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you use moisturizing cream on your feet? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you apply cream between toes? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Are your toenails cut? |

Once a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

2–6 times a week |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Once a day |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

More than once a day |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Footwear Habits |

||

|

Do you wear unfastened slippers? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

10 (8.3) |

|

|

Never |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Do you wear sneakers? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

10 (8.3) |

|

|

Never |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes with straps, Velcro, or lace-up closures? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes with pointy toes? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you dress in mules or flip-flops? |

Most of the time |

33 (27.5) |

|

Sometimes |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Is it customary to break in new shoes gradually? |

Always |

22 (18.3) |

|

Most of the time |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Rarely/Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear synthetic socks (e.g., nylon)? |

Most of the time |

22 (18.3) |

|

Sometimes |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Do you wear shoes without socks/tights? |

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

Rarely |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Often |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

How often do you replace socks/tights? |

< 4 times/week |

33 (30.3) |

|

4–6 times/week |

21 (19.3) |

|

|

Daily |

33 (30.3) |

|

|

> once/day |

22 (20.2) |

|

|

Barefoot Practices & First Aid |

||

|

Do you go barefoot at home? |

Often |

11 (9.2) |

|

Sometimes |

55 (45.8) |

|

|

Rarely |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Never |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

Are you barefoot outside? |

Often |

22 (18.3) |

|

Sometimes |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Rarely |

32 (26.7) |

|

|

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

|

Do you use a hot water bottle in bed? |

Often |

22 (18.3) |

|

Sometimes |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Rarely |

32 (26.7) |

|

|

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

|

For corns, do you use home treatments (e.g., plasters)? |

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

Rarely |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Often |

33 (27.5) |

|

|

For blisters, do you use a dry dressing? |

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

Rarely |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

10 (8.3) |

|

|

Often |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

For cuts/grazes/burns, do you use a dry dressing? |

Never |

22 (18.3) |

|

Rarely |

44 (36.7) |

|

|

Sometimes |

21 (17.5) |

|

|

Often |

33 (27.5) |

Table 6. Respondents’ foot self-care behavior/activities, N=120.

As shown in Table 6, 11 (9.2%), 55 (45.8%), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) consented that, they examined their feet and check their shoes before they put them on once a week, 2 – 6 times a week, once a day and more than once a day respectively. Also, 33 (27.5%), 33 (27.5%), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) responded once a week, 2 – 6 times a week, once a day and more than once a day respectively to each of items; “Do you wash your feet?” “Do you check that your feet are dry after washing?” “Do you dry between your toes?” “Do you use moisturizing cream on your feet?” “Do you use moisturizing cream between your toes?” and “Are your toenails cut?” – for each item, 33 (27.5%), 33 (27.5%), 10 (8.3%), and 44 (36.7%) of the participants gave their response most of the time, occasionally, seldom, and never, respectively. For questions on “Do you wear trainers?” and “Do you wear slippers without fastenings?” – 33 (27.5%), 21 (17.5%), 33 (27.5%), and 33 (27.5%) of the participants answered each item most of the time, seldom, infrequently, and never, respectively.

For the question, ‘Do you break in new shoes gradually?’, 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) of the subjects responded always, most of the time, sometimes and rarely/never respectively. Similarly, 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) responded most of the time, sometimes, rarely and never respectively to “Do you wear artificial fiber (e.g., nylon) socks. The response pattern was also 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) implying never, rarely, sometimes and often respectively for question ‘Do you wear shoes without socks/stockings/tights?’ ‘Do you change your socks/stockings/tights?’ got the response pattern, 22 (20.2%), 33 (30.3%), 21 (19.3%) and 33 (30.3%) implying more than once a day, daily, 4-6 times a week and less than 4 times a week respectively for a total of 109 responses for the item.

Items ‘Do you walk around the house in bare feet?’ and ‘Do you walk outside in bare feet?’ turned in the response pattern, 11 (9.2%), 55 (45.8), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) to denote often, sometime, rarely and never respectively. Also, 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7%), 32 (26.7%) and 22 (18.3%) gave the responses, often, sometime, rarely and never respectively to item “Do you use a hot water bottle in bed?”, item “Do you place your feet close to the flames?” and “Do you place your feet on a radiator?”. For item ‘Do you use corn remedies/ corn plasters/paints when you get a corn?’ and item ‘Do you put a dry dressing on a graze, cut or burn when you get one?’, 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7%), 21 (17.5%) and 33 (27.5%) of the participants responded, never, rarely, sometimes and often respectively to each of the items. On the other hand, the responses to the question, “Do you put a dry dressing on a blister when you get one?” were as follows: 22 (18.3%), 44 (36.7%), 10 (8.3%), and 44 (36.7%). Whereas the mean of 39.34±27.57 was obtained for respondents’ foot self-care behavior.

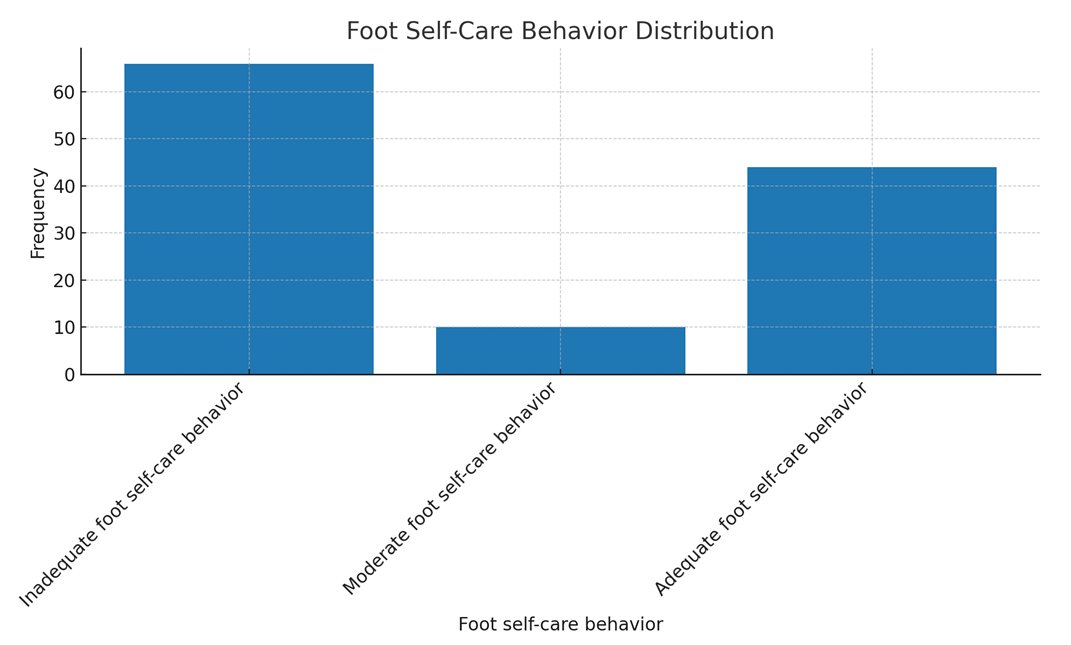

Figure 2. Respondents’ foot self-care behavior

As shown in Figure 2, 66(55%) of them had inadequate foot self-care behavior, only 10 (8.3%) of them had moderate foot self-care behavior, while 44 (36.7%) of the respondents had adequate foot self-care behavior.

Hypotheses testing

Ho: There is no significant individual and composite association between age, gender, educational status and behavior of FSC among PWDM.

|

Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients (B) |

Std. Error |

Standardized Coefficients (Beta) |

t |

Sig. (p-value) |

|

|

(Constant) |

38.543 |

7.692 |

5.011 |

<0.0001 |

||

|

Age |

2.622 |

6.077 |

0.133 |

0.432 |

0.667 |

|

|

Gender |

-1.078 |

9.246 |

-0.018 |

-0.117 |

0.907 |

|

|

Educational Status |

-2.089 |

8.227 |

-0.086 |

-0.254 |

0.800 |

|

|

Note: Dependent Variable = FSC Behavior |

||||||

Table 7. Multivariate analysis between age, gender, educational status and foot self-care behavioramongPWDM

As shown in Table 7, multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict the association between age, gender and educational status and self-care behavior. Particularly, by ANOVA summary for the Regression Model, the resultant model was not significant, F (3, 119) = 0.97, p = 0.962, R2= 0.002. Table 7 revealed that the individual variables also had no significant association of age (t = 0.432, p = 0.667), gender (t = -0.117, p = 0.907) and educational status (t = -0.254, p = 0.800) with FSC behavior.

As shown in Table 8, multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the association between knowledge of FSC, efficacy and self-care behavior of people with diabetes. Particularly, by ANOVA summary for the Regression Model, the resultant model for foot self-care efficacy and FSC knowledge against self-care behavior was significant, F (2, 119) = 589.764, p<0.0001, R2= 0.910.

Table 8 revealed that individual variables had significant association FSC knowledge (t =8.252, p<0.0001) and FSC efficacy (t =3.610, p<0.0001) with FSC behavior.

|

Predictor |

Unstandardized Coefficients (B) |

Std. Error |

Standardized Coefficients (Beta) |

t |

Sig. (p-value) |

|

(Constant) |

-31.312 |

3.983 |

– |

-7.861 |

<0.0001 |

|

Foot Self-Care Knowledge |

6.023 |

0.730 |

0.672 |

8.252 |

<0.0001 |

|

Foot Self-Care Efficacy |

0.446 |

0.123 |

0.294 |

3.610 |

<0.0001 |

|

Note: Dependent Variable = Foot Self-Care Behavior. |

|||||

Table 8. Multivariate analysis between Foot Self-Care Knowledge, Foot Self-Care Efficacy and Foot Self-Care Behavior amongPWDM

DISCUSSION

The current investigation discovered that very few participants were older than 70. This result contradicts the age-based rate reported by Odusan, Amoran, and Salami [25], who observed that the elderly have a higher prevalence of diabetes than youngsters. Nonetheless, the present result is consistent with the CDC’s [26] assertion that the number of children, adolescents, and young adults developing DM is rising. The fact that many young people are leading improper lifestyles could help to explain this predicament. Some of these youths, who come from parents who are secure in terms of socioeconomic status yet reside in the city, lead unhealthy lives because they eat junk food and exercise infrequently. This scenario can make a good number of them to be diabetic. The study’s finding in concordance with previous research findings shows more females with diabetes, this agrees with Turan et al. [27] and Wazqar et al. [5] that more females are diagnosed with diabetes more than their male counterparts. Most of the respondents had higher education this is in agreement with Bekele [28] findings that higher educational status is one of the predictors of FSC practices. Majority were T2DM (53.8%) which corresponds with Sen et al. [29] and Wanja et al. [30], of which majority were diagnosed within the last 24 months.

The level of knowledge of PWDM on foot ulcer preventive self-care activities.

One of the main conclusions of this study was that the respondents’ level of FSC knowledge was low. Consequently, there is a need for skilled instruction on diabetes FSC and the creation of guidelines for PWDM to carry out FSC. This conclusion runs counter to prior research by Alshammari et al. [31], who discovered that around 282 (76.6%) of the patients in their Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, study had a thorough awareness of foot ulcers and diabetic foot. The literature, however, provides a wealth of evidence to support the reported position of low knowledge of FSC. Goie and Naidoo [12] and Adeyemi et al. [16] for example, agreed with Ogunlana [29] when she stated that individuals with diabetes mellitus in Sub-Saharan Africa have a limited understanding of the complications associated with their disease. As Africans, we rely heavily on the rule of thumb in many situations, particularly in times of emergency when managing diabetes calls for it. Except for the standard, frequently ineffectual recommendations obtained during hospital visits, there are very few proactive steps available for managing the difficulties associated with diabetes in such circumstances. Thus, the creation of an out-of-hospital care regimen becomes necessary.

The self-efficacy of PWDM to practice foot ulcer preventive activities

The discovery that the majority of those who participated had poor FSC Efficacy scores is another indication of the growing mortality and morbidity linked to diabetes and its complications. People lack the abilities, bravery, and self-assurance necessary to combat, control, and overcome DFU, a serious symptom that causes suffering and casualties for diabetics. The findings in this study deviated from the seemingly typical trend, even though Narmawan, Syahrul, and Erika [32] and Sharoni et al. [33] had previously demonstrated that the patients in their studies had high FSC efficacy. Additional published research that supports the inherent deficiencies in FSC efficacy or parallel variables among diabetics include Wazqar et al. [5], Khan et al. [9], Mekonen and Demssie [34], and Turan et al. [27]. These studies were founded on evidentiary viewpoints. It is interesting to know why the present result in this study—which isn’t generally praised in the literature—is what it is. However, the majority’s low FSC efficacy is not surprising in the slightest because, despite claims to the contrary, a population lacking in knowledge cannot assert that it has high self-efficacy—a concept that is far higher than knowledge and that no conventional education can ensure. In summary, while knowing is crucial for self-care, it might not necessarily translate into self-efficacy. This suggests that educational initiatives that just emphasize knowledge may not result in self-efficacy, and it is unwarranted to assume that a lack of knowledge will lead to a lack of efficacy or self-confidence. This means that, if self-efficacy had been high, the participants in this study would have had low moment foot self-care knowledge.

Foot self-care behavior of people with diabetes

A significant finding of this study indicated that a considerable number of individuals had insufficient foot self-care practices. This leads to the primary rationale of this study. Low levels of self-care behavior are thought to be the underlying cause of DFU. The present finding of low self-care behavior with respect to DFU emphasizes the earlier position of Ammar et al. [35] that foot ulcers and amputations are regrettably prevalent with poverty, improper sanitation and hygiene, and barefoot walking often connecting to worsen the adverse effects of diabetic foot damage. Hirpha, Tatiparthi, and Mulugeta’s [13] additional research, which observed that those with diabetes did not sufficiently self-inspect, wash their feet at least once a day, dry after washing, and moisturize the dry skin as they walked barefoot, in sandals or slippers, or in shoes without socks, supports the results under discussion. It is important to stress that the existing practice goes against the advice given by Armstrong et al. [36] and van Netten et al. [37], who provided factual evidence to support their recommendations regarding the importance of routine foot inspections for PWDM. The problem persists when the number of patients in need of health care services is not matched by the number of caregivers and health workers/educators currently in place. This documented anomaly is therefore not unrelated to the culture of unsanitary living, complacency, misinformation, and poor knowledge among some people.

The results demonstrated that foot self-care behavior was not predicted by age, gender, or educational attainment. While earlier research [33,32,20,38] suggested that specific age, gender, and educational level reinforce FSC behavior, the present investigation has documented the opposite for reasons that are closely related to the fact that care behavior is a personal matter, independent of known biases or socioeconomic inclinations.

The findings also highlight the importance of collaboration in attempts to instill the necessary skills and attitude to give the motivation needed for effective self-care behavior. Lastly, the significant individual and joint association of FSC knowledge and foot care self-efficacy with FSC behavior highlights the need for each of these factors to instill self-care behavior. In their research, Wendling and Beadle [39] showed that self-efficacy advancement is a successful nursing intervention for health promotion. Positive outcomes, such as better outcomes for people with diabetes mellitus, fewer admissions, and fewer ER visits, have been linked to this. Additionally, the study offered some limited understanding of the significance of the identified relationships. Support for the necessity of matching knowledge to practical skill training was given in 2016 by Sarkar et al. and Sharoni et al. [33], whose studies, respectively, demonstrated a major beneficial connection between self-efficacy and self-care practices among PWDM and an improvement in FSC behavior, foot care knowledge, foot care outcome expectation, and QoL (physical symptoms) after training.

CONCLUSION

Patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DM) frequently get DFU, and foot self-care (FSC) is a useful strategy to reduce this risk. But self-care is becoming more and more common because paid care services are expensive and there aren’t many caregivers accessible. With an emphasis on young individuals aged 21 to 30, the research sought to assess FSC behavior for DM patients. Participants in the study had poor scores on behavior, efficacy, and knowledge assessments. Age, gender, and educational attainment did not significantly correlate with foot self-care behavior.

It is necessary to invest in educational interventions to provide patients with the skills and knowledge necessary for good foot care practices. These initiatives shouldn’t, however, necessarily be classified according to factors like age, gender, or educational attainment. The results demonstrated a substantial correlation between efficacy and foot self-care behavior, indicating that increasing efficacy or FSC knowledge on its own might greatly enhance self-care behavior.

According to the study’s findings, 91.1% of the variance in foot self-care behavior could be explained by knowledge of FSC and efficacy, which had a substantial composite connection with foot self-care behavior. In order to expedite the practice of foot self-care, educators must impart information of foot self-care (FSC) and its efficacy in addition to the requisite technology, scientific skills, practices, and artistic qualities. For greatest benefit, this will assist DM patients in initiating, managing, and engaging in self-care practices.

Based on the findings and discussions presented in this study, several important recommendations are proposed. Healthcare providers should prioritize expanding and promoting diabetes education programs that not only enhance patients’ knowledge of foot self-care (FSC) but also strengthen self-efficacy by teaching practical skills and fostering confidence in patients’ ability to carry out these activities. Patients must also be educated on the importance of choosing appropriate footwear, with a strong emphasis on the benefits of well-fitting shoes and the risks of walking barefoot, both indoors and outdoors, as a preventive measure against foot complications. In addition to education, healthcare professionals and educators are encouraged to implement strategies that boost patients’ self-efficacy, such as goal-setting, individualized feedback, and supportive reinforcement that affirms their ability to manage self-care effectively.

Developing and distributing clear, concise self-care guidelines or protocols is essential, as is stressing the importance of regular foot examinations. Patients should be empowered to conduct daily foot checks and trained to identify signs such as cuts, blisters, or dryness that may require prompt attention. Furthermore, they should be cautioned against risky practices like using razor blades to remove corns and calluses and instead be encouraged to seek professional care for such concerns. Another important hygiene recommendation is to emphasize the necessity of changing socks regularly to maintain healthy foot conditions and prevent infections. These educational efforts should be institutionalized within healthcare policies at both national and facility levels, and embedded into healthcare training curricula for sustainable impact. Additional studies should be carried out to assess the effectiveness of foot care education, identify barriers to its implementation, and develop strategies to address these challenges.

Limitations and recommendations

The generalizability of the findings may be limited by factors such as sample size and study design, and future research should consider broadening the scope and incorporating multiple methodological approaches to enrich the validity of results. This study contributes to knowledge by showing that while knowledge is important, it alone is insufficient to improve patients’ foot self-care behavior unless it is reinforced by self-efficacy strategies and potentially other factors not examined in this research. It also presents evidence that differentiated learning based on age, gender, or education level may not be necessary for effective foot self-care training among patients. A key outcome of this study is the proposed knowledge-efficacy-behavior framework, which provides a conceptual basis for mastering diabetic foot self-care behavior.

In light of the study’s limitations and findings, further investigations are encouraged. Future researchers may consider integrating more independent variables—such as personal hygiene habits, coexisting health conditions, and access to healthcare services or information—into predictive models for foot self-care behavior. A quasi-experimental study design may also be employed to evaluate the effectiveness of targeted intervention packages on patients’ behavior. Additionally, new tools such as systematic observation instruments can be developed to complement the questionnaire method used in this study, offering a more comprehensive assessment of self-care practices.

Local Ethics Committee approval:

1. The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Ogun State Hospital Management Board with REF NO: SHA 52/VOL XII/116. Date of approval: August 23, 2023.

2. The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Federal Medical Center with REF NO: FMCA/470/HREC/01/2023/23NHREC/08/10-2015. Date of approval: June 19, 2023

Competing interests: None to declare.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Authors’ contribution

Oseni Rukayat: Conceptualized idea and conducted full research.

Emmanson Emmanson: Assisted with the research and manuscript preparation for publication

Kolawole Ifeoluwapo:Assisted with the design of questionnaire and conducting interviews with the selected nurses.

Adejumo Prisca: Was responsible for literature reviews.

Obilor Helen: performed data analysis and edited the manuscript for publication.

REFERENCES

- International Diabetes Federation (2022). Diabetes around the world in 2021. 10th edition. https://diabetesatlas.org/#:~:text=1%20in%208%20adults%20(206,caused%20by%20diabetes%20in%202021. Accessed 24/02/2023.

- Paulsamy, P., Ashraf, R., Alshahrani, S. H. et al. (2021). Social Support, Self-Care Behaviour and Self-Efficacy in Patient with Type 2 Diabetes during the COVID- 19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. National Library of Medicine. Healthcare (Basel). 9(11):1607. Doi:10.3390/healthcare9111607. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8622453/. Accessed 02/11/2023.

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention, (2023). Diabetes in Young People Is on the Rise. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/resources-publications/research-summaries/diabetes-young-people.html. Accessed 15/11/2023.

- World Health Organization, (2022). Diabetes. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1. Accessed 05/06/2022.

- Wazqar AA, Baatya MM, Lodhi FS, Khan AA. Assessment of knowledge and foot self-care practices among diabetes mellitus patients in a tertiary care centre in Makkah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional analytical study. Pan Afr Med J. 2021 Oct 29;40:123. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.123.30113. PMID: 36118942; PMCID: PMC9463747.

- Ugwu E, Adeleye O, Gezawa I, Okpe I, Enamino M, Ezeani I. Burden of diabetic foot ulcer in Nigeria: Current evidence from the multicenter evaluation of diabetic foot ulcer in Nigeria. World J Diabetes. 2019 Mar 15;10(3):200-211. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v10.i3.200. PMID: 30891155; PMCID: PMC6422858.

- Robles, R. B., Compean Ortiz, L. G., […] and Martinez, S. P. (2017). Knowledge and Practice of Diabetes Foot Care and Risk of Developing Foot Ulcers inMexico May Have Implications for Patients of Mexican Heritage Living in the US. SAGE Journals Vol 43, Issue 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721717706417. Accessed 28/03/2023.

- Oliver, T I. and Mutlouglu, M. (2022). Diabetic Foot Ulcers. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537328/.Accessed 24/07/2022.

- Khan, Y., M. Khan, M., & Raza Farooqui, M. (2017). Diabetic foot ulcers: a review of current management. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 5(11), 4683–4689. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20174916.

- Rahaman HS, Jyotsna VP, Sreenivas V, Krishnan A, Tandon N. Effectiveness of a Patient Education Module on Diabetic Foot Care in Outpatient Setting: An Open-label Randomized Controlled Study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jan-Feb;22(1):74-78. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_148_17. PMID: 29535941; PMCID: PMC5838916.

- Boulton, Andrew. (2021). Diabetic Foot Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina. 57. 97. 10.3390/medicina57020097.

- Goie TT, Naidoo M. (2016). Awareness of diabetic foot disease amongst patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending the chronic out-patients department at a regional hospital in Durban, South Africa. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 8(1), a1170. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1170. Accessed 07/07/2022.

- Hirpha, N., Tatiparthi, R., and Mulugeta, T. (2020). Diabetic Foot Self-Care Practices Among Adult Diabetic Patients: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S285929. Accessed 18/01/2023.

- Rural Health Information Hub (2020). Module 1: Health promotion and disease. Available at: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/1/introduction. Last access: 02/01/2023.

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N., Lozano-Madrid, M., Toledo, E., Corella, D., Salas-Salvadó, J., Cuenca-Royo, A., … & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2018). Type 2 diabetes and cognitive impairment in an older population with overweight or obesity and metabolic syndrome: baseline cross-sectional analysis of the PREDIMED-plus study. Scientific reports, 8(1), 16128 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33843-8.

- Adeyemi TM, Olatunji TL, Adetunji AE, Rehal S. Knowledge, Practice and Attitude towards Foot Ulcers and Foot Care among Adults Living with Diabetes in Tobago: A Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 29;18(15):8021. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158021. PMID: 34360314; PMCID: PMC8345419.

- Mekonen EG, Gebeyehu Demssie T. Preventive foot self-care practice and associated factors among diabetic patients attending the university of Gondar comprehensive specialized referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022 May 11;22(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-01044-0. PMID: 35546665; PMCID: PMC9097232.

- Tuha A, Getie Faris A, Andualem A, Ahmed Mohammed S. Knowledge and Practice on Diabetic Foot Self-Care and Associated Factors Among Diabetic Patients at Dessie Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia: Mixed Method. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021 Mar 17;14:1203-1214. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S300275. PMID: 33762837; PMCID: PMC7982550.

- Ogunlana MO, Govender P, Oyewole OO, Odole AC, Falola JL, Adesina OF, Akindipe JA. Qualitative exploration into reasons for delay in seeking medical help with diabetic foot problems. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2021 Dec;16(1):1945206. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2021.1945206. PMID: 34219610; PMCID: PMC8259813.

- Ojewale, L.Y., Okoye, E. A. and Ani, O. B. (2021). Diabetes Self-Efficacy and Associated Factors among People Living with Diabetes in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria. European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. Vol. 3 No. 6. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejmed.2021.3.6.1129.

- Lincoln, N., Jeffcoate, W., Ince, P., Smith, M. and Radford, K. (2007), Validation of a new measure of protective footcare behaviour: the Nottingham Assessment of Functional Footcare (NAFF). Pract Diab Int, 24: 207-211. https://doi.org/10.1002/pdi.1099

- Sloan HL. Developing and testing of the Foot Care Confidence Scale. J Nurs Meas. 2002 Winter;10(3):207-18. doi: 10.1891/jnum.10.3.207.52564. PMID: 12885146

- Ayre, C., & Scally, A. J. (2014). Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 47(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175613513808

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel psychology, 28(4).

- Odusan, O., Amoran, O. E., & Salami, O.E. (2017). Prevalence and pattern of diabetic foot ulcers among adults with diabetes in a secondary health care facility in Lagos, Nigeria. Anals of health research:3(2). https://www.annalsofhealthresearch.com/index.php/ahr/article/view/70. Accessed 28/03/2023

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention, (2023). Diabetes in Young People Is on the Rise.https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/resources-publications/research-summaries/diabetes-young-people.html. Accessed 15/11/2023

- Turan, E., Onalan, R., Iscimen, N. C., Ozan, Z. T., Yildirim, T., & Aral, Y. (2020). Foot Self-Care Behavior in Patients with Diabetes. J Soc Health Diab:2020;8:13-17 http://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1716812

- Bekele, F., Berhanu, D., Sefera, B., & Babu, Y. (2021). Diabetic foot self-care practices and its predictors among chronic diabetic mellitus patients of Southwestern Ethiopia hospitals: a cross-sectional study. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100489. Accessed 25/03/2023.

- Şen HM, Şen H, Aşık M, Özkan A, Binnetoglu E, Erbağ G, Karaman HI. The importance of education in diabetic foot care of patients with diabetic neuropathy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2015 Mar;123(3):178-81. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1389981. Epub 2014 Oct 14. PMID: 25314654.

- Wanja L, Mwenda C, Mbugua R, Njau S. (2019). Determinants of foot self-care practices among diabetic patients attending diabetic clinic at a referral hospital, Meru County – Kenya. Int J Sci Res Public. 9(10):p9461. Doi:10.29322/ijsrp.9.10.2019.p9461. Accessed 18/01/2023.

- Alshammari ZJ, Alsaid LA, Parameaswari PJ, Alzahrani AA. Attitude and knowledge about foot care among diabetic patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019 Jun;8(6):2089-2094. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_248_19. PMID: 31334185; PMCID: PMC6618215.

- Narmawan, Narmawan & Syahrul, Syahrul & Erika, Kadek Ayu. (2018). THE BEHAVIOR OF FOOT CARE IN PATIENTS WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS: APPLYING THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR. Public Health of Indonesia. 4. 129-137. 10.36685/phi.v4i3.209.

- Sharoni SKA, Abdul Rahman H, Minhat HS, Shariff Ghazali S, Azman Ong MH. A self-efficacy education programme on foot self-care behaviour among older patients with diabetes in a public long-term care institution, Malaysia: a Quasi-experimental Pilot Study. BMJ Open. 2017 Jun 8;7(6):e014393. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014393. PMID: 28600363; PMCID: PMC5623401.

- Mekonen EG, Gebeyehu Demssie T. Preventive foot self-care practice and associated factors among diabetic patients attending the university of Gondar comprehensive specialized referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022 May 11;22(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-01044-0. PMID: 35546665; PMCID: PMC9097232.

- Ammar I, Jude E, Katia Langton FR, et al. (2017). International Diabetes Federation (IDF): Clinical Practice Recommendation on the Diabetic Foot: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. Vol. 127; 2017. Doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.04.013. Accessed 18/01/2023.

- Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 15;376(24):2367-2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1615439. PMID: 28614678.

- van Netten JJ, Price PE, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Jubiz Y, Bus SA; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Prevention of foot ulcers in the at-risk patient with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016 Jan;32 Suppl 1:84-98. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2701. PMID: 26340966.

- Ong JJ, Azmil SS, Kang CS, Lim SF, Ooi GC, Patel A, Mawardi M. Foot care knowledge and self-care practices among diabetic patients in Penang: A primary care study. Med J Malaysia. 2022 Mar;77(2):224-231. PMID: 35338631.

- Wendling S, Beadle V. The relationship between self-efficacy and diabetic foot self-care. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015 Jan 27;2(1):37-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2015.01.001. PMID: 29159107; PMCID: PMC5685009.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.